Can Revolut compete with American Express?

Looking at the interchange business model in Europe, how credit card rewards are funded, and why American Express is different

Revolut is looking to compete with American Express (Amex) by offering a rewards-based credit card product in the UK. The startup-focused news outlet Sifted reported:

Revolut is in the early stages of developing a points-based credit card, putting it in direct competition with incumbents such as American Express.

It’s the latest in a slew of new products developed by the UK fintech, which has over 50m customers globally and now offers everything from stocks and shares and crypto, to pet insurance.

Sometimes when I read news like this, my instinct as someone with experience in payments is to think: can Revolut really compete with Amex? Or is this part of a broader strategy? Amex has a strong position in the card rewards space, but I'm curious to understand the dynamics more and get into the next level of detail that news stories don't have space for. In this post, we'll go through:

Understanding interchange - the economics behind credit card rewards and why it varies by region

Amex’s regulatory advantage - how the Interchange Fee Regulation (IFR) gives Amex a unique position in the UK and EU

The card rewards calculation - how fintechs structure their reward programmes within regulatory constraints

How credit card strategy is evolving - from standalone premium products to integrated wider financial ecosystems

Understanding interchange

The main factor affecting credit card rewards is interchange. Credit card rewards are fuelled by interchange. It’s part of the fee that all businesses get charged when they allow users to pay with Visa or Mastercard credit or debit cards.

Different countries have different interchange rates for credit card transactions.

The higher the interchange fee, the better the rewards a cardholder gets, especially on credit card transactions. The US has one of the highest interchange fees in the world for credit cards, averaging 2.2% for consumer domestic credit transactions. In the US, consumers enjoy generous reward programmes. However, not everyone benefits, as the best rewards cards are unavailable to those with low credit scores.

The downside for businesses is that high interchange also means that companies pay more to accept card payments.

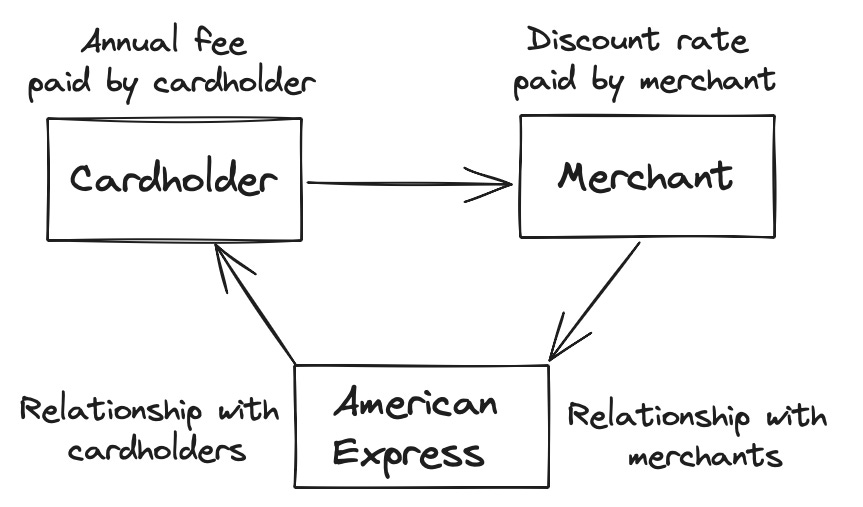

Interchange is actually one of three fees levied by the card acquirer - the entity that charges a business for processing a transaction. Examples of card acquirers in the UK, sometimes known as acquiring banks or simply “acquirers,” are Worldpay, Elavon, Adyen, and so on.

As part of the financial flow of a transaction, the interchange fee goes from the acquirer to the card network, e.g. Visa or Mastercard, and is then paid to the card issuer by the network. The card issuer is the one that provides a credit card to a consumer. Barclaycard, HSBC, and Santander are examples of card issuers in the UK.

In addition to the interchange fee, the acquirer also charges scheme fees (which are paid to Visa and Mastercard), and takes its own cut. Usually, the acquirer charges all three fees as a combined amount, but large retailers expect to see a breakdown of all three elements in a fully transparent pricing model.

The total fee retailers pay is sometimes called MSC, or Merchant Service Charge. The MSC is the sum of interchange plus scheme fees plus acquirer margin.

