How fintech can still help the planet

Despite ESG losing favour, sustainability schemes offer real world change, and payment tech can play a role too

I first wrote about sustainability in payments back in 2023.

As I return to the topic, it’s worth exploring the recent backlash against ESG, and how voluntary schemes such as 1% for the Planet and B Corp are growing in importance.

Fintech by default makes business more sustainable, think of neobanks that don’t need branches, or taking payments on an iPhone rather than a card machine.

Meanwhile Stripe offers users the ability to divert a percentage of sales to Stripe Climate as an easy way for users to do a little something to help the planet.

ESG soared, then flopped

2021 was the year of peak ESG. That year, a record $649 billion flowed into ESG-related investment funds. Larry Fink, the CEO of Blackrock, an Asset Manager, declared that “climate risk is investment risk”, and regulators made ESG disclosures a priority.

But the tide soon turned. 2022 saw net inflows of just $157.3 billion, down 75% from the prior year. 2023 and 2024 saw net outflows, particularly in the US. ESG wasn’t the pull that it once was. The trend for sustainable investment had stuttered.

Before ESG, there was Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), a much looser concept. Think of companies giving the staff a day off to do charity work, or having a bake sale to collect money for those less fortunate. CSD was about companies giving back to society and not measured by financial metrics.

ESG was something different. Initially, something specific to the investment world, Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG), became a useful framework for analysing companies more widely than traditional financial metrics, and it gave investors a broader lens through which to assess risk.

Examples of how the categories are applied in the original framework include:

Climate risk exposure - focused initially on things such as how weather events could disrupt company operations. Over time, this evolved to include companies’ plans to reduce their own carbon emissions. (Environmental)

Supply chain risks - labour conditions in distant markets where oversight is difficult can lead to significant reputational damage. One example that exemplifies this was the Rana Plaza disaster in Dhaka, Bangladesh, in 2013. (Social)

The factory roof collapsed, killing 1,134 workers, in a tragedy which was a wake-up call for the fast-fashion industry.

Since the disaster, retailers, such as Primark, have put major efforts into improving conditions on the ground.

Primark released an update 10 years after the tragedy detailing their work to support the victims’ families.

Executive compensation - ensuring management pay structures incentivise long-term performance, align with company goals, and maintain board independence. (Governance)

Originally, these factors were set up by investment analysts to examine material financial risks outside of standard corporate metrics. But over time, ESG evolved. It expanded to become a catch-all term for a wide variety of social causes, values, and political issues. Companies are moving away from the term ESG, and there has been a clear backlash, especially in the US.

Things quickly changed

The above example of climate risk exposure is a case in point. Climate risk went from a risk assessed in the supply chain, such as the risk of extreme weather events, to how a company could reduce its own carbon footprint. Many advocates would say these are inherently linked (carbon emissions do affect weather patterns), but the emphasis had fundamentally shifted. ESG went from being an investment risk analysis tool to a broader set of norms, standards and expectations that corporations were held to.

Now the mood is different. Firms are moving away from using the term ESG. Chuka Umunna, JP Morgan’s head of ESG for EMEA, despite his job title, said that:

There’s been a move towards using the term sustainability in the US over ESG just because it has become quite a politically loaded phrase. Whereas in Europe, I think the two terms are used interchangeably.

In today’s political environment, sustainability feels less politically charged than ESG.

DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion) became one of the most politically charged aspects of ESG. Even companies long seen as progressive regarding ESG issues, such as Google, have pulled back on hiring targets designed to increase representation from minority and unrepresented groups. Similar retreats are happening across Silicon Valley.

