Does the Visa and Mastercard settlement really matter?

Interchange fee reductions don't always benefit everyone but some win big

Recently, the big news in payments was the settlement that Visa and Mastercard reached with a group of merchants in the United States. The case originated as a Class Action Complaint on June 22nd, 2005. The Class Settlement Agreement of March 25th 2024, brings the case to a close - at least for now. (A class action lawsuit allows various parties to come together to make a case on behalf of a larger group.) The result was a series of changes to the fees businesses pay for accepting card payments. Reuters led with the headline Visa, Mastercard reach $30 billion settlement over credit card fees. $30bn is a significant number in anyone’s book, but $30bn did not change hands here. So what is the actual impact, and does it matter?

I’m not going to re-cap every detail of the case. (Some valuable sources on the case can be found in the financial media, including the Financial Times, The Wall Street Journal, and Bloomberg. Some valuable LinkedIn posts on this topic are from Christopher Uriate at Glenbrook, John Drechny from Merchant Advisory Group, and Flagship Advisory Partners. On X, as usual, there’s been some excellent analysis, particularly from Scott Wessman - part 1, part 2.) Instead, in this post, you’ll find some observations, especially regarding the interchange fee reductions within the settlement agreement and the potential impact on credit card rewards.

Originally, I wrote another section at the end of this post on the impact of the settlement agreement on surcharging. But upon reflection, it seemed to duplicate much of what is written elsewhere with little added value. So please take a read of some of the links above if this area is of interest.

