BNPL in the midst of a trade war

Despite the headwinds BNPL is here to stay

Disclaimer: views expressed here are my own and do not represent any other organisation

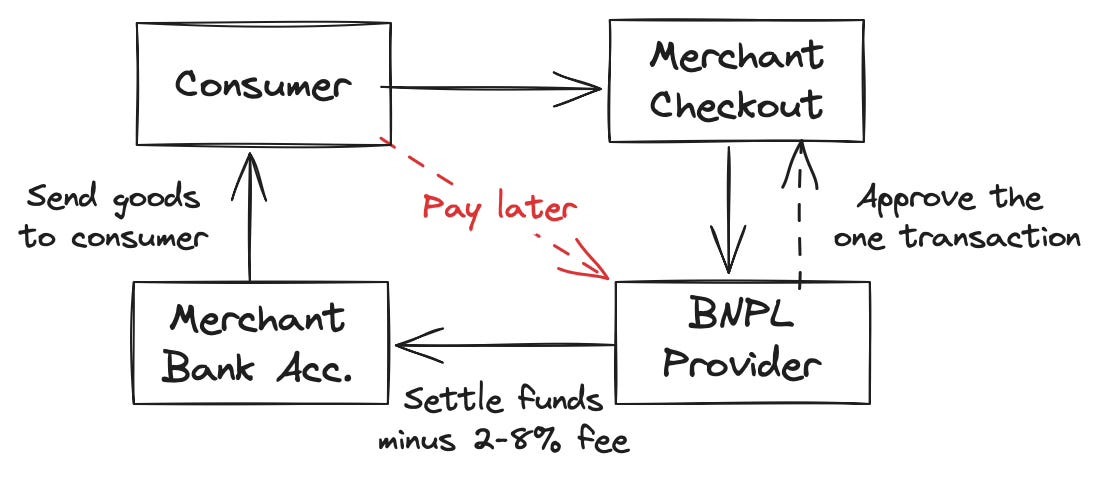

Merchants benefit from offering BNPL payment options in several ways. First, credit and fraud risks are transferred from the merchant to the platform. Second, offering BNPL options allows merchants to reach customers who lack immediate financial means. In some cases, merchants also benefit from non-payment services such as marketing and the data analytics provided by BNPL platforms. This results in a higher share of website visitors who finalise a purchase and an increase in both the number and value of sales.

BIS Quarterly Review, December 2023 (Lux and Epps (2022))

Klarna’s IPO suspended

Six weeks ago, on March 14th, Klarna filed its F1 document with the SEC. An F1 document includes a company’s IPO prospectus and is generally used to generate excitement and whet the appetite of potential investors.

An F1 is the same as the more commonly used S1, but an F1 is for private companies that currently domicile their headquarters overseas. In this case, Klarna has its corporate domicile in London.

Some highlights of the F1 included:

Klarna had 93 million active users across 26 countries in 2024. (Active users are defined in the F1 as those who “made a purchase or a payment using a Klarna-branded product or logged into the Klarna app within the past 12 months”)

In 2024, revenue rose to $2.81bn, up from $2.28 bn in 2023 - a 24% increase.

Most importantly, in 2024, Klara was profitable. In 2023, the company made a net loss of $244m, whereas in 2024, Klarna saw a net profit of $21m.

Everything was looking good, and the company expected to IPO at a $15bn valuation. But on Friday, April 4th, amid a rapidly falling stock market following President Trump’s announcement of widespread tariffs, Klarna suspended its IPO.

A number of upcoming US initial public offerings, including $15bn fintech Klarna… have been postponed as Donald Trump’s aggressive tariffs roil global financial markets. [When a] company publicly files their IPO paperwork with the Securities and Exchange Commission, they put themselves on a footing to launch an investor roadshow after 15 days. Klarna was planning to start the investor roadshow for its $15bn listing next week

The listing has now been delayed indefinitely.

Steve McLaughlin, founder of fintech-focused investment bank FT Partners, told the Wall Street Journal that amidst the market turmoil, there’s no room for IPOs right now. When exactly the market will be ready again is anyone’s guess.

The road to IPO

Klarna’s now-cancelled IPO had been a long time coming. Bloomberg reported that an IPO was in the works way back in December 2019. At that time, CEO Sebastian Siemiatkowski spoke of a float within the next two years yet emphasised that the company wasn’t in a rush to go public. Then came 2020 and COVID-19. The maelstrom that hit the financial markets in early 2020 delayed some IPOs, as the fast-changing market sentiment led to some companies assessing their options.