The backlash has even reached the courts. A Texas-led lawsuit alleges that major investment firms used ESG goals to engage in anticompetitive practices. From the Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) filing:

The case, led by Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, alleges that BlackRock, State Street, and Vanguard engaged in an anticompetitive conspiracy to drive down coal production as part of an industry-wide “Net Zero” initiative to further anti-coal Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) goals. BlackRock, State Street, and Vanguard allegedly exercised their influence as shareholders in competing coal companies to push them to reduce industrywide coal output. The multistate lawsuit alleges that these actions, along with the unlawful sharing of competitively sensitive information and other allegations, increased coal prices and forced American consumers to pay more for energy as part of an unlawful left-wing ideological scheme.

Despite the backlash, trillions in assets remain in ESG-related funds (now increasingly called sustainable funds). At the end of 2024, sustainable funds represented 6.8% of total Assets Under Management (AUM). Even amid changing political winds, there’s still significant interest, especially from European investors, where mandates to invest in sustainability-focused companies remain strong.

From ESG to Payments

Back in May 2023, prior to the ESG backlash kicking off, I took a look at how payments can help save the planet, noting some of the payment technologies making payments more sustainable. In the post, I noted how technology such as SoftPOS and QR code payments could lessen the environmental footprint for businesses. On the consumer side, technology, such as the growing use of virtual cards, can help consumers reduce their carbon footprint.

You may be thinking, how does using a virtual card help the environment?

Well, it’s been estimated that a standard plastic bank card has the following environmental impact:

60g CO2 coming from card body material

50g coming from manufacturing.

40g coming from other areas such as transport and packaging

The total 150g CO2eq (carbon dioxide equivalent) equates to the environmental impact of five plastic carrier bags. Therefore, by using a virtual card and never requesting a physical card, consumers can reduce their carbon footprint.

Some fintechs, such as Revolut, provide a virtual card by default, and asking for a physical card is the user’s choice. Apple Card in the US was virtual card first. UK credit card start-up Yonder allows paid users to request a physical card, but free users need to pay for one. With Apple Pay so common these days, the need for a physical card is diminishing, although a debit card is still needed to get cash from an ATM.

For those who want a physical debit card with eco credentials, Wise has the best option. Wise offers a biodegradable debit card, which is available upon request in-app. Monzo and Triodos Bank offer cards made from recycled PVC, which is the next best thing on the market right now. This trend towards sustainable cards is likely to continue. Card manufacturers are offering new innovative solutions, and users are more likely than ever to pay a bit extra to get a card which has sustainable credentials.

The challenge of E-waste

When I wrote How payments can help save the planet, I was working for a company in the SoftPOS space, which partly inspired my writing. SoftPOS is the technology that can turn a standard mobile phone or tablet into a payment terminal by utilising the NFC chip on the device to accept contactless payments. You may be wondering how does this help the environment, well quite simply, with SoftPOS a small business owner doesn’t need to purchase a card machine to accept payments, which means less electronic waste.

