Disclaimer: views expressed here are my own and do not represent any other organisation

This is a two-part series on neobanks. Part two will follow early next week and examine the differing strategies of the big three UK neobanks.

Update: part two can be found here.

Good times for neobanks

Neobanks have had a good few months. In May, Brazilian neobank Nubank announced that it had reached 100m customers. The 100m customers sit across Nubank’s three operating markets, with 92m in Brazil, 7m in Mexico, and 1m in Colombia. It took Nubank just 11 years to go from launch to 100m customers, and it is adding over 1m new customers a month in Brazil alone.

Rupak Ghose has called Nubank the gold standard in fintech neobanks, noting that its Q2 results, announced in mid-August, saw revenues rise 65% year-on-year to $2.8bn. 60% of Nubank’s customers use it as their primary bank account, an impressive statistic given with neobanks there’s always the risk that users create an account but don’t use it day to day.

In addition to the growth in revenue and customer numbers, a key strategic partnership was recently announced between Nubank and Wise. Wise will work with Nubank to offer international payments and to allow Nubank customers to hold balances in USD and EUR, all via the Nubank app. Nubank has been an amazing success story. The company was listed on the New York Stock Exchange in December 2021, and at the time of writing at the end of August 2024, its market cap is $71bn, and its share price is up over 70% year to date.

Back in the UK, arguably the most significant story in the world of neobanks was Revolut getting their UK banking license. The licence does come with restrictions, such as only being able to take £50,000 of deposits per customer, but these restrictions are expected to be lifted in due course. The original licence application was submitted back in 2021. This three-year approval process is much longer than the average of around a year that other banks have usually taken.

For Revolut, getting their banking license was a long journey. Some argue they should have started their application earlier, back when the company was smaller. Even back in 2021, Revolut had 16m customers, and when financial institutions grow, their compliance burden increases.

Until its banking licence was approved Revolut had operated as an e-money institution. An e-money licence allows financial institutions to offer a pre-paid account with a linked debit card. Before allowing an institution to step up, regulators probe whether an organisation’s compliance and risk functions can operate at the level and scale expected for a bank. During the application process, Revolut went back and forth with the UK regulator, until Revolut CEO Nik Storonsky got a letter from the Prudential Regulation Authority confirming the application had been successful.

The UK banking licence is of particular importance to the company. Revolut may have got their EU banking licence first, but the UK is the market where Revolut began, and of Revolut’s 45m global customers, 9m are in the UK. Getting a UK licensc is seen as a sign of credibility. Future licence applications for markets such as Australia and even the US could follow, with work underway to expand its solutions in India.

The recent good news had been fruitful. Revolut was recently valued at $45bn. Large institutions, including those who had previously invested in Revolut, are looking to buy shares from staff.

Revolut has clinched a $45bn (£35bn) valuation through a share sale that is expected to net staff a $500m windfall, cementing its position as the most valuable private tech company in Europe.

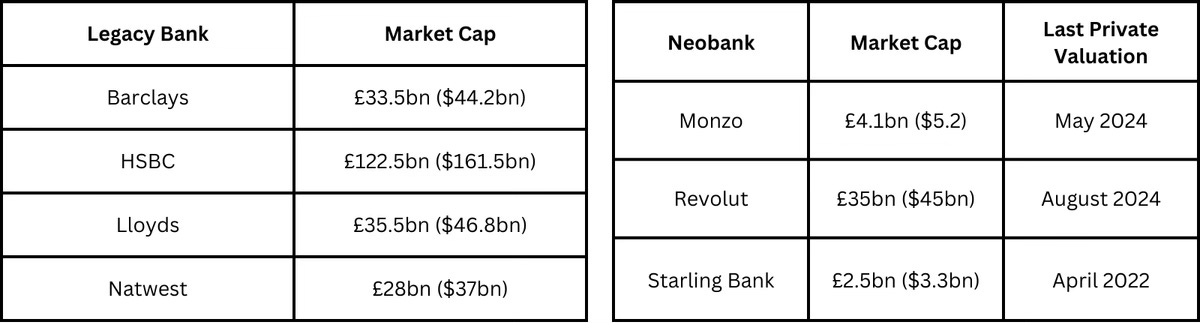

It is a boost for the London-headquartered firm, which was last valued at $33bn in 2021. It is now worth more than the market valuations of big high street banks, including NatWest and Barclays, which are worth £29bn and £33.5bn, respectively.

Alongside Revolut, Monzo and Starling Bank - referred to as just Starling from now on - make up the UK’s three main neobanks. All were founded within approximately a year of each other in the summer of 2014-2015. Monzo and Starling’s valuations are more modest than Revolut’s, but still an impressive $5.2bn (£4.1bn) and $3.3bn (£2.5bn) respectively.

Note: Starling hasn’t been valued in the private market since 2022. They reached profitability faster than the other two and didn’t fundraise as often, hence the lack of recent valuation.

The difference with neobanks

Neobanks can be contrasted with legacy banks. In the UK, the big four legacy banks are Barclays, HSBC, Lloyds, and NatWest, some of which have a history that can be traced back hundreds of years.

