Neobanks (Part 2) - success or failure?

Analysing the UK's neobanks

This is the second part of a two-part series on neobanks. Part One, published last week, looked at what defines a neobank and how they differ from legacy banking institutions. This second part examines the varying and evolving strategies of the UK’s big three neobanks - Monzo, Revolut and Starling Bank.

Neobank strategies

Fintechs succeed, at least at the start, by building a wedge. They focus on a specific use case and make sure they can do one thing much better than any incumbent. Neobanks also took this approach, focusing on offering 0% Foreign Exchange (FX) fees when spending abroad. There were 86 million overseas trips by UK residents in 2023. British people like to travel, and this product offering was popular.

From building the initial wedge of 0% FX margin, the UK’s three biggest neobanks all went on to develop their own unique growth strategies. These differences were part tech and part culture. Each founder had their vision of how banking could be better. Neobanks saw the traditional approach to banking as something to be built upon and disrupted, not just replicated.

Of the three main UK neobanks, Starling Bank has achieved several notable firsts.

They got their UK banking licence first, back in July 2016. They launched business bank accounts first. They were the first neobank to become profitable and have remained so for the past three years.

Starling has been the neobank with the most traditional approach to growth. They’ve garnered a reputation for doing the core elements of banking well, winning multiple awards in the process. Rather than expanding into Europe, they are now looking to grow their banking software business. Engine by Starling is a cloud-native banking platform, seeking to take the best of Starling’s tech and sell it to other banks to upgrade their legacy infrastructure.

I saw Nick Drewett, the Chief Commercial Officer of Engine by Starling, give a talk at a recent fintech event in London. As part of Nick’s talk, he discussed Starling’s engineering-first culture. It was interesting to hear how staff can build products, test them internally, and then deploy in a live environment with a group of employees. Then, after reviewing feedback, decide whether to launch to the public at large. This engineering-first culture highlights how Starling is able to maintain the high velocity of new features with no drop in quality. Product improvements, which may take legacy banks months, can be done in days or weeks.

Taking their tech to other banks via Engine is what Starling hopes can drive up their valuation. Some investors estimate that Engine can give Starling a £10bn valuation within the next few years. Engine has only two clients so far, AMP Bank for Australia and New Zealand, and Salt Bank from Romania. The goal is to get to 40-50 clients and generate hundreds of millions of pounds of revenue from Engine. (Starling’s own UK business generated revenue of £682.2m in the previous financial year.)

But selling to banks is hard. Rupak Ghose has noted that in this field, Starling is competing with several specialist cloud-based core banking providers such as Mambu, Thought Machine, and 10x. None of these companies have found the going easy recently:

The bottom line is that legacy banking software either from legacy vendors or in-house builds is sticky and difficult to displace. If the sexy core banking start-ups like Mambu, Thought Machine and 10x are finding the going tough for Starling Engine to become a multi-billion dollar business may be pie in the sky.

It’ll be fascinating to see how Engine by Starling does in the next few years. Its success will not impact Starling Bank in the UK, but if Engine does not perform as hoped, then I wouldn’t be surprised if Starling pivots and looks to expand internationally itself. At one point, expansion to Ireland has been considered.

Moving onto the second of the big three UK neobanks. Monzo has matured in the past few years. The original goal was to build a bank for a billion people around the world. Tom Blomfield, the founder of Monzo, now admits that this ambition will likely never be met, but successfully building a bank for 10 million people in the UK is no mean feat.

In terms of strategy, Monzo’s initial plan was to be a financial hub, somewhat like we now think of super-apps, as annunciated back in 2017:

Our goal is to build a financial control centre, a single hub that you can use to manage your entire financial life. In order to give you access to the best products and services from across the market, we believe that hub should be a marketplace.

By this time, Monzo had its banking license but didn’t want to provide all products and services directly. Instead, they wanted to connect users with various third-parties and be the central point for users to view and interact with multiple financial products. For savings accounts Monzo connected to specialist providers such as Oaknorth and Paragon Bank. This meant they had to do less work in building out their product set but had to share revenue with the third parties involved. Also, as the deposits were not on Monzo’s balance sheet, they could not make corresponding loans to customers from these deposits (more on this later).