Interchange Regulated

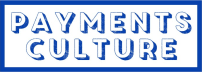

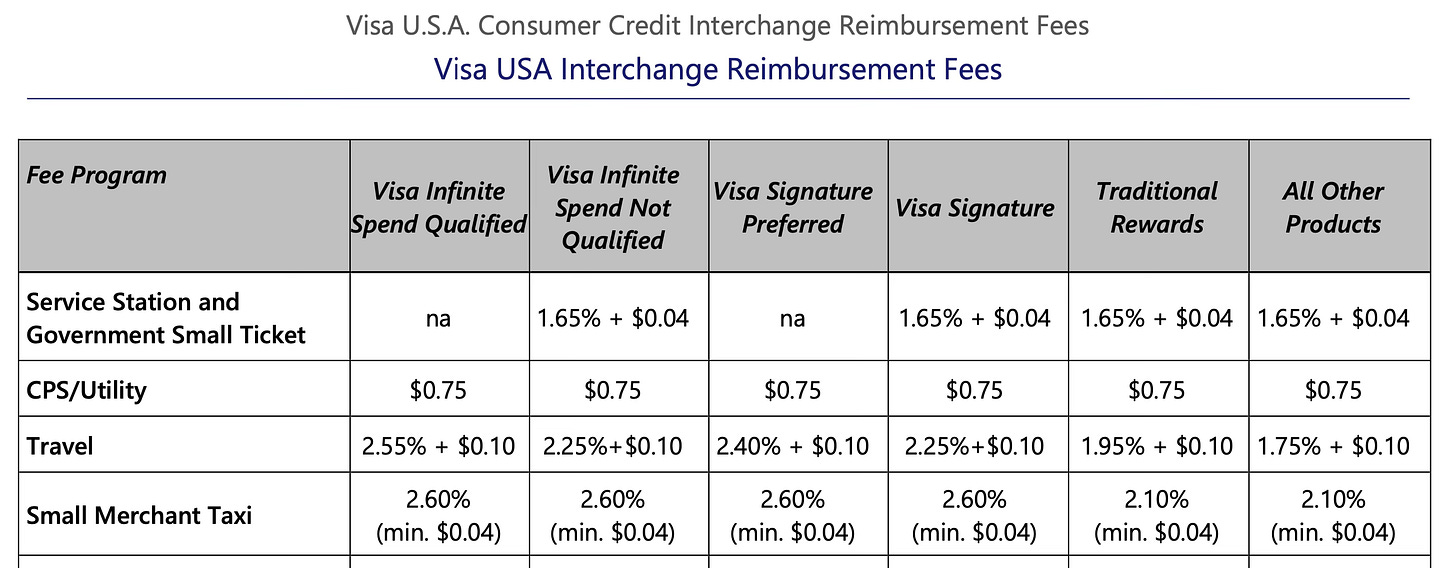

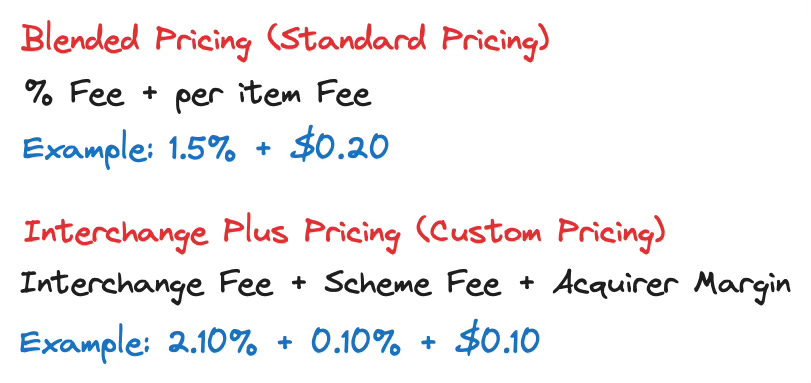

A crucial part of the settlement is the regulation of interchange fees. Interchange fees are often described synonymously as swipe fees in much of the media reporting on this story. The settlement agreement itself doesn’t use the term “swipe fees”. Instead, it mentions “swipe/dip/tap”, reflecting that cards are often not only swiped these days. Cards are dipped when reading the chip and tapped for a contactless payment. Interchange is just one part of the total fee incurred when a payment card is used, albeit the largest part. The other elements are network fees (scheme fees) and markup applied by the acquirer. In some cases, the acquirer may be represented by a payment processor. The acquirer charges and collects all the fees, keeps their markup, and distributes the rest to the other parties.

Only the interchange element of the total credit card processing fee is mentioned in the settlement agreement. There’s a mandated reduction in interchange fees for credit cards of at least 0.04%. This required reduction of four basis points is the Posted Interchange Rate Reduction (PIRR), and applies to all credit card interchange fee types and categories. I mention “all fee types and categories” as interchange fees are not straightforward. From an earlier Payments Culture post on the topic of credit card rewards:

