How Japan pays - payments in Japan

Exploring payment habits in the land of the rising sun. Taking a look at how people pay for goods & services, the role of culture, and the impact of technology.

This post is a collaboration with the Hidden Japan substack. Hidden Japan covers many aspects of Japanese culture and society and is always a great read.

Japan is a country that effortlessly mixes the hyper-modern and long-cherished traditions. Both aspects of life exist side-by-side in a way rarely seen in other countries. For example, you can stay in a hotel staffed by robots, and the next day, walk around the Gion (祇園) district of Kyoto. Here you will see modern geishas dressed much like they would have been hundreds of years ago. You may feel that you've travelled back in time as you are surrounded by a Japan of centuries gone by, especially when the bill comes and you're counting the cash.

The Cultural Difference

In terms of digital payments, Japan is somewhat stuck in the past. Cash usage is much higher than in other East Asian economies. In Korea, businesses with revenues over $20,000 are required to offer card payments, and Japan has also fallen behind its larger neighbour, China.

In China, mobile payment apps, such as AliPay are so ubiquitous that paying by cash can be difficult. In Japan, it’s almost the opposite. Many businesses still insist on cash. In big cities, at locations such as train stations and hotels, it’s possible to pay with a credit card. But even some city convenience stores are cash only.

According to data from the Bank of Japan, the Japan Consumer Credit Association and the Payments Japan Association, cashless payments are rising. The COVID-19 pandemic fuelled a rise in demand for contactless payment options, and these habits have since remained. The latest available data is for 2022 and shows a significant growth in cashless payments:

Cashless purchasing reached 111 trillion yen ($838 billion) in 2022… The 17% annual gain lifted the total above 100 trillion yen for the first time. While 36% of consumption in cash-loving Japan was covered by these [cashless] payments last year, the share remains below that of Western markets, where the cashless ratio hovers around 60%.

Such payments in Japan are defined as purchases made through credit cards, debit cards, QR code apps like PayPay and prepaid e-money such as transit cards. Credit cards are the most popular option, rising 16% last year to 93.7 trillion yen.

Whilst in Japan cash accounts for over 60% of total payment volume, in the UK it’s less than 20%. What drives Japan’s propensity for cash usage? Firstly, there are cultural factors. Payments by card are associated with credit and debt in Japan, and there’s less propensity to accumulate debt compared to many Western countries. In Western Europe, Germany can be somewhat similar, where getting a credit card - that is not paid off in full each month - can be a struggle.

For many Japanese people, cash feels more secure, and in a high-trust society, there’s little risk of forged banknotes and little chance of robbery and theft. (According to a report mentioned in The Banker, Japan’s robbery rate per 100,000 people is around 100x less than that of France and the United States.) Electronic payments may inherently feel more risky, especially in a rapidly ageing society - Japan’s population is set to drop by 20% by 2050. Furthermore, Cash is embedded in ceremonies and celebrations. Many Japanese will get fresh bills to present to family members as New Year’s gifts, in envelopes known as pochibukuro. This tradition has deep-seated cultural origins:

The gesture [of gifting pochibukuro] was a matter of etiquette and selecting just the right pochibukuro became an art form in itself. It was fashionable to carry a selection of these envelopes on your person in order to mark the occasion with the appropriate level of taste, wit or humor. The tradition stems from the Edo period [between 1603 and 1868] practice of giving gratuities to kabuki actors, geisha and courtesans, but inn owners or tradesmen who provided services were regularly given these small monetary gifts as well. Decorum dictated that these offerings were to be made discreetly with the sum carefully concealed, so as not to embarrass either party.

As well as societal factors, regulatory reasons also impact the growth in cashless payments in Japan. In the EU and the UK, the costs of card payments are regulated. In these territories, the interchange fee, paid when accepting a card payment, is regulated at 0.20% for most debit cards and 0.30% for most credit cards. In Japan, this fee can be well over 2%. A high acceptance fee means many small businesses prefer to stay with what they know - especially as they are so comfortable dealing with cash.

According to Nikkei’s Natsumi Iwata, the high fees and even a lack of transparency are holding Japan back in its cashless transformation:

Japan is promoting cashless payments, and sees the burden on stores from commissions for card use as a factor hindering their spread. The country's Fair Trade Commission and the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry have asked international card brands to disclose their fees for stores, which Visa, Mastercard and UnionPay did for some fees in 2022 for the first time.