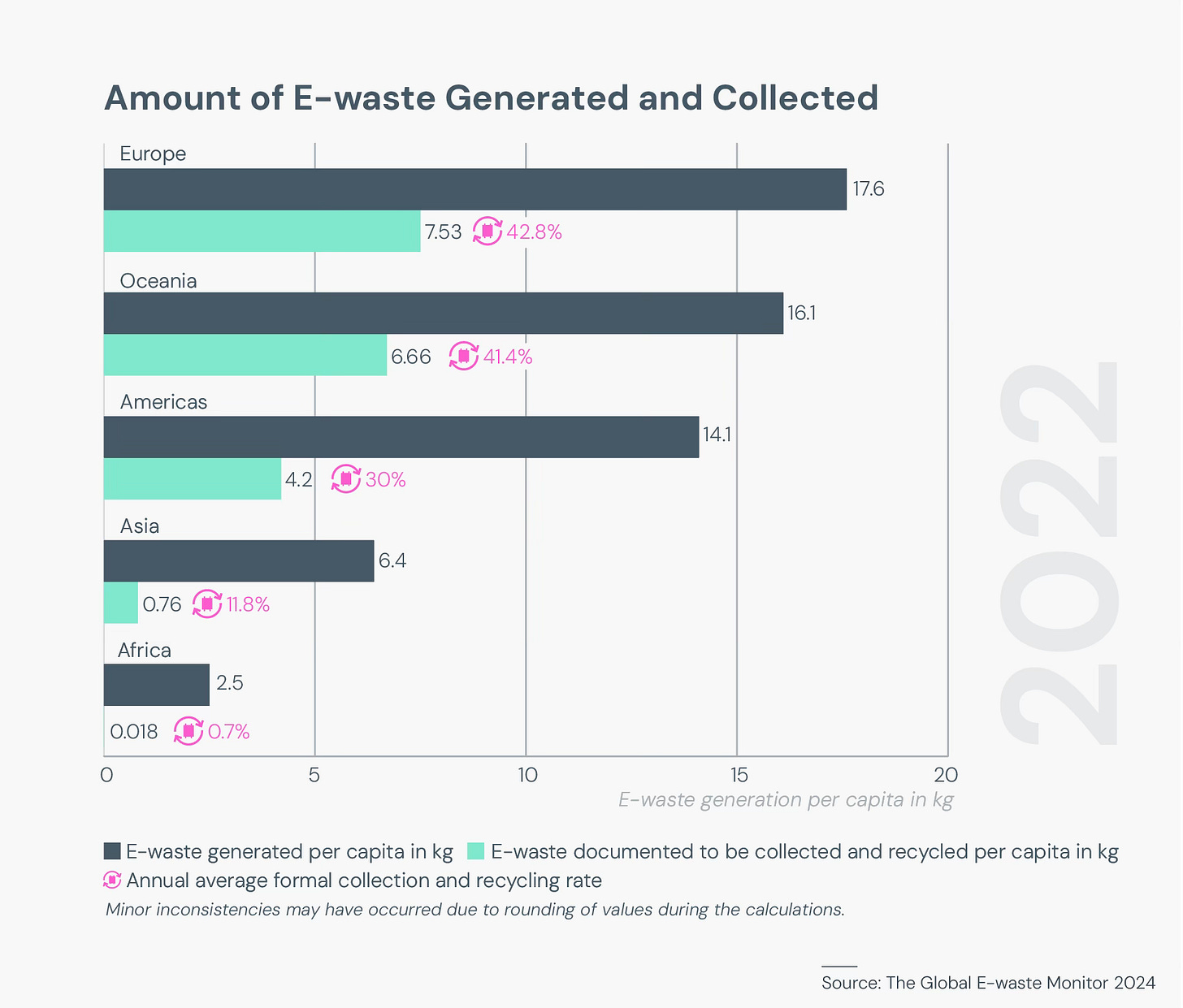

Back in 2023, I cited the UN’s Global E-waste Monitor (GEM) report, which previously estimated that e-waste would reach 74.7 million tonnes by 2030. The report was updated at the end of 2024, and the numbers are now predicted to be worse than first anticipated:

Worldwide, the annual generation of e-waste is rising by 2.6 million tonnes annually, on track to reach 82 million tonnes by 2030

Most of this e-waste ends up in developing countries and eventually in landfill sites, creating clear negative consequences:

Any discarded product with a plug or battery, is a health and environmental hazard, containing toxic additives or hazardous substances such as mercury, which can damage the human brain and coordination system.

The report foresees a drop in the documented collection and recycling rate from 22.3% in 2022 to 20% by 2030 due to the widening difference in recycling efforts relative to the staggering growth of e-waste generation worldwide.

One benefit of SoftPOS is that as well as business owners not needing to buy a specific payment machine, existing devices such as iPhones, or higher-end Android devices, benefit from the extensive environmental programmes that tech companies have in place. Apple’s latest annual Environmental Progress Report stretches to 126 pages. It covers everything from the growth of clean energy in their supply chain to how packaging is reducing with each new iPhone release. Similarly, on the Android side, Samsung also has impressive credentials in its sustainability reporting.