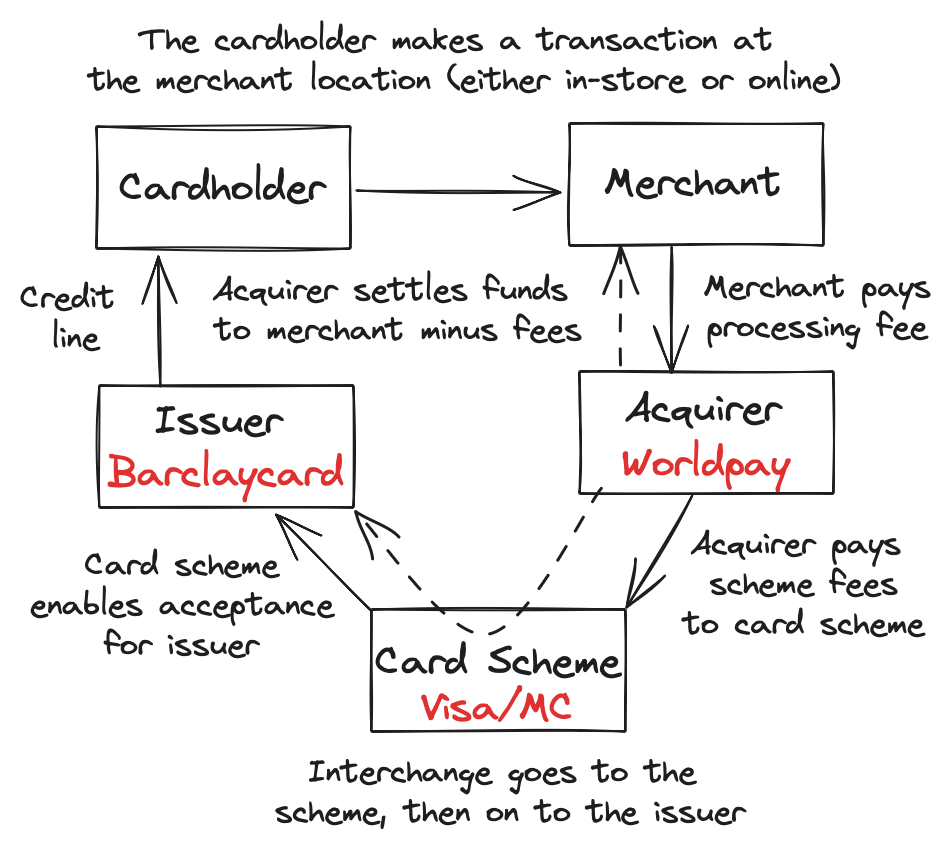

Revolut’s yet to be launched UK credit card will either be Visa or Mastercard branded (they currently offer debit cards badged with both Visa and Mastercard). When comparing any Visa or Mastercard credit card product with Amex, Amex holds an advantage that cannot be matched.

This is due to how credit card interchange is regulated in the UK and EU.

Amex’s advantage

The interchange rates for Visa and Mastercard consumer transactions are capped at 0.20% for debit cards and 0.30% for credit cards. This cap comes from the Interchange Fee Regulation (IFR).

The Interchange Fee Regulation (EU) 2015/751 was passed by the European Union in April 2015 and came into force on 9 December 2015. Since leaving the EU, the regulation has continued in force in the UK, as it was retained post-Brexit. A cap on interchange fees of 0.2% for debit cards and 0.3% for credit cards still applies to most consumer card transactions.

The hope was that the Interchange Fee Regulation (IFR) would lead to lower consumer prices as expressed in the regulation itself:

Regulating such fees would improve the functioning of the internal market and contribute to reducing transaction costs for consumers.

In reality, this is what happened:

Large retailers, many of which were on transparent cost-plus pricing models, saw their total cost of accepting payments reduce in line with the interchange fee reductions.

Small businesses did not immediately see a reduction in their processing costs, but over time, fees did reduce, mainly due to market competition.

Consumers suffered. Card issuers, now making less money per transaction, reduced the level of cashback and other card rewards they paid out.

The value of credit card rewards reduced in accordance with the reduction in interchange.

Before the IFR, interchange fees on credit cards were 0.8-1.6% (depending on the card type). When the 0.3% cap was instituted, the value of card rewards soon reduced by up to 80%.

Meanwhile, Amex was not affected by the interchange caps in the IFR.

Only so-called four-party credit card schemes were regulated.

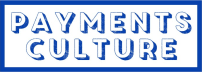

In the UK, Amex is both an issuer and an acquirer. As well as Amex, the other two parties involved in transactions are the merchant and the cardholder, making Amex a three-party scheme. Three-party schemes were explicitly excluded from the IFR.

