Crossing the chasm with payments (part 1)

What can payments companies learn from tech successes and failures?

Some companies and some technologies never make it big. Especially, but not exclusively in B2B, products often fail because they struggle to cross the chasm.

Crossing the chasm is hard.

Companies find it tough to go from having a product or service with a small number of early adopters to one embraced by the majority of buyers in a market.

You’ve likely seen or heard this concept before. It’s an idea most relevant to discontinuous innovation. In other words, big epoch-defining changes in technology.

Some examples of discontinuous innovation include:

Dumbphone → Smartphone

Physical mail → Email

Cable TV → Streaming

In all cases, successful examples of discontinuous innovation involve disruption, creating new value for users, and the potential to leapfrog competitors.

Successful discontinuous innovation often creates a brand new category, fulfilling customers’ immediate needs but also unlocking possibilities they hadn’t yet imagined.

How not to cross the chasm

Remember the reaction of Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer when the iPhone was first introduced? He laughed, thinking that no one would ever buy a $500 phone. However, events unfolded in a way that Ballmer likely did not expect.

In September 2013, Microsoft announced that it would acquire Nokia for $7.2 billion. This move had been on the cards for a while. Steven Elop had joined Nokia from Microsoft in 2010 as their new CEO and, in 2011, made the fateful decision to stop using Nokia’s proprietary Symbian platform.

Rather than adopting the fast-growing Android platform, Nokia opted for the Windows Phone operating system as its Symbian replacement. At the same time, Nokia and Microsoft entered a strategic partnership. This partnership arrangement lasted a few years until Microsoft’s acquisition of Nokia was completed in April 2014. Yet in July 2015, just over a year later, Microsoft announced a $7.6 billion write-off of its Nokia acquisition.

By the end of the decade Microsoft had left the mobile phone business entirely.

When writing this, I had a flashback to Autumn 2013. I was working for a company that gave me a Windows Phone for corporate use. It was truly dreadful to use, and it seems like others felt the same. Windows Phone as an operating system never garnered more than 3.2% of the smartphone market share. The limited success was mainly due to sales to corporate clients.

Meanwhile, since 2014, Apple has made more than $1.65 trillion worth of iPhone sales. The iPhone successfully crossed the chasm. Visionaries loved it, and pragmatists soon followed. The price was not the issue that Steve Ballmer expected; the iPhone sold out at launch, as it did at subsequent launches.

The iPhone’s success started with the consumer market, and a large share of the consumers who opted to buy the iPhone were already familiar with the iPod. Apple’s Press Release at the time of the announcement of the iPhone even played on its similarity with the iPod, declaring it to be “a widescreen iPod”, albeit one with email, Google Maps, a full web browser, and other appealing functionality.

Over the years, Apple gradually added functionality prized by large enterprises, enabling it to win market share on the business side as well as on the consumer side.

The origin of an idea

The concept of crossing the chasm was first coined by Geoffrey Moore in the early 1990s and has been a useful reference point ever since. It looks at why products or services succeed in a way that goes beyond simplistic technical or cost reasons, as having more features or being cheaper are not themselves guarantees of success.