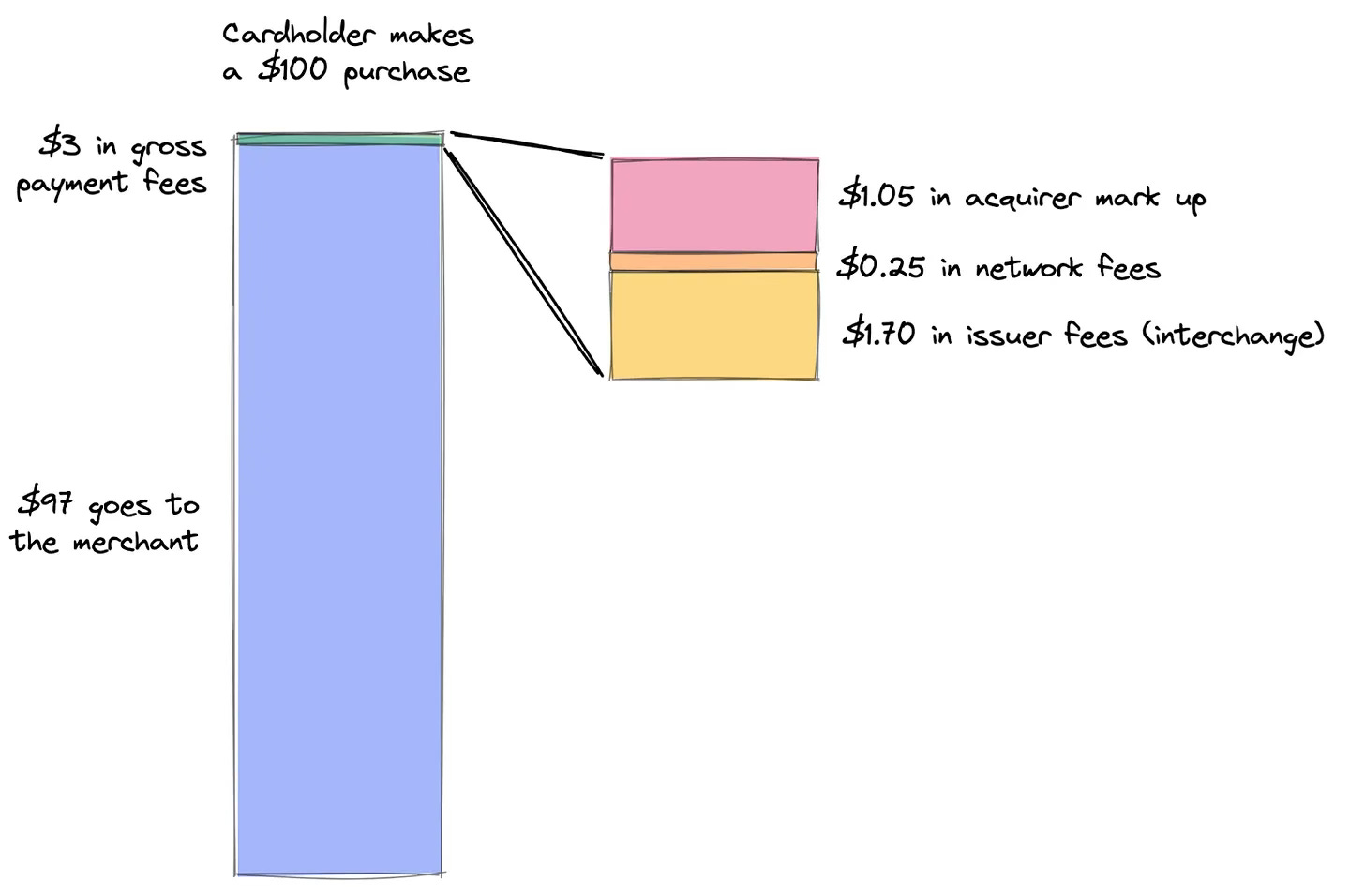

Interchange fees are complex [in the United States]. The full range of interchange fees are publicly available on the Visa and Mastercard websites [and] differ based on the type of business the card is used at, and the type of card itself.

For instance, on a Visa consumer credit card, interchange fees can range from 2.10% to 2.60% when used at a restaurant. When cards are used at a supermarket, interchange fees can from 1.15% with an additional flat fee of $0.05 up to 1.40% with an extra $0.05. Different sectors incur different fees.

If a card offers little or no rewards, then the interchange fee will be at the low end. Cards that offer the highest rewards will incur an interchange fee at the high end.

In addition to the minimum four basis points reduction that needs to be applied to all credit card interchange fee rates, the settlement also contains a seven basis points reduction in what is called the Average Effective Rate Limit (AERL). Therefore, whilst each interchange fee category must be reduced by at least 0.04%, the average overall fee reduction must be at least 0.07%. If some fee categories are only reduced by 0.04% then others will need to be reduced by more to make the reduction across the board equivalent to 0.07%.

Even though the settlement was only reached a short time ago, Mastercard has since announced an increase in scheme fees. They will rise from 0.13% to 0.14% from April 15th, bringing Mastercard in line with Visa’s network fees in the US. Unlike interchange fees, scheme fees are not published and tend to be more complex in how they are calculated. The headline rate of 0.14% mentioned above is likely an average of various rates applied. Schemes fees rising so soon after last week’s settlement shows one of the flaws of the settlement. Only interchange was addressed. The scheme fee component wasn’t mentioned. So whilst interchange has been addressed, nothing in the settlement stops network fees from rising.

It’s worth referencing a recent experience of regulating interchange in Europe. In January 2016, The Payment Service Directive 2 (PSD2) capped interchange rates in European Union (EU) countries. The cap was 0.20% for debit cards and 0.30% for credit cards for most cards. (Despite leaving the EU, the UK still adheres to these caps.) Since then, scheme fees have crept up, yet as they are not published, it’s hard to put a direct cost on any increases. It’s safe to say that any rise in scheme fees has been slight compared to the reduction in interchange fees from the regulation. Across the board, interchange was reduced by an estimated 1% or more across all markets.

Rewards Impacted?

Reducing interchange in Europe was supposed to lower consumer prices, but it did not. In some cases, retailers absorbed the cost reduction as extra profit - at least in the first year. And consumers didn’t benefit. In many ways, consumers suffered.

Reducing interchange fees led to the slow dismantling of many credit card reward schemes in Europe. Credit card rewards are primarily funded by interchange revenue. Since 2016, the ability to get a credit card with high rewards - such as cashback or points - has diminished dramatically in the UK and the EU. For one stark comparison, Robinhood now offers a card with 3% cashback, whereas in the UK, one of the leading credit card issuers, Barclaycard, offers just 0.25% cashback.

On one hand, this makes total sense. If the interchange fee is 0.30%, the cashback offered should be below this level for the programme to be profitable. On the other hand, the average interchange rate in the US is around 2.2%, but Robinhood is offering cashback of 3%. So it’s easy to think that this product must be a loss leader, as the cashback is significantly above the interchange fee revenue. However, there are other revenue streams that card programs can generate over and above interchange, such as interest from those who don’t pay off their balance each month.

Lex Sokolin has pointed out that the Robinhood card isn’t as straightforward as it seems. And it's very much a customer acquisition strategy for their brokerage (share trading) business:

Advertising this as a "no fee" card is misleading. To qualify, users subscribe to a Robinhood Gold account, which runs $5 per month or $50 per year.