On the other hand, Visa and Mastercard are considered four-party schemes. In each transaction, there’s the issuer, acquirer, cardholder and merchant. (Curiously, the card networks are not counted in the four-party model)

While Amex does charge businesses a fee to accept their cards, it’s known as the Merchant Discount Rate, or simply the discount rate. Amex’s discount rate is a single fee that cannot be broken into various components, such as interchange and scheme fees.

Post-IFR, Visa and Mastercard consumer credit cards could charge a maximum of 0.30%, but Amex cards faced no limit. The only constraint was what could be successfully negotiated with merchants. Amex does not publish its fees in the UK, but anecdotally speaking, Amex’s fees did reduce post-IFR. Large retailers especially were able to negotiate lower Amex fees. Generally, Amex transaction fees remain significantly higher than those for Visa and Mastercard transactions.

Amex justifies its higher cost of card acceptance through its positioning as a premium brand. Premium here means more affluent, higher-spending cardholders. The IFR has entrenched Amex as the premium choice that pays the best rewards.

The card rewards calculation

While we wait to hear more about Revolut’s credit card offering in the UK, Revolut has already launched credit cards in some markets. For instance, in Poland, Revolut offers a credit card with the following benefits:

Get 1% cashback on all card purchases for the first 3 months or until you spend 2000PLN, whichever comes first. After that, earn 0.1% unlimited for all eligible transactions.

(Note that 2000 Polish Zloty is approx £400, €470, or $540)

Users benefit from up to a 2000PLN cashback in the first three months, and then cashback is a consistent 0.1% after that. Notice that 0.1% is below the credit card interchange rate of 0.3%. So after the first three months, Revolut, as the card issuer, makes a consistent gross margin of 0.2% on every transaction.

The enhanced cashback in the first three months can be considered part of the customer acquisition cost. Most customers will not spend enough to get 2000PLN back as this would entail spending 200,000PLN or $54,000 in three months. If a cardholder spends that much, they are likely also using other products in the Revolut ecosystem and generating revenue in other ways beyond just cards.

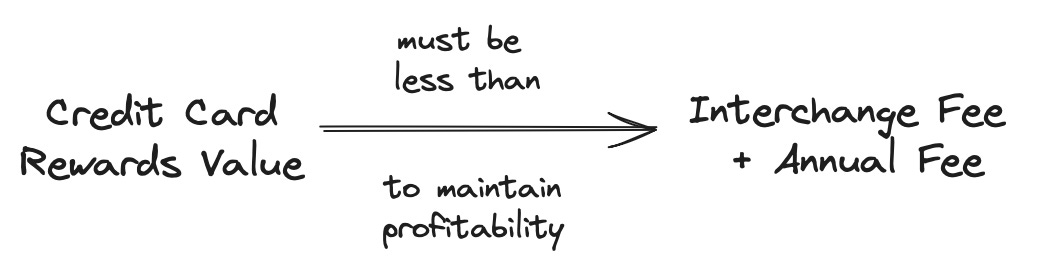

In an earlier post on this Substack titled How Credit Card Rewards Work, I wrote that interchange was just one component of the credit card business model. Other fees, such as annual or monthly fees, could also be considered when creating a credit card programme:

We can separate the business model for credit card companies into four distinct revenue streams:

A fixed annual or monthly fee, sometimes known as a membership fee.

Interest fees.

Interchange fees.

Ad-hoc fees, including foreign exchange fees, when a card is used abroad.

Annual or monthly fees and interchange are the most reliable income lines for card issuers. A large portion of customers pay off their bill in full each month and don’t incur interest. Income derived from interest on revolving balances can be lucrative, but also comes with the risk of credit losses and customer default. Fees on foreign currency transactions have historically been lucrative but now much less so.

Previously, banks would charge 2-3%, but competition has made this untenable as neobanks such as Monzo and Revolut charge zero foreign exchange fees.

At least in the UK market, following any short-term customer acquisition programme, card issuers tend to keep the rewards they pay below interchange fees. In some cases, the impact of monthly or annual fees may also be considered. On the other hand, in the US, rewards in excess of interchange are not uncommon. In such cases, companies usually realise additional revenue lines from the cardholder relationship.