As the pandemic put global travel on hold, Airbnb was one high-profile IPO delay. The company finally went public in December 2020 in the biggest public offering of the year.

In 2021, both private and public markets were exuberant. Driven by the e-commerce boom from working at home and lockdowns, companies such as Shopify and Alibaba hit all-time highs. Amazon hit a market cap of $1.72 trillion on July 8th 2021 and didn’t return to this level again until mid-2024.

In the private markets, companies such as Stripe achieved a valuation of $95bn in 2021, making Stripe the biggest private fintech company in the world at that time. Stripe’s most recent fundraising, a tender offering to employees and investors in February 2025, saw a valuation of $91.5bn, which is below the 2021 valuation despite payment volume more than doubling during the past four years. In 2024, payment volume hit $1.4trn.

Similarly, Plaid achieved a private valuation of $13.4bn in 2021, yet Plaid’s latest fundraising round saw the company valued at $6.1bn. Plaid CEO Zach Perret told the Financial Times that “tech multiples have massively compressed between the time that we raised last and today”, which is clearly the case, as despite rising sales, fintech valuations have not grown accordingly.

When it comes to Klarna’s valuation, the past years have been a rollercoaster in private markets:

In 2019, when Sebastian Siemiatkowski spoke to Bloomberg about an IPO on the horizon, the company was valued at $5.5bn.

In September 2020, Klarna achieved a valuation of $10.65bn following a 650m funding round.

In March 2021, amid the post-COVID e-commerce boom, Klarna’s valuation surged to $31bn.

In July 2021, in a funding round led by SoftBank’s Vision Fund 2, Klarna’s valuation rose further to $45.6bn.

Yet in July 2022, Klarna was valued at $6.7bn, an 85% decrease from the previous year’s valuation.

This sharp reduction in Klarna’s valuation in 2022 wasn’t unique. It was a year of changing factors in the global economy. Rising interest rates and inflation impacted both private and public markets alike. Tech companies struggled, with Meta, Netflix, and Amazon all dropping more than 50%.

In 2022, Klarna made a loss of more than $1bn, its biggest loss to date — an increase of 47% from 2021. The next few years were about improving efficiency and cutting losses. The company showed its resilience by weathering a substantial downround and achieving profitability in 2024. However, we will have to wait still longer for the next step, the much-anticipated IPO.

BNPL is short-term lending

Klarna may seem different from traditional lenders, such as credit card companies and loan providers, but Klarna is still a lending business. The key difference between credit cards and BNPL is that BNPL offers short-term lending, with credit provisioned for a specific purchase.

As a comparison, credit cards operate on a longer-term basis, in an arrangement that continues until one party decides to withdraw from the credit agreement. The credit amount may be changed during the agreement by increasing or decreasing the overall limit. Usually, a limit increase should only be with a user’s consent (although not always). However, a limit decrease may happen unilaterally if the lender wishes to reduce their perceived risk.

The business model of card issuing is to offer credit on a total value basis. A lender provides a credit line for users to utilise as they wish (within reason). The user can pay the minimum balance each month or opt to pay in full. If an unpaid balance rolls over to the next month, the user will pay interest, which is added to the total balance.

With BNPL, any balance is paid off in full within an agreed short-time period or in monthly instalments, with three or four monthly payments being the most likely option. In theory, BNPL is supposed to avoid some of the less salubrious elements of the credit card business model, such as late payment fees. However, Jason Mikula found that 13.6% of Klarna’s revenue now consists of such fees:

There are some signs Klarna users are struggling to keep up with their payments: the company earned some $254 million in “reminder” (late) fees on its pay-in-four and pay-in-30 products, and another $128 million in “snooze” fees on its interest-bearing loans.

Interestingly, Klarna’s main competitor in the US, Affirm, seeks to differentiate itself by emphasising that it doesn’t charge late fees, or what it refers to as junk charges:

Affirm has been upfront in our approach to never charging any late fees, hidden fees, or other junk charges. Since our founding, we have said that we refuse to make money off of people’s mistakes or misfortunes. Our business aligns our interests with those of consumers and merchants. Consumers can make better, and more informed, purchasing decisions when they are able to understand the full cost of credit upfront for each transaction.

Of course, despite the lack of late fees, late payments still have consequences. Affirm may restrict the use of its service, and late payments can hurt a user’s credit score. While Klarna’s average loan length is 40 days, Affirm’s is significantly longer, at 11 months. The differential makes the likelihood of missed payments higher with Affirm’s customers.