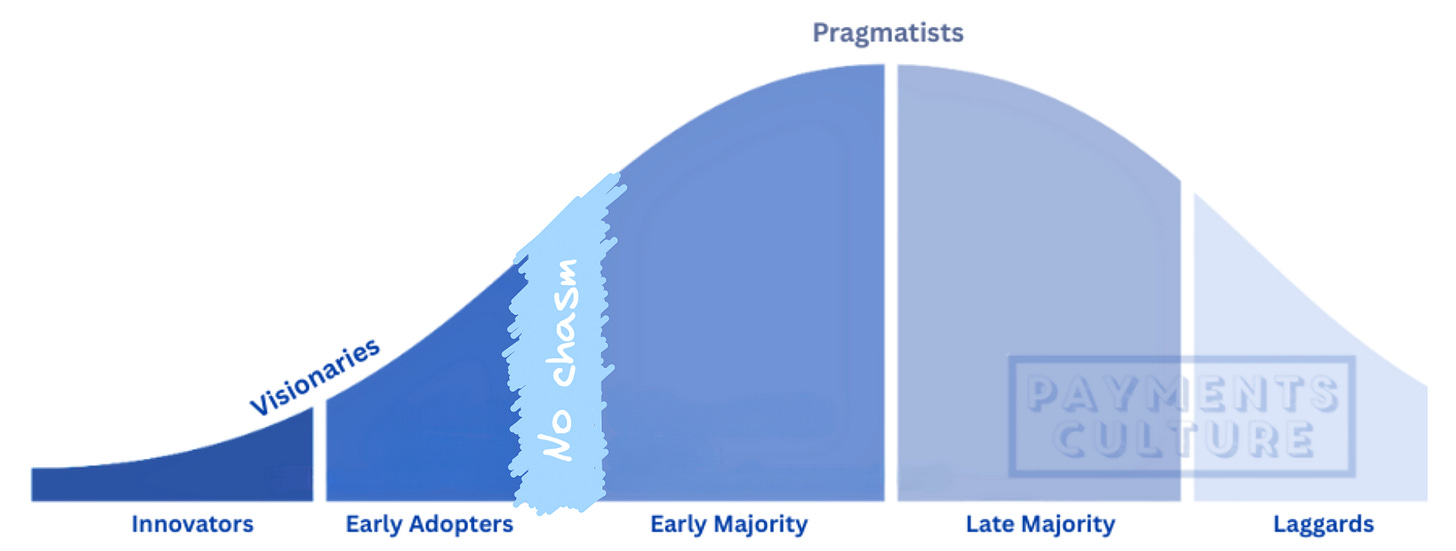

In his book, unsurprisingly called Crossing the Chasm, Moore broke down technology adopters into five groups, two of which sit before the chasm, and three of which reside after the chasm. The two before the chasm are:

innovators (2.5%)

early adopters (13.5%)

The three after the chasm are:

early majority (34%)

late majority (34%)

laggards (16%)

The percentages represent the distribution of new technology adopters.

It wasn’t Moore who derived these percentages; they came from Everett Rogers, a researcher best known for his book Diffusion of Innovations. Rogers’ work was influenced by a long-term study of farmers in Iowa, looking at their willingness to adopt new technology in the time period from 1928 to 1941. The study focused on what influenced farmers to adopt innovations such as hybrid seed corn.

The topic of the original study was a world away from today’s tech innovation.

Hence, Moore observed that when looking at tech, an additional nuance was needed.

He identified a gap — a chasm— between the early adopters, who were happy to try new technology even if it was not fully developed, and the early majority, who preferred to buy a comprehensive, tried-and-tested solution.

Many technology products fail to transition from the visionaries and early adopters, who are keen to try new things, to the mass market, who are more risk averse. Buyers on the other side of the chasm want products with a strong ecosystem and credible references to back up what a new product may claim to do.

Anyone remember the Apple Vision Pro? As much as I love Apple and VR/AR, I don’t think this product is even near to the chasm at this point in time. The price is too high for mass adoption and third-party app support has been poor.

Specifics matter

The key thing to remember when looking at crossing the chasm, is that it’s a framework to understand why a specific company’s specific product or service succeeds in a specific market segment in a specific geography. All of these elements are crucial.

See below from Moore’s book:

Cross the chasm by targeting a very specific niche market where you can dominate from the outset, drive your competitors out of that market niche, and then use it as a broader base for operations.

In some cases, companies cross the chasm in one market, but not others. A case in point: Facebook initially struggled in Japan. Back in 2011, the New York Times reported that:

Facebook users in Japan number fewer than two million, or less than 2 percent of the country’s online population. That is in sharp contrast to the United States, where 60 percent of Internet users are on Facebook.

Facebook’s policy of requiring users to use their actual names didn’t work well in a society with a preference for anonymity. Users in Japan liked using social media as a form of escapism, and not to replicate real life. Additionally, Facebook didn’t take the required time or effort to localise its product for the Japanese market, which put users off. Facebook eventually found its niche in Japan as a B2B marketing and networking tool, which is quite different from how the platform is used in most other markets.

Facebook should have established that market entry in Japan would take considerable nous, and it couldn’t just copy what had worked in the US. B2B would have been a better entry point in Japan rather than going straight for the mass consumer market.

Companies shouldn’t assume that their solution can work in one market the same as in another. Regulation, culture, technical and historical factors can all play a part in what succeeds where. This can be seen in payments, where different products succeed in some markets and not others, for example:

In the US, Pay by Bank is still stuck with the early adopters. There’s multiple payment rails, and not all banks are connected to the same rail(s), which adds complexity. In contrast, in Brazil, real-time payments via PIX are the norm, to the extent that you can even say it’s now the default payment option of choice.