Regarding strategy, Monzo is not looking to expand into Europe, but US expansion is underway. Yet this has stalled time and again. In 2021, Monzo failed to get its US banking license. The FT reported that US regulators were cautious about allowing “lossmaking start-ups to become banks”. This was different to the UK, where regulators had been less strict in handing out banking licences.

After withdrawing its US banking application, Monzo decided to become more of a bank themselves. They started to bring their savings offerings in-house and focused on growing their personal loan book. Whilst the financial hub model may have had some good ideas, at its core, it didn’t make the financial returns required. The company was loss-making, and turning it around meant getting better at core banking whilst keeping its fintech edge.

In 2021, amid the BNPL (Buy Now Pay Later) boom sweeping the world, Monzo started to offer a product called Flex. In addition to being able to pay for products in three equal instalments with no charge, users could opt to increase the number of instalments for an extra cost. This flexibility and ease of use was something that legacy banks couldn’t match. A user can choose to “flex” any transaction over a specific value from within the Monzo app. Flex offers BNPL at the card issuer rather than at the merchant level, with the latter being more common.

Lastly, Monzo’s approach to marketing and branding has been notable. Banks are usually conservative in this area, but Monzo changed this. A large part of Monzo’s success has been its viral marketing. Its hot coral coloured cards are well-known, and the bank’s tone of voice is more like talking to a friend than how a bank would traditionally speak to a customer. Millennials and Gen Z may have been the initial target audience, but these days, those of all ages have accounts with Monzo.

Revolut is one of the best-known neobanks in the world. Whilst it was started in the UK and still has its head office in the UK, Revolut now operates as a licensed bank in over 30 countries.

In addition to the geographic expansion, Revolut has gone above and beyond what would be considered the standard offering in a bank up until now. They’ve built stock trading, crypto trading, commodities trading, business accounts, and accounts for those under 18 - to name but a few of their offerings. As a personal account user, you can opt for a free account or pay up to £540 per annum for an Ultra account, which features a plethora of additional features.

Revolut has something of a cult following. There are accounts on X focused just on tracking the latest Revolut news. Their route to a UK banking license has been followed incessantly over the past years. And of the three big UK neobanks, Revolut seems to get the most media coverage. But what will users make of reports that Revolut is looking to sell customer data to advertising partners?

More deposits needed

So far, my writing on this topic may seem like nothing but good news for neobanks. Their valuations are good, and in the case of Revolut, it’s excellent. All three are now turning a profit, and all three have many millions of users in the UK and beyond. So what’s the downside? Because there is a downside.

A recent long-read in the Financial Times by Akila Quinio titled Why fintech upstarts have failed to unseat UK banks mentions:

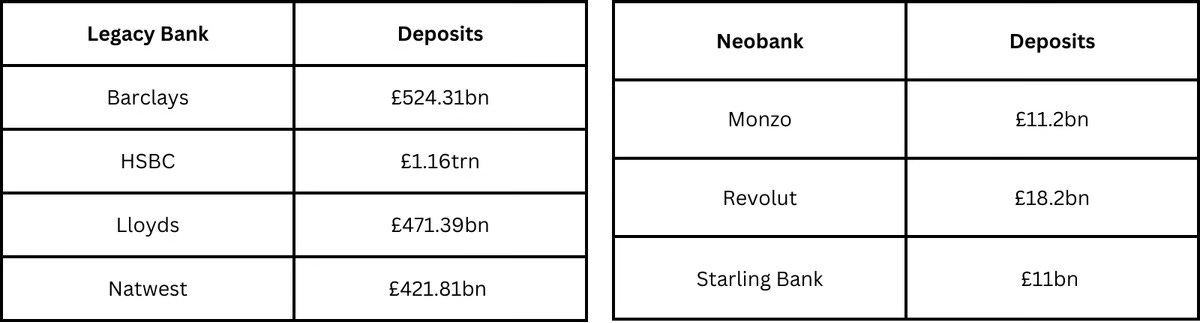

Critics say consumers are using neobanks as a convenient payment management service, rather than as a replacement for traditional current accounts.