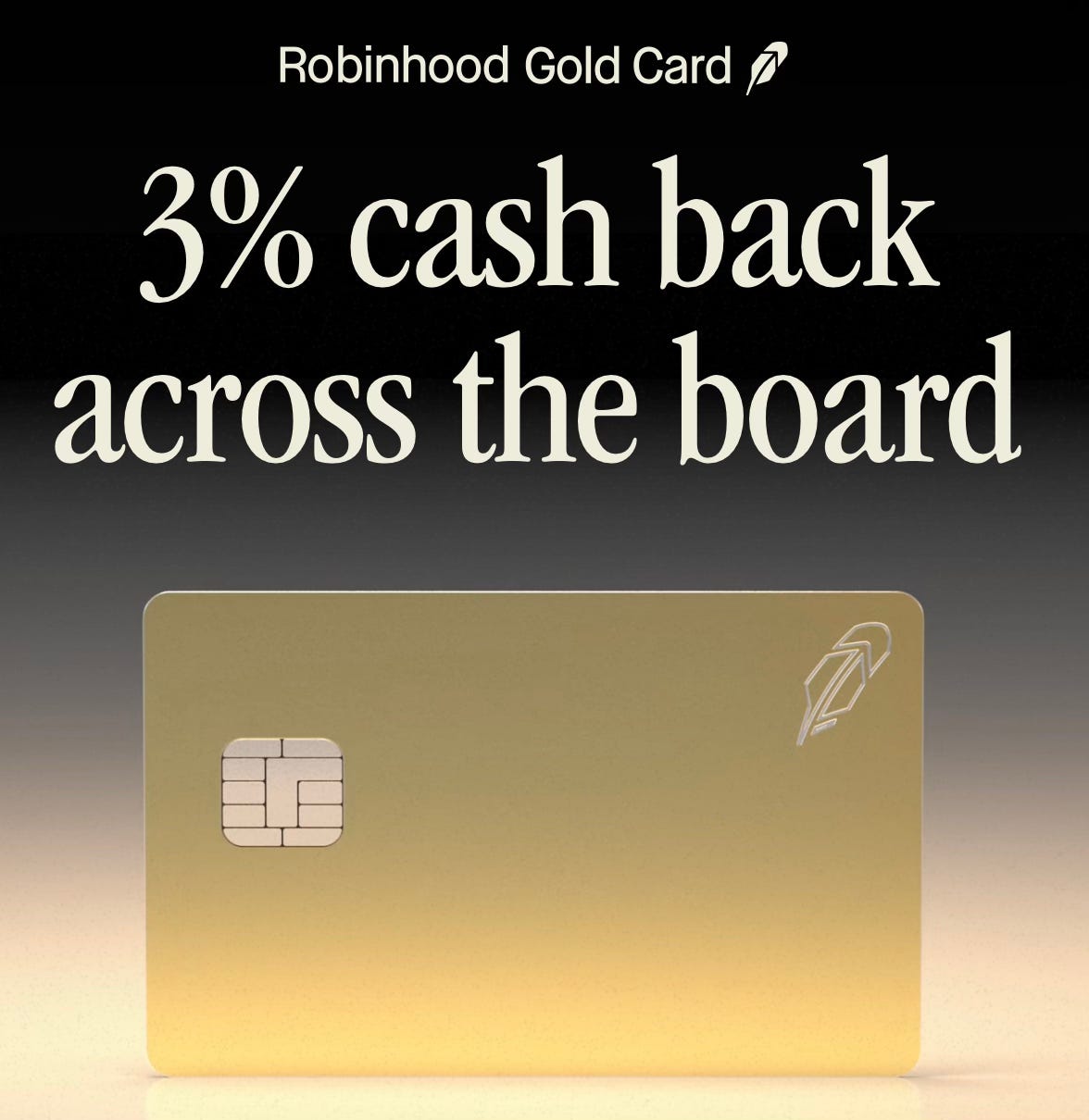

Rather than provide cashback or air miles, Revolut’s rewards offering in the UK will utilise their own points system, called RevPoints. The Sifted post mentioned at the start of this post noted:

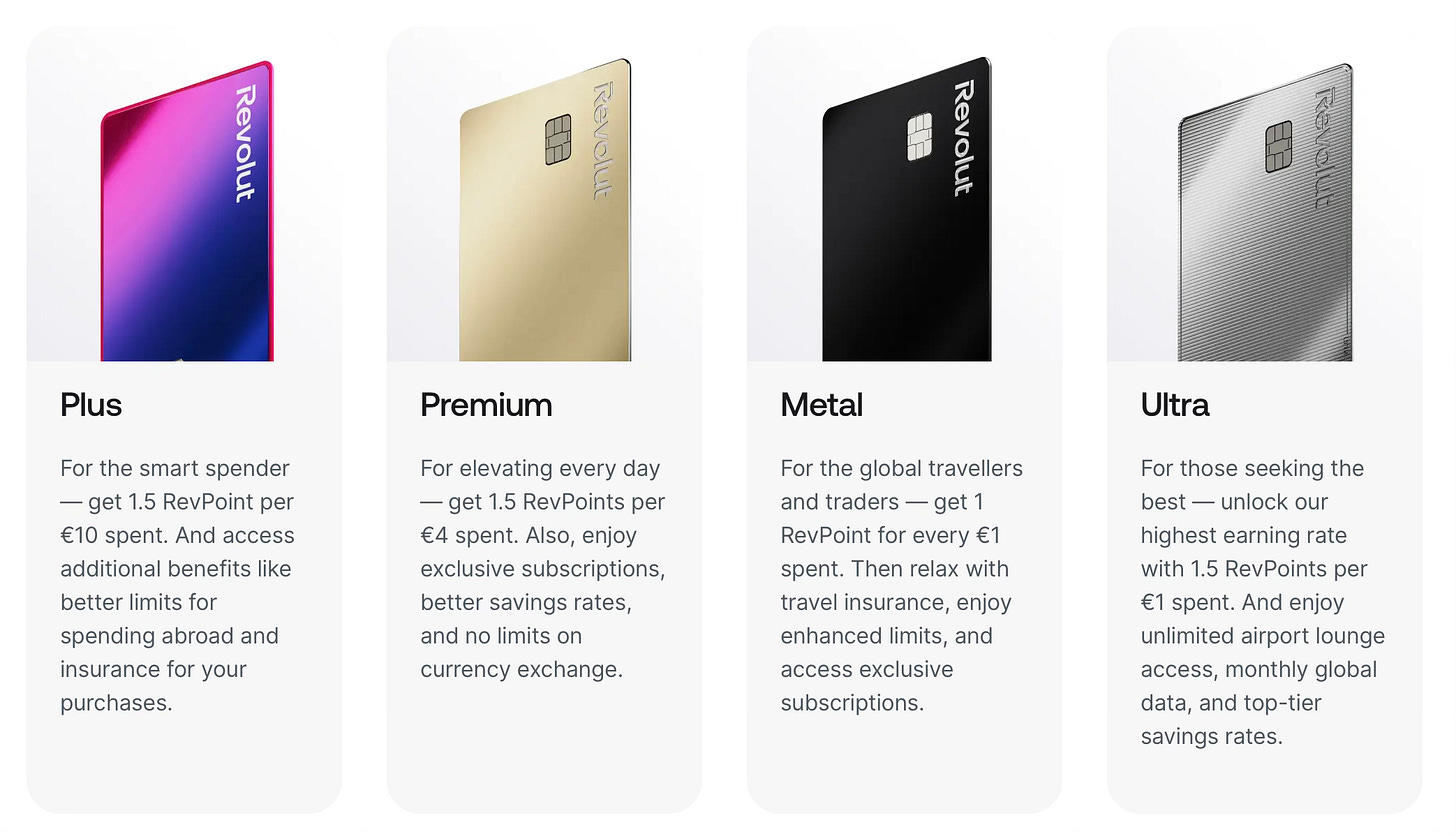

Revolut users currently earn RevPoints by making purchases on their debit cards. Two sources familiar with the plans say Revolut intends to build a set of points-based credit cards for each of its subscription tiers.

In fact, Revolut has already launched a credit card based on RevPoints in Ireland. The UK offering will likely follow the same broad approach as the card launched in Ireland, which offers different levels of RevPoints based on a user’s membership plan. The more expensive the monthly membership tier, the higher the RevPoints earned by a user’s card spend.

Revolut has 3 million customers in Ireland, 75% of the adult population. The neobank has more customers than any traditional bank in Ireland, making Ireland a solid testing ground before launching in the UK.

How credit card strategy is evolving

After looking at how card rewards work, we can answer the question posed in the title of this post. The answer is that, quite simply, Revolut cannot compete with Amex on a like-for-like basis when it comes to credit card rewards. The IFR (Interchange Fee Regulation) gives Amex a competitive advantage over Visa or Mastercard cards, which can’t be overcome on a single-product basis.