Japan’s Payments Innovation

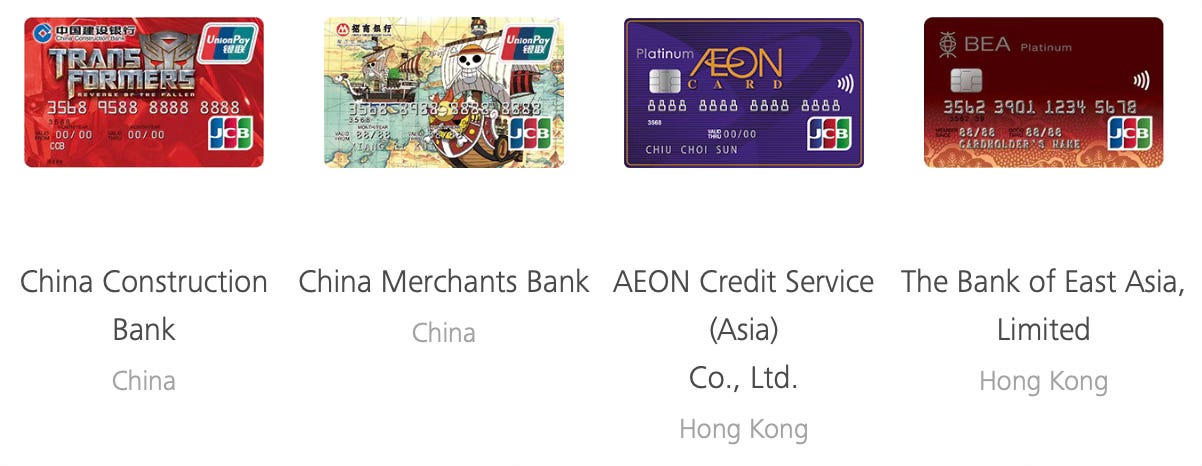

Despite the challenges noted with cashless payments in Japan, some success stories have occurred. JCB (Japan Credit Bureau) started in 1961 as a card network. Japanese banks were able to use the JCB network to issue cards rather than using the large American card brands - Visa and Mastercard. It didn't take long before JCB became a vital pillar of the Japanese financial sector.

With a sizeable middle-class consumer base, JCB developed to be one of the largest card-issuing brands in the world. JCB remains within the top echelon when considering the number of cards issued. It sits alongside large international brands such as Visa, Mastercard, American Express, China Union Pay, and Discover - which also owns and operates the Diners Club brand.

JCB is now used in approximately 190 countries globally. Acceptance has developed via various local partnerships. For instance, many banks in Asia and the Middle East provide their customers with JCB cards, often in a co-brand arrangement. In this arrangement, the JCB brand sits alongside another local card network on the same card. Either card brand may be used depending on the territory where the card is used.

Another distinctly Japanese payment innovation is the Konbini payment. As it sounds, this should be convenient. With this technology, a transaction begins online and triggers a payment code. The code that was generated is then entered into a kiosk in a convenience store, and the kiosk prints a voucher code. The voucher must be handed to the in-store clerk, who is paid in cash for the transaction. While this may sound less kombini, the popularity is clear, they make up around 10% of e-commerce payments in Japan. This is the most common form of payment when ordering for live events including concerts and sporting events. Japan must have taken a look at Ticketmaster and thought, how can I add more people to this process.

That being said, there are actual uses for this technology. According to Patrick McKenzie, a key strength of this payment mechanism is its accessibility and ease of use:

Literally anyone can use them. Salaryman, child, and immigrant alike are equal in the eyes of the konbini system; it turns cash into HTTP requests for them all

Adyen’s website features a clear visual flow of a Konbini payment, which is worth taking a look at, especially as it’s so unique compared to what many of us are used to.

One well-known aspect of Japanese pop culture is vending machines. They can provide everything from hot cans of coffee to hamburgers and even alcohol - some have ID scanners, but most do not. Yet, it’s rare for Japanese vending machines to allow non-cash payments.

In some cases, Suica or Pasmo cards can be used to pay at vending machines. These pre-paid cards are usually for journeys on Japan’s public transport system, but they can also be used in some other places. Suica and Pasmo can be compared to Korea’s T-Money or Hong Kong’s Octopus card systems.

The Rise Of Asia’s Digital Wallets

Throughout Asia various mobile wallets have grown in popularity in recent years. For instance WeChat Pay in China, JKOPAY in Taiwan, and PromptPay in Thailand. Now Japan has its own mobile wallets that are growing in popularity. The big story for Japanese payments has been the collaboration of two of their biggest companies, Softbank and Yahoo Japan (who are doing much better than any other Yahoo).

With no similarities in name to any other payment system, PayPay has become Japan's most popular digital payment system in a few short years. Launched in 2018, PayPay is mobile payments but done differently. The payment is conducted via QR codes for each transaction. Each time you need to pay for something, you open up the app and scan the merchants register code. This is an instant payment where you can then show the merchant that funds have been successfully transferred to their account.

It's hard to pinpoint why PayPay has become the popular digital choice over the prevalent tap and go, mobile banking or simply credit cards. Maybe it reaches into the Japanese love of photos. Maybe it feels more secure.

Whatever the case, PayPay has widespread adoption, and has enticed new entrants to this underserved market of Japanese fintech. Companies like the social media giant Line and online e-commerce Rakuten have lined (and Rakutened) up with similar apps. This has led to anticompetitive choices with the apps not accepting different cards. So now instead of choosing your bank on their rates, it's become almost necessary to choose based on which merchant accepts which app.

While Japan may seem extremely cautious in their payments, the rapid ascension of PayPay and their competitors suggests that consumers are ready for a cashless world. Payments and Japan will have to keep up!

If you enjoyed this post, please consider liking or leaving a comment. It's much appreciated. And please consider subscribing to receive future posts via email or in the Substack app.

Thanks for the interesting story. One thing I like about Japan is diversity. For instance, now everybody owns a mobile, but thankfully you can still find many telephones boxes around town (probably because in case of a big earthquake, mobiles become useless).

Same thing with payment. Call me old-fashioned (or worse, if you prefer) but I still prefer cash. I just hate it when they try to force people to adopt a new technology. I want to be free to choose.