There is a valid point here. To take an example, Monzo may have at least 9.3 million customers, but only a small percentage of these customers use their Monzo account as their primary bank account. (The data showing the ratio of Monzo account holders using the bank as their primary account hasn’t been published for a while. Based on historical data, I would estimate that 30-40% of the bank’s customers use Monzo as their main bank account.) It’s common for Brits to maintain their main bank account at a legacy bank and use Monzo - or another neobank - to split bills with friends and spend money when travelling abroad.

There’s an implicit recognition that neobanks make life easier for customers, yet many users are concerned about moving their primary banking, and having their salary paid into a neobank account. This is partly inertia. Only a small percentage of consumers change their bank account each year - it can seem like a scary process. Many users keep a float in their neobank account for ease of transferring money to friends and tracking spending, but they don’t quite have the confidence to fully move their banking.

The second issue the Financial Times long-read on neobanks pointed out is that of deposits, as highlighted below:

Investors in fintechs are increasingly scrutinising the neobanks’ differing business models and assets, looking for proof they can be durabley profitable and attract sufficient deposits to fund lending… Conventional banks have traditionally offered current accounts at little or not profit to attract customers and provide deposits than can then be recycled into mortgages and personal loans.

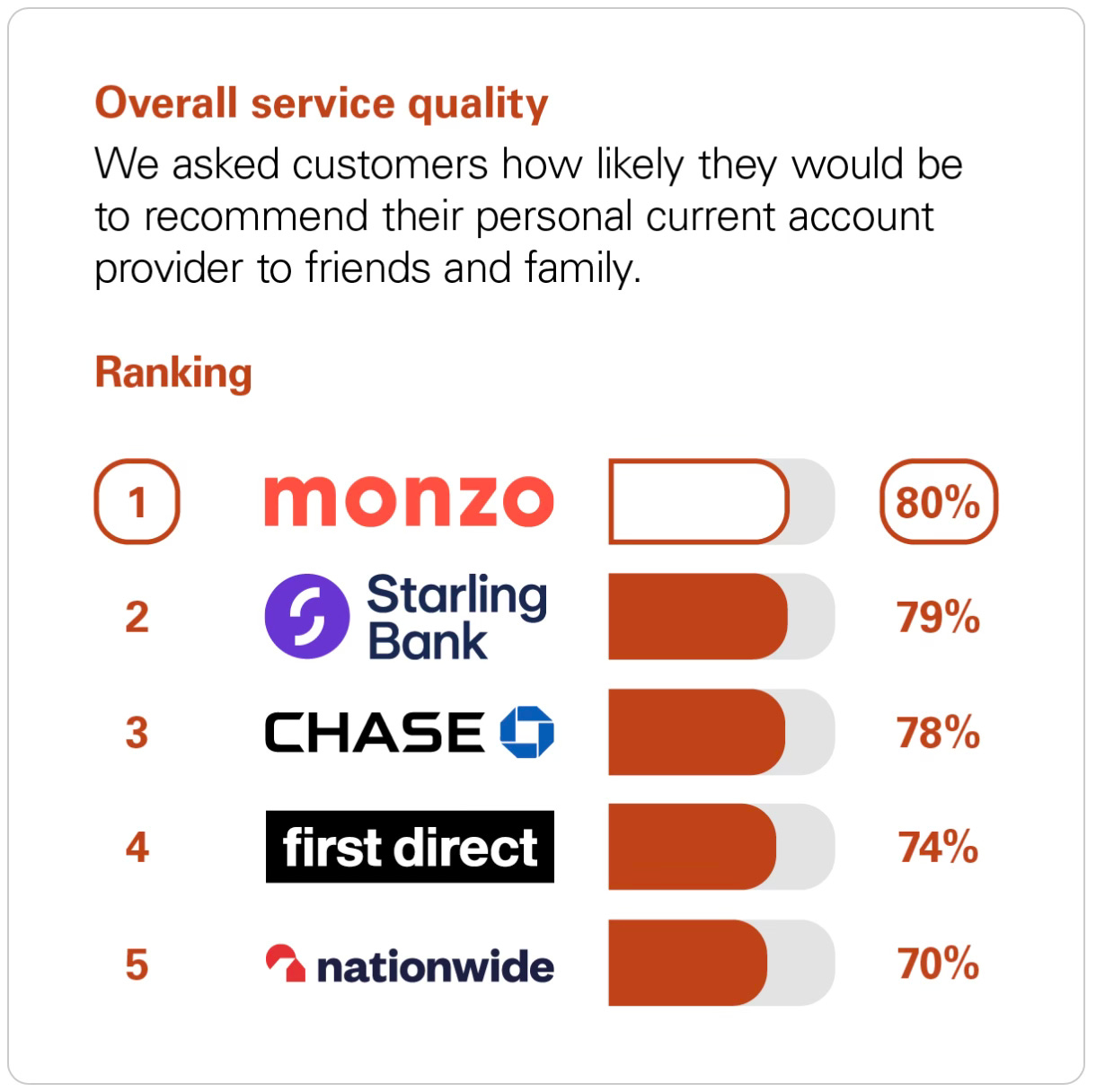

I added the bold text to emphasise a critical point. Neobanks have struggled to capture deposits. Most bank deposits in the UK still sit outside the three big neobanks, with the big four legacy banks capturing the lion’s share.

In recent times, discussions have taken place on the topic of whether deposits are necessary for lending or not. This topic is explored in these Bank of England papers:

Yet, without exploring this discourse in depth at this time, from an analyst perspective, attracting a strong deposit base establishes a credible basis for a bank to operate. A bank’s success in attracting deposits can be compared to that of competitors - whether they be legacy or neobanks.

