How fraud keeps growing

On the rise of first party fraud

Fraudster (noun) chiefly British English

A person who commits fraud

The word fraudster first appeared in 1975 in the Financial Times (London).

Post Synopsis: Fraud in online payments is a big problem. It costs businesses and card issuers billions of dollars a year. The biggest problem in fraud is now so-called first-party fraud - this is user-instigated fraud. Yet most of us don't think we commit fraud, at least knowingly so. Read on to find out how fraud is changing, and we all may be part of the issue.

The Fraud Problem

Fraud sounds serious, and it is. The maximum sentence in the UK for successful fraud prosecution is ten years in prison. But a sentence of this length - or anywhere near it - only applies in cases where the fraud involves a high value. For a sentence of ten years, the value of fraud would need to be in the millions of pounds.

In online payments, the average value of a single fraud case is in the low hundreds of dollars. Professional fraudsters work in such a way that cases can rarely be traced back to one person or one criminal organisation. Organisations can be hacked and card details stolen en masse, especially if a retailer doesn't store card data securely. However, innovation is helping. Technology such as card tokenisation means it's now easier than ever for retailers to secure customer information. If card information is tokenised and stored securely, it's much less useful to fraudsters even if they manage to hack their way in and get to the data.

That said, fraud is ever-evolving. Last month, The Guardian reported on one of the largest online scams discovered so far. Hundreds of thousands of consumers were scammed into handing over personal information - including card numbers - by a network of fake e-commerce stores:

The first fake shops in the network appear to have been created in 2015. More than 1m “orders” have been processed in the past three years alone, according to analysis of the data. Not all payments were successfully processed, but analysis suggests the group may have attempted to take as much as €50m (£43m) over the period. Many shops have been abandoned, but a third of them – more than 22,500 – are still live.

So far, an estimated 800,000 people, almost all of them in Europe and the US, have shared email addresses, with 476,000 of them having shared debit and credit card details, including their three-digit security number. All of them also handed over their names, phone numbers, email and postal addresses to the network.

The impact of this case will reverberate for some time, and it shows the many levels on which fraud can take place. Users who provided their card details to these fake stores may now see transactions they don't recognise. The impact will be felt by the card issuers, who will usually be liable to refund their cardholders.

In Europe, extra security measures such as two-factor authentication are mandated. With two-factor authentication in place, it's now more challenging to use stolen card details. To complete a transaction, a pre-registered mobile phone number - or another means of authentication - is needed.

Such measures are not in place in much of the world. Criminal organisations know the weak spots. They know where they can spend their potential gains most effectively. Once card details and other personal information are taken, they can be used anywhere in the world. The only barrier is the fraud controls of the cardholder's issuing bank. But if criminals steal 400,000+ card numbers, they'll try many of them, knowing that many will work and many will not.

The research firm Juniper has estimated that businesses lost $38bn to fraud in 2023, and this will rise to £91bn by 2028. Other jurisdictions may follow in Europe's footsteps and introduce extra authentication measures to reduce fraud. But payments can't be totally free from fraud, especially as fraud can even originate from users themselves.

Fraud’s Biggest Problem?