In India QR code payments are common due to the ubiquitous nature of UPI (Unified Payments Interface). UPI is free for low-value transactions and easily available on all devices. In contrast, selling QR code payments as a solution is difficult in the UK as everyone knows and uses contactless card payments.

In China everyone uses WeChat Pay and Alipay. Card payments never took off. The ecosystem around mobile payments and superapps flourished so quickly that cards were not needed. In contrast, Australia’s highly concentrated banking sector helped accelerate a fast rollout of contactless card payments, which are now entrenched.

In these examples, you can see how the same technology can be pre-chasm in some markets while being firmly mainstream in another. Crossing the chasm with a particular product can be hard due to the regulatory or business environment. In some cases these challenges can be overcome, but doing so requires a tailored approach which reflects different expectations on each side of the chasm.

How visionaries and pragmatists differ

In Moore’s view there’s a discontinuity between early adopters and the mass market.

Taking a minimum viable product (MVP) to market that succeeds with visionaries is quite different to the whole product solution that can appeal to pragmatists. Many companies fail with new products as they try to sell an MVP solution to pragmatist buyers (who don’t want something that seems half-finished). Likewise, if you’re selling to visionaries, who sit before the chasm, there needs to be an almost revolutionary differentiator to shake things up and get them interested.

As Moore notes in his book:

Visionaries fail to acknowledge the importance of existing product infrastructure. Visionaries are building systems from the ground up. They are incarnating their vision. They do not expect to find components for these systems lying around. They do not expect standards to have been established— indeed, they are planning to set new standards.

Crossing the chasm is not the same as a typical market entry or go-to-market strategy. Traditionally companies will look at the whole market opportunity, whereas the approach here is based on building dominance in a niche and then moving into adjacent areas. The key is to consciously understand, and to reference the different psychology of selling to visionaries (pre-chasm) and to pragmatists (post-chasm).

Before the chasm - We believe what you believe!

After the chasm - We need what you have!

As a baseline companies should consider the following as a starting point:

Target a specific vertical with a solution which solves a specific problem for the specific customer segment. A lower price than the competition isn’t enough, nor is more of the same of what others are doing. It has to be a pressing problem that you can fix and then capture the market in that segment.

Consider the whole customer journey. What part do you play? And is it enough? Successful payment solutions require onboarding, reporting, reconciliation, and other factors. To cross the chasm, do you need to partner with others to offer a solution wider than your core competency? (not uncommon in payments)

Define your success metrics. Focus on the metrics in your segment that’ll make your customers’ lives easier. One example is BNPL, which was shown to increase average basket size. Therefore even if the cost of BNPL is more than that of card payments, offering BNPL still makes sense for many retailers due to the upside.

As products succeed with early adopters and begin to mature, companies may be able to take more of their solution in-house rather than relying so much on third parties. Additionally, it can be beneficial to show a broader range of success metrics than those initially focused on. Pragmatists will welcome this maturity, but this group values traction, especially amongst customers like themselves.

In part two next week, I’ll look at case studies of payments companies that successfully developed their beachhead, and moved from a product loved by visionaries to one embraced by the mass market. I’ll cover companies like Stripe, Square, and Toast, and explore what they got right in crossing the chasm.

Geoffrey Moore was on a recent edition of Lenny’s Podcast, which is well worth a listen.

If you enjoyed reading this post, you can connect with me on LinkedIn, X, and BlueSky.

The concept of a chasm is sometimes helpful, but a common misunderstanding is that once you cross "the chasm," success is guaranteed. But that is a misconception. BEFORE early adopters validate your product, and throughout the mainstream market, success requires continuous adaptation. We have discovered there are actually 14 transition points (or chasms) on the adoption curve that require us to update our product offering and/or delivery mechanisms, and all of the things that deliver value to the customer. And we believe that changing the value we deliver is NOT a one-time thing. There must be constant "value reinvention." And that makes us efficient and effective across the entire lifecycle of market adoption. This is the model we follow: https://www.hightechstrategies.com/15-stages-of-value-creation/ This framework was authored by Warren Schirtzinger, who (coincidentally) is the original creator of the chasm concept before the book caused so many people to ignore long-term growth.

Hi Matt,

Nice job on the article.