Banking is seen as a traditional business, and legacy banks have hundreds of years of history, which makes them feel intrinsically safer to money managers and the wealthy. Regardless of the global financial crises of 2007-2008, banks’ heritage means a lot, especially when deposit insurance is just £85k per person. Big money sees institutions that are barely ten years old as a risk. This notwithstanding, neobanks will gradually build up their deposit base over time, but it will not be quick.

Times will change

To round off this post, I’ll share some view on neobanks today and what we can expect in the years ahead. This stems from my view that neobanks have been a success story so far, and we’re only just beginning.

Firstly, neobanks have been successful in building their own business models with their own nuances. Neobank business models are based on being banks at their core and doing banking better. At the same time neobanks excel at offering a diversified set of products and features. As discussed in Part 1, for a long time, banking didn’t change much at all, but neobanks have changed the rules of the game.

Secondly, some analysts and commentators have claimed that legacy banks have stepped up their user experience. Marginally, yes, but if you’ve used Monzo or Starling every day for years, then going back to the bloated UI of a legacy bank can be tough. I’ve used my neobank account as my primary bank for the past six years, and at no point have I wanted to go back to using my previous legacy bank. I believe we will go through a generational change in banking. As time goes by, Millennials and Generation Z, who are used to neobanks, will move more deposits to challenger banks (another name for neobanks). If the tech of legacy banks continues to fall behind, then neobanks will keep increasing their market share and, in turn, their deposit base.

Third, the UK’s three big neobanks have shown themselves to be successful and well-managed businesses. Starling got to profitability over three years ago. Monzo pivoted to BNPL and bringing savings and loans in-house. Revolut has deployed a considerable number of products and features whilst obtaining banking licences in the UK and EU. Neobanks have proven their staying power. Five years ago, there were still many questions about neobanks, but now it’s clear that they are here to stay.

If you enjoyed reading this post, you can connect with me on LinkedIn, X, and BlueSky.

This was very insightful to me :)

Can eurepeans open an account on these banks?