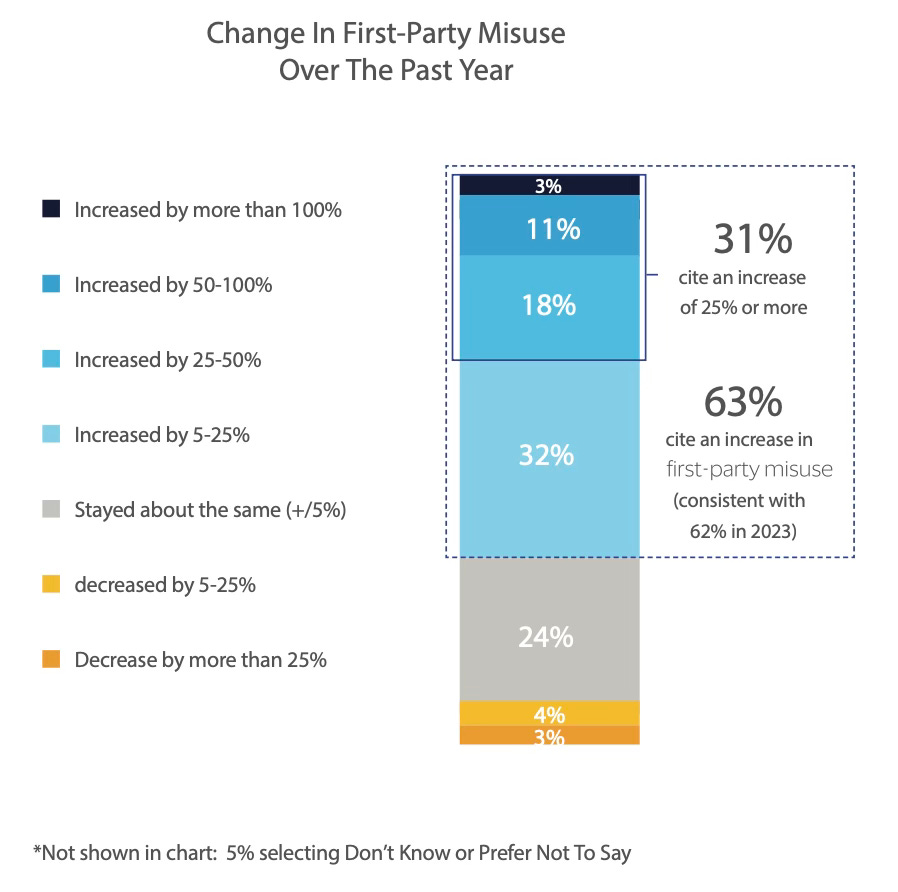

Merchant Risk Council (MRC) is an organisation that describes itself as "a global non-profit membership association for payments and fraud prevention professionals". At MRC's recent event, the one thing that struck me more than anything else was the level of discussion on what's known as first-party fraud.

Typically, when we think of fraud, what comes to mind is getting hacked and our stolen card details being used to buy a product we never see. Getting hacked and our card details used without our permission is third-party fraud. First-party fraud involves a user knowingly buying goods but using deception for monetary gain. Sometimes, rather than the term first-party fraud, the term first-party misuse is used. This term may sound softer, but the impact is the same.

In the world of payments, friendly fraud is a term often only used for cases in which a user initiates a dispute with their bank. There can be clear cases, such as a user receiving the product they ordered from an e-commerce retailer but claiming they did not. (Such cases are not always easy to prove. These days, some delivery companies take a photo of a package outside the door of the home they've delivered to. This is to confirm that someone actually delivered the product.) If the value of goods is below a certain level, then a retailer may opt to refund a user rather than defend a case. This happens because the cost of defending a chargeback in terms of fees and admin may be more than just refunding the client.

On other occasions, first-party fraud, or first-party misuse, is a term used to encapsulate something broader than just a formal dispute. In line with the definition of fraud as "a deception which results in financial gain", activities such as refund and voucher abuse can cause significant business challenges.

