Blik and you'll miss it

The unstoppable rise of modern Poland (and its mobile payments)

Welcome to Payments Culture!

I’m currently looking for new opportunities. I’m open to short-term assignments as well as permanent positions. You can email me or contact me on LinkedIn to discuss further.

Donuts. It’s probably not the first thing that comes to mind when you think of Poland.

But Polish donuts are delicious.

Pączki is their local name, yet most people know what you mean if you stick to saying Polish donuts.

Pączki are not gloopy like traditional British jam donuts and aren’t as sugar-coated and iced to the max like Krispy Kremes. I devoured one and a half of these tasty treats sitting in a park in Gdańsk at the end of August. (The first half I’d eaten walking from the store to the park. I couldn’t wait to taste it.)

My Ryanair flight — that I mentioned in my last post — had taken me to the north of Poland for a late summer vacation.

On my third day in Gdańsk, I found a branch of Dobra Pączkarnia. A specialist bakery that sells only one thing. Polish donuts. This branch was a mere small counter facing the street with no seating area. The line was relentless, snaking around the block with families, young couples, and dog walkers all waiting for their pączki. The donuts came out fresh from the oven and into customers’ hands within seconds. Yet despite how quickly each new batch of donuts was snapped up, the queue never seemed to shrink.

Dobra Pączkarnia describe their product as:

Fluffy, delicate dough, an excellent shape, and a richly filled interior

(puszyste, delikatne ciasto, doskonały kształt, jasna obrączka i bogato nadziane wnętrze)

If that doesn’t already sound tasty then how about the flavours to whet your appetite? Everything from apple & cinnamon, pistachio, and Nutella, to custard, salted caramel, and forest fruits. Of course, you can’t try all the flavours on one day, so if you’re ever in Gdańsk — or anywhere else in Poland — you’ll have to return to a Dobra Pączkarnia shop another time to try more flavours.

Polish donuts have existed in some form for more than five hundred years. Local food traditions remain, and even when history is turbulent, home comforts often survive into the modern day. As ever, with continuity, also comes change. Poland has been successful in balancing tradition with massive political and economic transformation.

A catalyst for this turning point was Poland’s membership of the European Union, which led to new opportunities, both at home and abroad for Polish citizens. Since joining in 2004, Poland’s GDP per capita has more than doubled. Economic growth has been the third-fastest in the union (behind only Malta and Ireland).

Joining the European Union meant newfound freedom of movement, and many Polish citizens moved to other countries, mainly for better job opportunities. By 2016, over one million Poles were living in the UK. In the nine years that followed much has changed.

In today’s Poland you rarely see litter on the streets, and crime — or at least the perception of crime — is low. Poland has garnered a reputation as a nice place to live, and while many in the UK feel like living standards have stalled, in Poland there’s optimism and the feeling that things are ever improving. Many Polish citizens have moved back home in the years since 2016.

This is not said to talk down the UK, but the newspaper headlines of England being inundated by Polish plumbers are long gone. Some British nationals — even those without family ties — are now trying their luck living in central Europe. The tables have turned somewhat.

Gdańsk is the largest city in Northern Poland. Walking around the city centre you can’t miss the recently built sleek glass-fronted apartments that line the walkway along the river. The area bustled with crowds of both tourists and locals, and boats meandering downstream. Vibrant cafés with crowded outdoor seating completed the scene — all clear signs of economic dynamism.