Many economic commentators see a rising risk of recession. A Reuters survey of senior economists put the chance of a recession in 2025 at 45%, up from 25% a month earlier. If there is an economic downturn, BNPL companies will be impacted differently. Affirm has a higher take rate than Klarna but also a higher payment default rate. Partly, these differences are due to differences in loan duration. With a longer loan comes more margin but at a higher risk.

If a recession occurs, this means a rise in unemployment as companies cut headcount to weather the storm. If unemployment rises, consumers are more likely to default on future payments. In a recession, BNPL usage could rise as consumers opt for more BNPL instalments instead of debit cards as a way of spreading out payments. In such a scenario, controlling for bad debt and tightening the credit approval processes will be key. However, BNPL has succeeded by making the provision of credit seamless, and this challenge of controlling for ease of use and bad debt provision has yet to be tested in a recession.

Klarna emerged pre-Apple Pay, pre-Shopify Pay, pre-Stripe Link. It was one of the first fast checkout solutions, with no need to enter a card number or a password. Only a small amount of information was required to proceed with a purchase. In the UK, for a repeat customer, sometimes just an email address and postcode would be enough. This ease of use was a selling point for BNPL, but this part of the solution has been somewhat forgotten in recent times. Now many other fast checkout solutions. Still, the ability to complete a payment with minimal information helped position BNPL as something quite different to cards. The credit provision at the Point of Sale (POS) and ease of checkout combined to allow consumers to experience a new era of online shopping.

In the first days of the Trump tariffs, not just Affirm but other, more traditional lenders plunged, due to uncertainty and recession fears. But Affirm saw the largest drop among not just lenders but a wider group of fintech companies, with its share price declining 19% on the Thursday following the tariff announcement. Some weeks later, the share price has recovered, yet concerns remain about a recession, so continued volatility can be expected.

On the origins of BNPL

Klarna started in Sweden in 2005 with a simple original product: don’t pay upfront, receive the goods immediately and pay within 14 days.

Klarna’s offering built on a tried and tested formula from business-to-business (B2B) payments.

It’s common for businesses to pay suppliers in 30, 60, or even 90 days after receipt of goods or services. One way to look at BNPL is that Klarna brought the concept of payment on invoice, a B2B business model, directly to consumers.

Soon, the sweet spot was e-commerce, especially clothing and apparel.

Users could “buy” three items and send one back before payment was due. The new updated invoice would reflect two, not three items, so payment would be made only for the two that the consumer kept. There was no charge for sending back the unwanted item. Postage was often free, and if the reason was the wrong size, colour didn’t suit, or anything else, returns were accepted with no qualms.

Following the same process with a credit card would mean a user is debited for the full amount. Later, they would have to check if they received a refund for the item they sent back. Klarna offered a smart user experience - consumers didn’t need to check if they successfully received a refund.

Klarna’s second market was Germany. Both Germany and Sweden had a low credit default rate - it was rare for consumers to miss payments. Both markets traditionally had a lower take-up of credit cards than the more credit-card-centric UK or US. Klarna wasn’t seen as credit; it was seen as something different.

When Klarna entered the UK market, an early success story was the Arcadia Group, the parent company of the now-defunct Topshop. By 2018, a slightly different model soon predominated - that of instalment payments. Buy Now Pay Later evolved into something wider than the original solution, but the moniker remained. Instead of paying in one single payment after receipt of the goods, a user could now split the value of a purchase into three equal monthly payments. The first payment would be taken up front, and subsequent payments would follow in the next months.

Instalments were nothing new in payments. E-commerce transactions in places such as Greece and Brazil had long offered instalments, usually interest-free. But instalments were new to Western Europe. With Klarna, merchants would pay a higher fee for BNPL compared to card payments on the proviso that, with Klarna, users spent more. To use the payment industry’s vernacular, BNPL “increased basket size”.

Nowadays, when most people think of BNPL, instalments come to mind. The success of the business model can be seen throughout the world. Many markets and regions now have their own BNPL success stories. In Southeast Asia, Atome is a leading provider, and in the Middle East, Tabby has seen success in Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Kuwait. Each company brings its own nuances in terms of how they assess lending, provision credit, and develop relationships with local retailers.