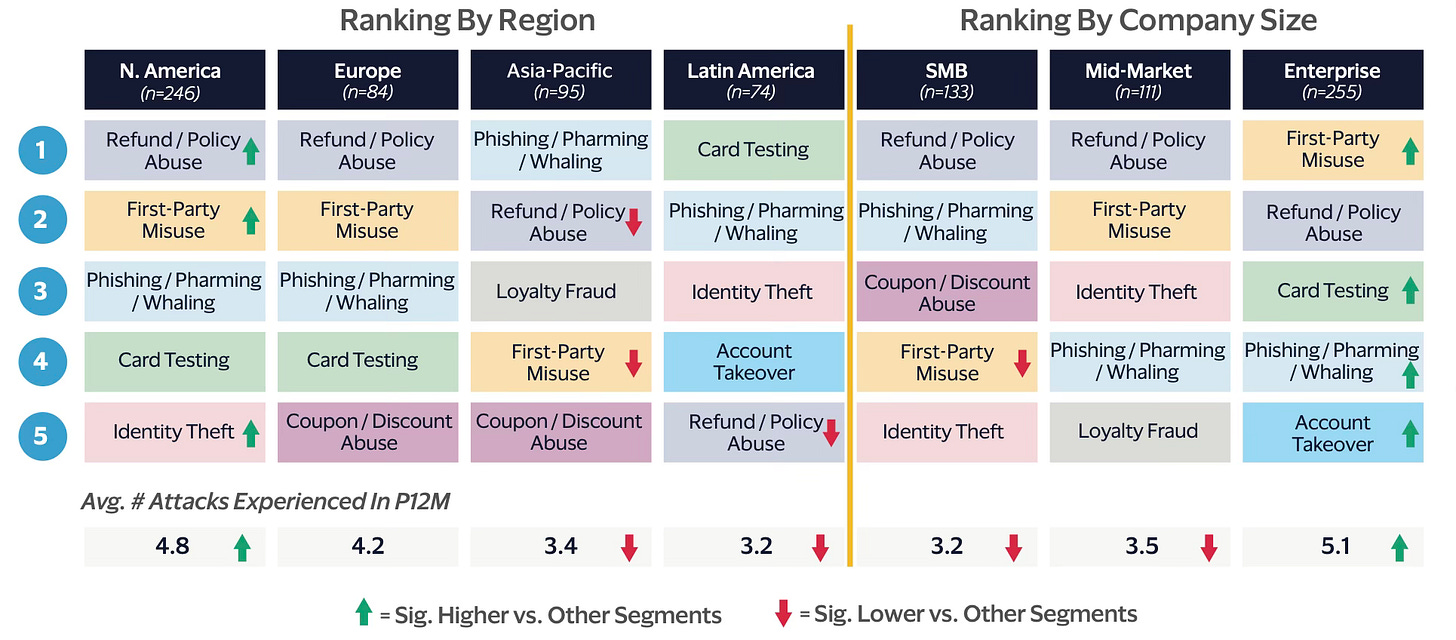

From a recent MRC report, the graphic below separates the categories First Party Misuse, Refund / Policy Abuse, and Coupon / Discount Abuse. I consider all these to be examples of general First-Party Fraud. Even if they don't all result in a formal dispute, they are all examples of a consumer benefitting from activities to the detriment of the retailer. That said, these days, the line between what's seen as fraudulent or not is becoming somewhat blurred in the minds of consumers. When I was at the MRC event, some examples were discussed and I hadn't previously thought of them as fraud per se.

Let's review some examples of first-party misuse, which are becoming more common. Would you consider these cases to be fraud?

Voucher Abuse. Many e-commerce stores offer a 10% discount code for the first completed order. This is intended to be used once per user only. Have you ever used a discount code a second time by using a second email address? Or asked your wife, husband, or other family member to sign up and order on your behalf? On the one hand, this may bring in additional sales that the business may not have otherwise received. However, the discount code is intended for one user making only their first purchase.

Refund Abuse. I'm sure we've all heard of this scenario: a product is ordered, used once or twice, and returned within the 14-day returns window. The consumer gets the benefit of the product for a short time period and gets a full refund. Of course, many countries have Consumer Rights legislation, meaning a product can be returned legitimately for various reasons. But refund abuse is when a user knowingly orders a product with the view of sending it back within the returns window. And never having the intention to keep the product long-term. In addition to losing the revenue of the sale itself, returns can cost up to 60% of an item's original sale price. So, this type of fraud can be particularly costly for the retailer.

Basket Size Abuse. Some e-commerce retailers only offer free delivery if the total purchase exceeds a certain value. Users may add an item to their basket to take it over the free delivery level. But with the intention of returning the product that took their basket size over the free delivery limit. Or rather than just free delivery, perhaps there's a discount triggered by a minimum basket size. On the one hand, consumers may say that minimum order values - for free delivery - are increasing the prospect of such behaviours. Yet, on the other hand, retailers have a cost of delivery that they need to cover, and free delivery may impact the profitability of each order.

Changes in payment habits have potentially influenced how consumers think of fraud. For example, some businesses offering Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL) actually tell consumers that it's OK to order multiple sizes. Then try them on at home, and then send back those that don't fit. In some cases, retailers don't see an issue with this approach. Combined with BNPL, the ability to try items on at home and then keep the best fit can increase overall basket size - even post-return. Yet such behaviours can have significant consequences if the merchant has not built this into their business model. For non-BNPL purchases this approach, of try many and send back most may be outside of the terms and conditions of the sale.