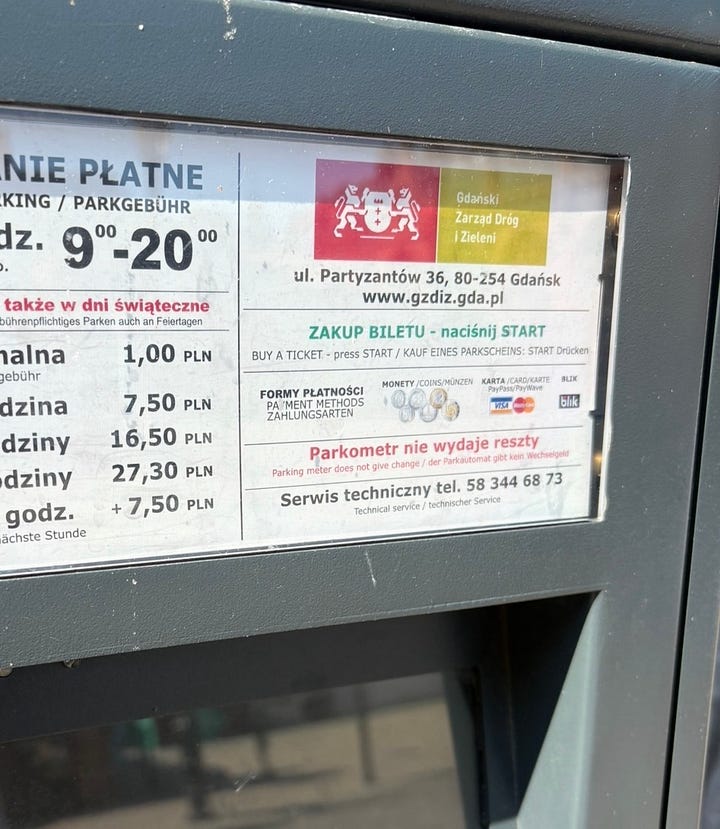

This was my first trip to Poland since 2017. Back then, even though I could use my credit card in most places, I had to use złoty cash on some occasions. But on this trip, cashless payments were everywhere. There was only one occasion on my week-long trip when I needed to go to an ATM for cash, and that was to pay at a market stall. Other than that, cards could be used everywhere. More importantly, BLIK was everywhere.

BLIK is Poland’s leading non-card payment method. It emerged from a collaboration between Polish banks in 2015 and is one of the best examples of branded A2A payments. BLIK was on every POS device I saw in Poland, and can even be used to withdraw cash from an ATM — in lieu of inserting a debit card.

Other comparable models to BLIK in other markets include Swish (Sweden), Vipps (Norway), and Twint (Switzerland). Each of these mobile payment systems operate on instant payment rails, which means payments settle within seconds, whereas card payments usually settle the next day.

BLIK has some specific elements that make it unique. Each transaction at an ATM or in-store purchase needs a 6-digit BLIK code — the code is generated on the user’s mobile device within the banking app and entered on the POS. When it comes to ecommerce payments, trusted stores do not require a BLIK code, making checkout fast and seamless.

Since launching in 2015, BLIK’s growth and development have been remarkable:

As early as 2018 BLIK was available as a payment method in two of Poland’s largest supermarket chains — Biedronka and LIDL.

International payments firms such as Stripe, Adyen and PPRO all support BLIK as an ecommerce payment method, showing that when selling to Polish businesses offering BLIK is absolutely essential.

The most important sign of BLIK’s success is the sheer volume of transactions processed. By the end of 2023, BLIK was the largest branded A2A payments system in Europe. BLIK saw more transactions (1763 million) than both Swish (977 million) and Vipps (531 million) combined, which are near ubiquitous payment methods in Sweden and Norway respectively.

As I don’t have a Polish bank account, I was unable to use BLIK to pay for my donuts. But seeing so many locals use BLIK got me thinking, why has it succeeded, and what can we learn from it?

Co-operation between banks in establishing BLIK was key. This allowed for a shared goal in building a domestic mobile payment system. The banks who didn’t join initially came on board later once they saw BLIK’s success.

Timing matters when bringing banks together. BLIK emerged when Poland’s economy was surging and on its path to becoming a cashless economy. By contrast, in the UK, banks collaborated on a similar scheme called Paym, but it emerged when cards were already entrenched and banks saw competition, rather than collaboration, as the main imperative. Paym was shut down in 2023 after ten years of largely unsuccessful operation.

BLIK benefited from instant payments from day 1 — via a payment rail known as Express Elixir. Compare this to the Eurozone where some banks still do not provide instant payments as standard for Euro transactions. Sitting outside the Eurozone has given Poland more autonomy and more flexibility. Having instant payments from the get-go meant banks could deliver the best possible user experience.

At the same time, BLIK, much like modern Poland, found its own path. The 6-digit BLIK code must be entered on a physical POS and is valid for only two minutes, after which the code changes. This is a unique solution. Most similar mobile wallets require in-app authentication or scanning a QR code.

My thoughts upon leaving Poland were of a country balancing tradition and modernity, and looking to the future with confidence. BLIK emerged from Poland’s transformation and is now a clear leader in European mobile payments. Other countries and payment systems can learn a lot from its success. In the blik of an eye, it’s grown to become one of Europe’s most intriguing fintech success stories.

Thanks for reading Payments Culture!

Please leave a comment or share with a friend or colleague if you enjoyed reading this edition. It’s much appreciated and helps grow the audience of this newsletter.

Note that views expressed on this Substack are my own and do not represent any other organisation. Also nothing I say should be taken as investment advice.

Great article, Matt. I love how you use your personal experiences to explain the world of payments. It takes us out of theory and makes everything concrete and easy to grasp.

Great Article and Title Matt. This reflects my experience working with and seeing Blik in the real world. I had always wondered how to write about the share scale of the progress they made, and over indexed on the complexity. Who knew making it about donuts was the perfect way to tell the story. Now will start telling Fintech travel tales from the POV of sampling the local cuisine.