SoftPOS is part of a wider trend in payments: the move from hardware to software.

Yet hardware will always have its place. In some environments, specific payment devices will still be needed. Businesses in some sectors prefer sturdier hardware than a standard phone. But the trend away from payment-specific devices is clear. SoftPOS will grow as a share of the POS market, and other payment options, such as QR codes, are now the norm in many parts of the world.

Fintech more widely is synonymous with digitalisation. Neobanks eliminate branches. Digital receipts via email or SMS replace paper receipts. Physical cards are replaced by virtual cards. Even if you don’t particularly care about being more sustainable, fintech is, by default, better for the planet than legacy tech.

That said, digitalisation can have its own risks. Older people and those with other needs may still need cash, and I’m not in favour of a ban on cash. A recent European Central Bank (ECB) report examined the environmental impact of Euro banknotes, covering the full gamut from raw materials and production to transportation and disposal. Cash is still the most popular payment method int he Eurozone overall, so it’s nice to see the extent that the supply chain’s impact is understood.

Options beyond ESG

As noted at the start of this post, ESG has fallen out of favour in some quarters.

Often ESG metrics come from regulators or institutional investors, and can be a box-ticking exercise, or a way of showing that a company is keeping up with its peers. When ESG is mandated, it can feel less genuine. I can’t help but think, ‘does this company really care?’, or is it something they just do for compliance reasons? If it doesn’t feel genuine, then people will pay less attention.

With this in mind, in recent years, voluntary certifications have become increasingly popular. Companies can demonstrate their genuine commitment to sustainability and social causes through accreditation and actions.

1% for the Planet (1%FTP) was started by Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard in 2002. It’s a global network of businesses that give at least 1% of their revenue each year to approved environmental nonprofit organisations. At the end of 2023, companies from more than 60 countries were represented in the B Corp network, and the total amount given by members so far is over $500 million.

According to 1%FTP, 43% of UK consumers say a 1%FTP logo positively influences purchasing decisions, and with Gen Z, that number rises to 51%. This indicates that in some markets, having a voluntary certification can be a powerful brand indicator. It can signify that the brand is considering more than quarter-by-quarter profits, and the 1% in donations, can be more than made up by additional sales generated by the halo effect from participating in the scheme.

My view: 1%FTP is a great idea, but when I looked into it further, I was surprised to see just what a wide range of organisations qualify as accredited nonprofits. Personally, I would prefer more curation of the donation options. One aspect I do like is that 50% of the value of donations can be in the form of volunteering time or other non-monetary support.

Another voluntary certification scheme is B Corp. The certification process involves an extensive assessment of environmental impact, social responsibility, and transparency practices. Companies need to recertify every three years to keep their B Corp status intact. It’s this third-party verification that makes B Corp status so valuable. It takes a lot of hard work to achieve and is far beyond basic box-ticking.

The main way to describe the B Corp mission is going beyond profits for shareholders and ensuring that companies consider wider stakeholder impact, including their workers, customers, and communities. Over time, B Corp standards change - they’re now in their seventh iteration. Companies can’t rest on their laurels once certified; they need to keep up with the evolving standards and show continuous improvement.

My view: B Corp certification only seems to grow in importance over time. The number of B Corps in the UK increased by 40% between 2023 and 2024. Fintech start-ups such as Clowd9 and Felloh are B Corp certified. The rigorous auditing of supply chains and working practices makes it likely that an organisation with B Corp status is a well-run organisation, so it’s great to see British fintech companies going through the process.

Climate action without complexity

B Corp and 1%FTP are rewarding and valuable, but they require considerable time and effort. Stripe Climate is quite the opposite. It offers a frictionless option for Stripe users to support climate action.

Within the Stripe dashboard, users can opt in to Stripe Climate and select what percentage of their sales to allocate to carbon removal programmes.

In a future edition of this newsletter, I’ll take a closer look at Stripe Climate. How does it work, what does it fund, and is it actually making a difference?