A Different Point Of View

I started this post by asking, "are you a fraudster?" to question whether we consider certain behaviours to be a fraud. The term fraud carries heavy connotations, so I expected that few who commit first party fraud actually feel they are committing a crime. But this isn't so clear. Data from Cifas, a not-for-profit organisation working to reduce and prevent fraud, has found 1 in 8 adults in the UK has admitted to committing fraud in the past 12 months. A report on the topic of first-party fraud, by fraud prevention company Ravelin, adds some further insight on how consumers view fraud:

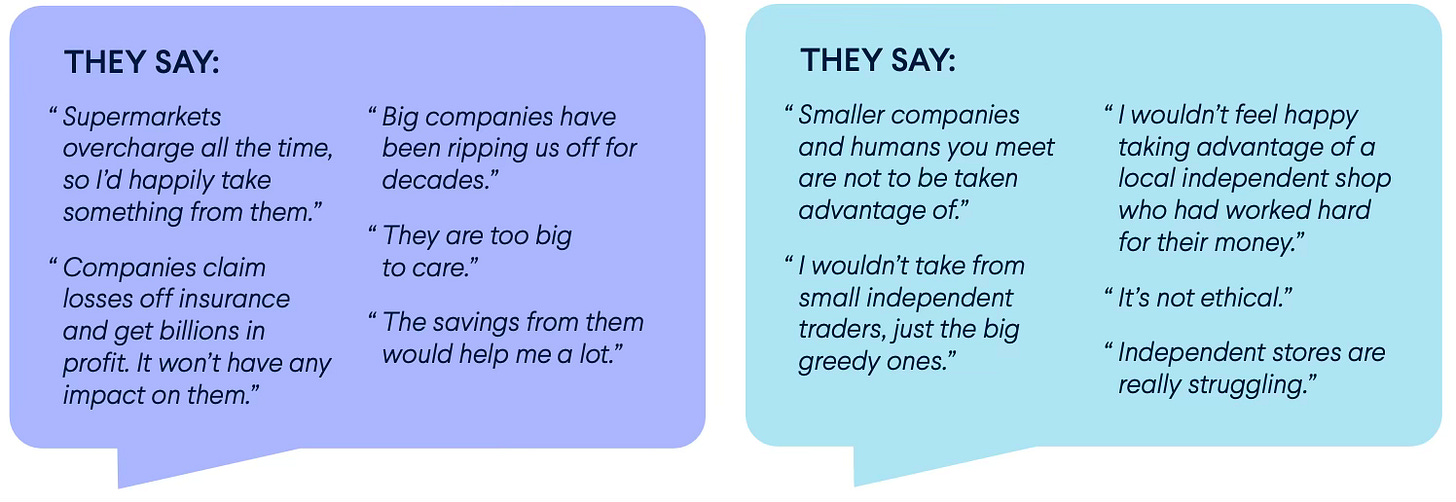

Whether they think it’s criminal or not, consumer fraudsters want to absolve themselves of the blame. Not only do they see these activities as victimless crimes where no one gets hurt (according to 25% of all respondents), but they say that brands make it easy to rip them off (22%).

The same report noted that almost half of the respondents believe that the responsibility of stopping fraud rests with companies themselves, rather than with the fraudster. This is in line with the view that it's fine to take advantage of flaws in returns policies and that the onus is on businesses to ensure that any misuse isn't possible. In reality I doubt consumers are checking the detail of refund and returns policies, instead this is an after-the-fact justification of any fraudulent activities.

Some of these responses may lead us to question: if first-party fraud is growing, then does that mean people are becoming more dishonest? It's not possible to say. But as more payments are made online the opportunities to bend the rules and take advantage increases. It's certain to say for those who work in the payments industry, there will always be space for new products and solutions to help crack down on first-party fraud. Retailers will need to keep learning and improving their processes, and some consumers will always find ways to test the boundaries of what's regarded as fraud.

This was an interesting read, thank you!