In the past ten years, neobanks emerged and transformed the banking landscape in the UK. These companies were formed out of frustration with the way banking was done. Consumers were using smartphones more and more in everyday life, yet banking was still painful on mobile. Banks seemed to be stuck in their old ways. That was all about to change.

Neobanks operate on a few key tenets:

Mobile first

Most neobanks offer their services only on smartphones. They don’t have physical branches, and most offer minimal - if any - options for banking on a laptop or desktop computer. On the other hand, legacy banks still maintain large branch networks. When branches close, there’s pushback from local communities. Many people, such as older adults, prefer, or even rely on physical branches for their banking. Maintaining these branches is hard work and expensive.

A recent estimate by CBA, an Australian bank, estimates that the cost of keeping its branches stocked with cash is A$350 (£180m; $237m). Some years ago, someone working at a large UK bank mentioned that running the branch network cost over a billion pounds per annum. These are no small sums that could go straight into investing in technology or to a bank’s bottom line.

Rapid account opening

Neobanks offer the ability to open an account often in just minutes, provided you have the right ID on hand, such as a passport or driving license. A user will need to take a photo of their ID with their smartphone during the account opening process. This has been a significant change. It wasn’t long ago that banks required prospective customers to bring a copy of their physical ID into a branch to open an account.

Improved UI/UX (User Interface and User Experience)

Neobanks started with the premise that banking could be much better. Quite simple yet powerful improvements to mobile banking UI/UX were soon made. Many of these are now standard across all banks, yet for a while, they were exclusive to neobanks.

Some examples include:

The ability to cancel a debit card and order a new one straight from a mobile banking app, for instance, if a card is lost or stolen. Previously, this would have required a phone call and a long wait on hold to a bank’s call centre.

The ability for users to immediately receive in-app notifications when spending on a debit card, including notification of the amount and name of the merchant. This helps keep track of spending on the go rather than seeing the transactions at the end of the day.

The ability to see debit card details such as PIN number and full card number in-app. Previously, forgetting a PIN number meant waiting for a new PIN to arrive in the post. Those times are over. Now, the PIN number can be seen in app. Face ID or a similar biometric allows the user to see the PIN.

The points noted above are both functions of doing something better or not needing to do something at all, such as not needing to maintain branches. Neobanks’ competitive advantage came from understanding how a mobile-first world would transform banking and delivering on that vision. They recognised that smartphones were becoming central to people’s lives and designed their services accordingly.

For a long time, as their core offering, banks provided current accounts (sometimes called checking accounts), loans, savings, mortgages, and credit cards. Some banks served only personal account holders, while others also offered solutions for small businesses and large corporate clients.

Additional products that banks may offer could be wealth and investment management solutions, private banking, and even adjacent solutions such as insurance. Sometimes, banks may sell these solutions, but they are serviced by specialist third-party providers, especially with insurance products.

Let’s put it in the context of fintech. I think the first iteration of fintech was taking certain parts of the value chain—international payments, whatever—and doing it better than the banks, at a lower price. The big banks can respond just by dropping their price, and then you’ve got fintechs addressing the underserved at high cost. But Starling is going head-to-head with the big banks for their principal customers, with a different cost base. And that dramatic difference in cost base allows you to take market share and improve service.

The conversations on the boards of big banks have changed from “We’re worried about these fintechs taking a bit of our business” to “They’re actually competing head-to-head for mainstream business.” Anne Boden, Starling Bank founder

Fintechs succeed initially by building a wedge. That is, focusing on one specific use case in which incumbent players provide a poor customer experience and charge high fees. Fintechs make sure they can do this one function much better than incumbents. Alongside this, successful fintechs, especially those in the B2C segment, work on developing a community and interacting with users to garner feedback. As the original initial use case succeeds, a loyal and engaged user base can then move with the company into new product areas.

Neobanks were no different. The big three UK neobanks started by offering 0% Foreign Exchange (FX) fees when spending abroad. There were 86 million overseas trips by UK residents in 2023. British people like to travel. We prioritise taking a summer trip to Spain, Portugal, or these days even Turkey - our weather is too unpredictable to rely on for a staycation. Once consumers understood that their bank was charging them around 3% for transactions in Euros, Dollars or Lira and that better options were available, many consumers gave Monzo, Revolut or Starling a try and liked what they saw.

Building a wedge and then?

This is where it gets interesting. From building the initial wedge of 0% FX coupled with a much better UI/UX than existing banks, the three leading UK neobanks then followed different paths. All three have had, and still today have, their own unique blueprints for growth. While legacy institutions often follow similar, well-established patterns and ways of working, neobanks have differing business models. These differences are part tech and part culture. In part two, we’ll look at the growth strategies of the UK’s three main neobanks - Starling, Monzo and Revolut.

If you enjoyed reading this post, you can connect with me on LinkedIn, X, and BlueSky.

Great article, interesting takes and comprehensive coverage!

It’s also great how neobanks broaden potential customer base, acquiring and banking individuals that were under/unbanked by incumbents. I remember waiting 2 months in one of the Vienna’s banks to get an account. But then with Revolut I’ve got another one within 30 minutes, instant experience lift

Very interesting! Well done, Matt!