Along with BNPL-specific providers, many banks and card issuers now offer instalment payments within a traditional credit framework. A total value is approved upon application for credit, and the instalment payment sits within this existing credit line. Lenders allow users to turn a card transaction into an instalment plan after the transaction has taken place. An example of this is Monzo’s Flex product. Flex allows users to take any transaction over £100 and spread it over 3 months, with three equal monthly payments at no cost, or extend to 6 months for an additional fee. All costs and options are shown transparently in-app.

BNPL is here to stay

It’s easier to be approved for a BNPL purchase than for a credit card. But remember, with BNPL, the approval is for one purchase only, not an ongoing credit line. The ease of use is a double-edged sword, as it has led to worries that users could be approved for multiple BNPL-based payments quickly, which they otherwise couldn’t afford. This has become known as stacking. Users can stack up substantial debt from the accumulation of various smaller purchases. Many smaller purchases feel like less of a burden than one big credit card bill - yet the ultimate impact is the same.

Ironically, in a market of widening BNPL competition, the accumulation of BNPL debt is more likely, not less. The methodologies used to assess creditworthiness differ between BNPL providers. If a user is refused credit with Klarna, they may still be approved by Affirm or Afterpay. On the other hand, with credit cards, credit is provisioned on a tried and tested formula based on credit scores and other known factors. Therefore, for some users, BNPL may be inherently riskier than getting a credit card-based credit line (if they can get approved for one). Nonetheless, BNPL is here to stay, and its popularity is rising, growing at a 27.5% CAGR in the US in the past three years (including an estimate of 2025’s volumes).

Another sign that BNPL is here to stay can be seen in the wide variety of sectors and use cases in which it is now offered. Klarna originally saw success with e-commerce, particularly with fashion and apparel, but BNPL has now conquered all parts of the economy. One case in point. Recently, Klarna announced a partnership with DoorDash, the leading food delivery company in the US. With this partnership, consumers can pay for food delivery in instalments. The partnership has stirred some controversy. On one hand, it’s just another form of credit, and we readily accept paying with a credit card for takeout, but the proportion of BNPL late fees are rising. The real cost of a pizza will rise if users don’t make their payments in time. Lendingtree found that:

An increasing percentage of BNPL users pay late. 41% of BNPL users say they paid late in the past year, up from 34% a year ago. Surprisingly, high-income borrowers are among the most likely to pay late, along with men, young people and parents of young kids. However, 76% of late payers were late by no more than a week or so.

Two-thirds of BNPL users say they’d consider using it for food delivery, and many are putting their money where their mouth is. DoorDash and BNPL giant Klarna recently announced a partnership to allow customers to pay for DoorDash deliveries with BNPL. However, we found that 16% of BNPL users say they’ve already used BNPL for restaurant food delivery or takeout.

More than 6 in 10 BNPL users (62%) incorrectly believe making on-time payments on BNPL loans helps your credit score.Only 13% say they don’t help your credit score, which is correct, while 26% aren’t sure. Men and high-income earners are among the most likely to believe this falsehood. Younger Americans are more likely to believe it than their older counterparts, but even 54% of boomers do.

At the same time that late fees are rising, Klarna has made it easier to track outstanding payments in app. Anyone who uses Klarna’s app these days will see a smooth user experience that consolidates all outstanding payments into a single view. If a user has made many purchases with Klarna, the way purchases are displayed in the app looks almost like a traditional credit card app.

This made me think of the phrase “plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose” (the more things change, the more they stay the same). Some users prefer to get their credit via BNPL, yet at the end of the day, it’s still credit, and all credit needs to be paid back. However, younger generations are opting for a different credit experience, which is no surprise given that many credit card apps are not as user-friendly as Klarna and other modern BNPL offerings.

In addition to BNPL, there are other business models that differ from traditional credit and allow users to pay over time. In the above video, YouTuber Cara Nicole highlights that before there was BNPL, there was layaway. Layaway allowed consumers to break up payments into instalments, but unlike BNPL, the product is only received once all of the payments are made, not before.

In places like South Africa, companies like LayUp are offering the layaway business model—known locally as LayBy—for both in-store and online purchases. This model has an element of financial inclusion. Users who couldn’t otherwise afford to buy a high-value item and wouldn’t be approved for traditional credit can still get one. In the US, Accrue offers a stored value wallet that helps businesses build customer loyalty, allowing new ways for customers to save regularly towards a purchase.

Other recent posts on Payments Culture

I recently wrote a post looking back at two years of writing on Substack:

Check out my recent post on stablecoins, featuring Easy, one to watch in this space:

Also, Germany is still very cash-dependent, but how will this work in a world of AI?