How India's Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) is changing payments

India's tech stack is building innovative payment solutions at home and abroad

In the 2020s, infrastructure is key. From high-speed broadband to high-speed trains to renewable energy infrastructure. Every country is developing their infrastructure at pace.

Sometimes, national infrastructure is built solely with in-country expertise. Other times, external entities such as foreign governments or international institutions may offer financial or material support.

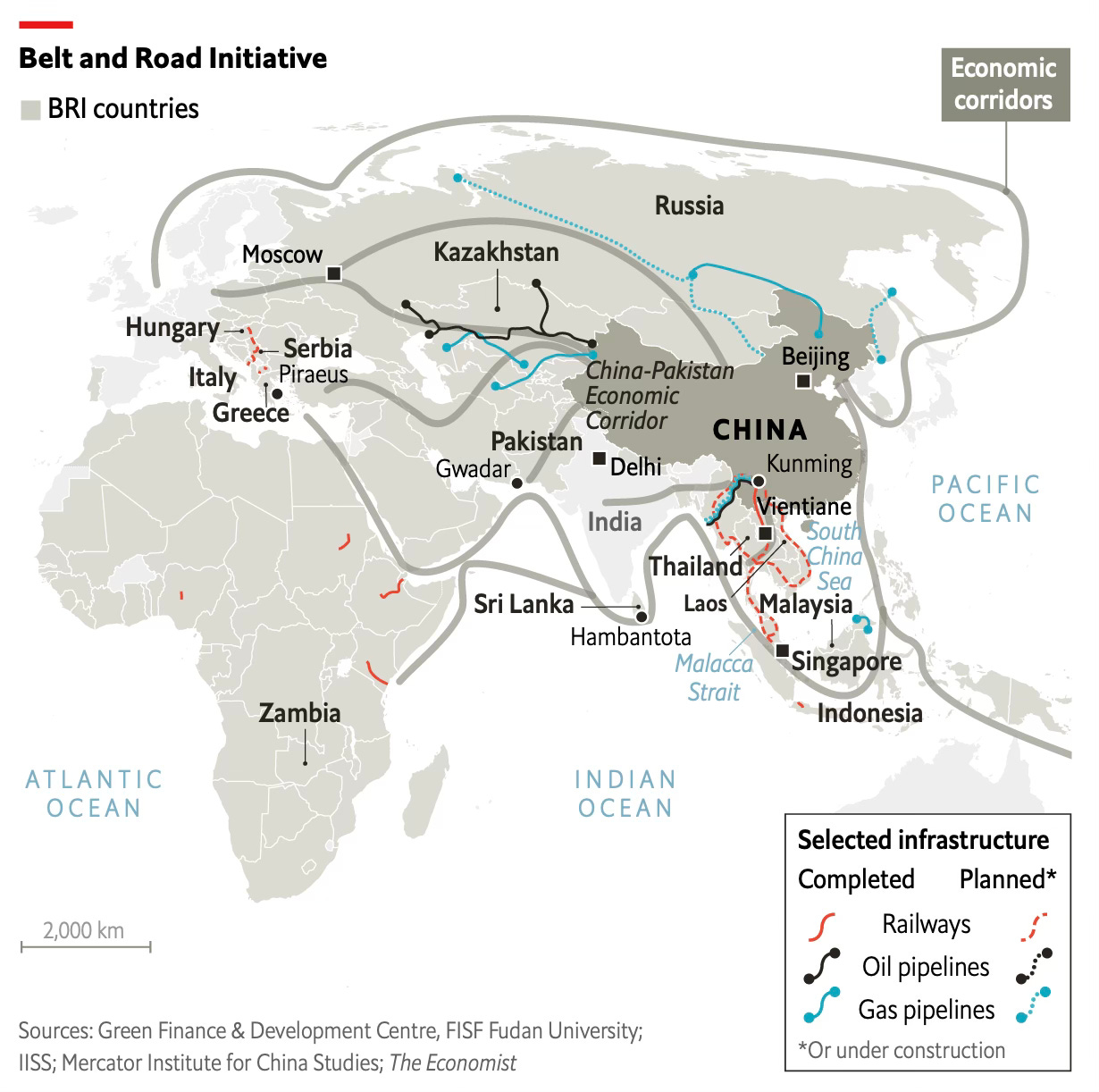

China's Belt and Road initiative is a famous example of infrastructure development with outside help. So far, over 150 countries have signed up to Belt and Road initiatives. Some estimates put the combined value of all Belt and Road projects at over $1 trillion.

With Belt and Road, China has built alliances, particularly in developing economies. And Chinese companies have been able to gain a foothold in new markets. There are criticisms of Belt and Road, yet recipient economies have been able to build bigger and faster than they would have otherwise.

In April 2023, the Vientiane-Kunming railway line opened. Connecting the capital of Laos to one of the most import cities in South-Western China. Laos would not have had the resources to build high-speed rail without Chinese help.

And Indonesia has recently opened a new high-speed rail line with Chinese help. Reducing the journey time from Jakarta to Bandung (the 3rd largest city) from more than 3 hours to less than one hour. Railway diplomacy has been a big success.

We can make a comparison here between India and China. While China's Belt and Road has focused mainly on physical infrastructure, India's initiative is Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI), which is centred on software and digitalisation.