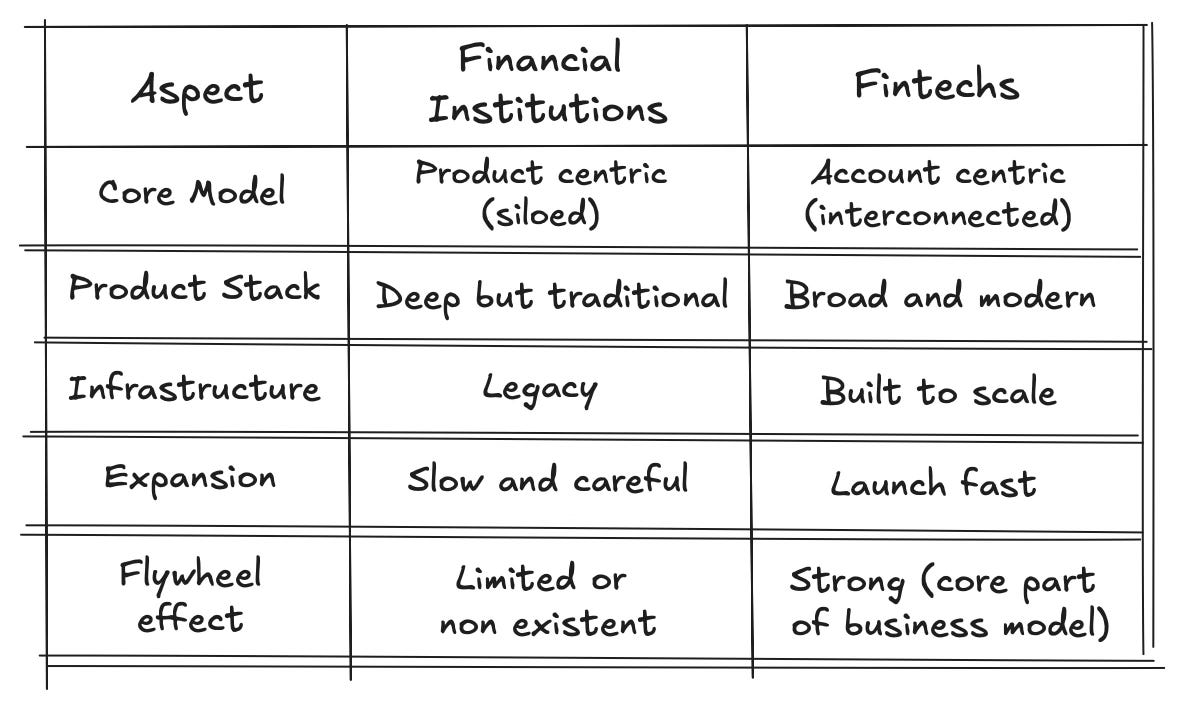

What needs to be understood is that Revolut is not looking to compete directly with Amex. Revolut’s strategy is quite different. Looking beyond credit cards as a standalone product. Instead, credit cards are one aspect of an expanding flywheel of financial services.

While Revolut may be the best example of an ever-growing-global-financial-flywheel, they are not the only one operating in this way. In the UK, as well as Revolut, Monzo, Yonder, and Curve are all neobanks or fintechs that are building out an ecosystem of financial products, which can expand as strategy determines, both into new product areas and to new markets.

The fintech model contrasts with the traditional business model of most legacy financial institutions. Many banks have simplified their product lines and sought to make each product self-sustaining within its own business area. Partly, this was due to regulation. In some cases, banks were limited from bundling products due to competition concerns. In other cases, banks made the strategic decision to focus on their core offerings.

Prior to the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC), some banks had sprawling empires across a wide range of products and geographies. Take for instance, the Royal Bank of Scotland, now known as Natwest. At its peak, the bank operated in 53 countries, but nowadays, outside of investment banking, it operates solely in the UK and Ireland.

It’s been a consistent story across the banking sector since the GFC. Banks have sought to focus on their home markets and a limited number of product areas. After the tumult of the GFC, this stable growth was sought by regulators, but it has opened banks up to competition from fintechs who grow within a different paradigm. Fintechs build out their financial flywheel and nibble away at what legacy financial institutions offer.

With Amex, their offering in the credit card rewards space remains strong. Regulation has helped Amex cement a unique position in the UK and wider Europe. While they have a regulatory advantage, they will continue to do well as the best standalone rewards card. But if any future interchange regulation does impact them, then their strategy may need to change.

Today, while Amex attracts customers who prioritise maximising the level of rewards per transaction, Revolut’s ecosystem model appeals to users seeking a wider set of financial products in an intuitive ecosystem. Many people like to use both, and why not?

Note that views expressed on this Substack are my own and do not represent any other organisation. Also nothing I say should be taken as investment advice.