The cash back has limitations as to how it can be redeemed — (1) purchases at select merchants directly through Robinhood’s shopping portal; (2) booking travel through the travel portal; or (3) redeeming as cash to be deposited in the Robinhood brokerage account, which is set up automatically

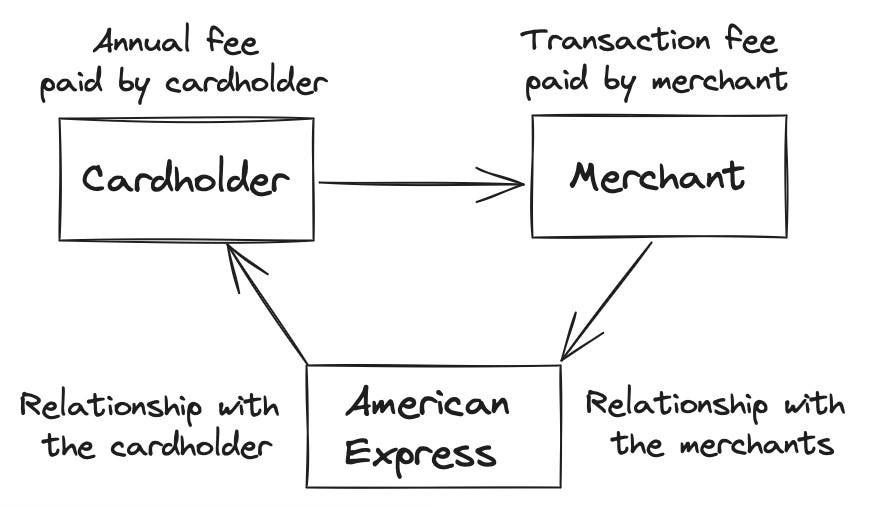

While Robinhood may not offer cashback in the most straightforward way, it’s indicative of the competitive environment. American cardholders can enjoy a high level of rewards and cashback, but European cardholders have to make do with little or no rewards - unless they get an American Express card. Only the so-called four-party payment scheme model was regulated in Europe, which is what Visa and Mastercard fall under. American Express usually takes the form of a three-party payment scheme, which is not regulated in the same way in Europe.

Note: Just before I published this post, news broke of major changes to one of American Express’s leading cards in the UK. The British Airways American Express Credit Card and the Premium Plus version are very popular due to the 2-4-1 British Airways voucher, which can be obtained if the annual spending requirement is met. Cardholders will see their spending requirement rise from £12,000 to £15,000 for the free card and from £10,000 to £15,000 for the Premium Plus card (which will also see its annual fee rise from £250 to £300 per annum). Despite this, American Express offers far better rewards than other competitors.

Interchange regulation means that it’s the only game in town when it comes to high-value rewards cards. Perhaps not by design, but by regulating three-party, but not four-party card schemes, American Express has a dominant position in this particular customer segment. I anticipate most customers will remain despite these changes.

In the United States, credit card issuers will make less revenue from interchange as the rates decrease. All things being equal, cardholders should see either a slight increase in their annual fee(s), or a small reduction in their rewards. But in a market where issuers offer high levels of rewards, a drop in interchange revenue of seven basis points will barely make a dent.

Some companies may choose to adjust their pricing models. Mainly if they are banks with a policy of ensuring all product lines are profitable. However, those card issuers operating at the ultra-competitive top end may need to decrease their margin and absorb the hit of the interchange reduction to maintain market share. In other cases, companies may treat interchange revenue as a path to cross-subsidise other revenue streams (as per Robinhood example).

Who Benefits?

Whether businesses benefit from the interchange reductions depends on one key factor. That is, the pricing they have in place with their acquirer. There are two main models utilised. Small businesses usually get a take-it-or-leave-it pricing model. There’s a percentage fee and sometimes also a per-item fee that applies to every transaction. Pricing is usually set for the duration of a contract, and has to cover the interchange and scheme fee costs and build in margin for the payments processor.

Large merchants are usually on a custom pricing model which transparently splits out the various fee elements. This model's acquirer margin is fixed per item ($) or as a basis point margin (%). Usually, the margin is fixed for several years, and any changes in the other costs are passed directly through. As you can guess, large businesses automatically benefit from interchange fee reductions. But small businesses may not get any of the reduction in interchange fees at all.

So despite the reduction in interchange fees, small businesses may see none of the benefits. Top-tier merchants on custom pricing models may see millions of dollars worth of savings. There may be a competitive space here for suppliers to compete on price in the SME market. The settlement agreement has definitely generated awareness in the market, and a greater degree of transparency may now be expected.

If you enjoyed reading this post, you can connect with me on LinkedIn, X, and BlueSky.