Dollarising the world — coin by coin

The rise of stablecoins and the startups poised to capitalise

Everyone wants dollars. Some may argue that gold and Bitcoin are, like the dollar, universal currencies, but these are better as a store of value and not as a means of payment. (I wrote this before the recent Bitcoin crash!)

You tell me: If you were in Mexico City, would you rather have a crisp $50 bill in your pocket, or try to explain to your taxi driver how to set up a Bitcoin wallet? As a means of payment nothing comes close to US dollar bills.

Almost anywhere in the world, businesses accept dollars for goods or services (surprisingly you can pay with dollars in North Korea). Even if officially you can’t pay with USD in-store in many countries, unofficially, everyone knows it’s the currency that’s easiest to exchange, and whose value is universally recognised.

But go to any stablecoin event, and you’ll notice how most founders focus on the technical feat - moving money on-chain or from wallet to wallet. There’s a deeper story yet to unfold. Let’s consider that, at least so far, the story of stablecoins is the story of digital dollars. And the dollar itself, whether physical or digital, is the de facto global currency.

Stablecoins gained acclaim in 2025 as a means of moving dollars around the world at low cost. Yet we are in an era of shifting paradigms of money, where a maelstrom of forces intersect and the outcome is unknown. The next years will see the bifurcation of money unfold at breakneck pace — it’s a split between private and sovereign (government) money. How you're affected depends on your geography, and what's in your (digital) wallet.

In geopolitics, analysts often talk of a move from a unipolar to a multipolar world. A world in which US dominance is met with a spate of rising powers.

Writing in a recent edition of Wired UK, economist and author Keyu Jin states that “2026 will be the year when the US dollar dilution starts to build momentum”, and economies in the BRICS bloc are working on schemes such as mBridge and BRICS Pay, which bypass the current US-led financial system.

But according to Helen Thomas “it’s one thing to want the dollar to be less important and another thing for the dollar to be less important” (emphasis mine). Stablecoins may have something to say about this so-called dollar dilution. Measured by market capitalisation US dollar stablecoins account for nearly 99% of the stablecoin market. Despite their role as private money — as opposed to central bank-issued money — stablecoins are held 1-1 with reserve assets such as US Treasuries, making them a de facto arm of the US financial system.

What are the implications for a world in which digital dollars reach across economies fuelled by venture capital and tech innovation? And how does this challenge the thesis of diminishing dollar dominance? First, let’s understand how we got here.

The rise of the dollar

In the 19th century, the British Pound, bolstered by the reach of the British Empire, was the world’s number one currency. During the First World War, the global dominance of the Great British Pound, often known as Sterling, on international currency markets began to weaken. The United Kingdom and her Empire spent more than it could afford to on the war. The Second World War, just over two decades later, exacerbated the decline of sterling. Despite Britain “winning”, it was financially ruined, the trade empire collapsed and the US took the reins as the global hegemon. Since 1945 the US has been the world’s dominant power. And with global hard power (military) hegemony comes currency dominance.

As global powers rise and fall, currency wars happen. Sometimes explicitly and sometimes implicitly. Since 1945, not only has the US Dollar (cash) become the de facto global currency, but the main international card networks — Visa and Mastercard — are outgrowths of what started as US domestic payment systems. In the 1960s, there were only a handful of banks that issued Visa or Mastercard (all in the US), but today there are more than 10,000 issuers of Visa and Mastercard.

Even though Visa and Mastercard allow settlement in many currencies, a large share of transactions go via US Dollars. There are several reasons for this. Many countries clear through the dollar system rather than their domestic currency. Visa and Mastercard’s fees are often in Dollars, and many central banks don’t have the level of liquidity required to settle FX in their local currency.

The global payments system, as we know it, is dollar-centric. Stablecoins are the next frontier of dollar dominance. Everyone wants dollars. And, as it stands, stablecoins are often the best way to send, receive, and hold dollars. Crypto wallets, and increasingly neobanks such as Revolut are adding stablecoin functionality, thus allowing users to hold and transact in digital dollars. Added to this are the fintech startups backed by some of the leading venture capitalists in the world today.

As well as the dollar as we’ve long known it, startups everywhere are building for a world that interacts with, and uses, the digital dollar.

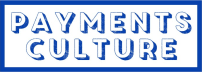

Some examples include DolarApp based in Mexico. The app can hold dollars (USD) or stablecoin dollars (USDC) — but to the user there’s no difference. The app logic decides which to use and when. Users only see a general dollar balance covering both assets, and USDC specifically is shown only when needed (for instance, when sending funds to another crypto wallet). Businesses can also set up accounts and send digital dollars 24/7 and near-instantly, whereas fiat dollars are stuck in the banking system paradigm of operating only in business hours.

Funding: In 2022, Dolar App raised a $5M seed round led by Y Combinator and Kaszek Ventures

Karsa is building a global bank based on dollar stablecoins with Pakistan set to be one of the first markets. The app features a USD account and a linked card, with the ability to earn interest on the account balance. Actually, Karsa’s website says interest in one section, and yield in another. Yield is the correct term. With crypto-based accounts, including stablecoins, yield refers to funds earning passive income in the crypto markets — and is not guaranteed. Hence, yield is sometimes provided as a range or based on current expectations rather than a set figure, as in traditional bank accounts or term deposits.

Funding: Karsa was part of Y Combinator, a startup accelerator, but has not raised a large funding round so far.

ZAR is aiming to build a global dollar wallet. Like with Karsa, Pakistan is ZAR’s first market. Although given their funding, the goal is to expand into additional markets sooner rather than later.

USDC is the stablecoin powering the app, and while the company mentions “your dollars, wherever you live”, they have also clearly catered to local nuances, and importantly, local compliance! The homepage mentions that, due to currency controls, some countries do not allow funds to be sent abroad. Addressing market-specific challenges is the right approach, especially if startups want to stay on the right side of local regulators. However, the more local nuances are catered to, the less global appeal a stablecoin wallet may have, particularly as users can always opt for a full-fat crypto exchange.

As well as individual accounts, ZAR offers merchant payment acceptance for businesses and an ambassador programme to allow users to benefit from bringing in new merchants. Showing how a stablecoin startup can build payment infrastructure as well as a wallet experience.

Funding: ZAR is the best funded of the three companies mentioned here. The company has raised a total of $20m, including a recent $12.9m funding round led by Andreessen Horowitz (a16z), with Dragonfly Capital, VanEck Ventures, and Coinbase Ventures also investing.

The downside of digital dollars

Startups —such as those noted above — exist due to genuine consumer demand in non-Western economies for access to dollars. Yet for the world outside the US, dollar stablecoins are not risk-free. They benefit those in countries whose currencies are unstable, and who would prefer to get dollars, but for Hélène Rey, Lord Raj Bagri Professor of Economics at London Business School, there’s another side which should be considered:

For the rest of the world, including Europe, wide adoption of US dollar stablecoins for payment purposes would be equivalent to the privatization of seigniorage by global actors. Along with easier flows linked to tax evasion, fiscal accounts could be affected. On the asset side, the backing of stablecoins means that increased international adoption of those pegged to the dollar could lower demand for non–US government bonds and raise demand for US Treasuries.

As the creation of money, at least in part, moves from governments and central banks to privately run stablecoin issuers, those issuers benefit from the profit of creating currency. But it seems inevitable that the line between fiat and crypto dollars will lessen. The line between sovereign and private money will, in some cases, dissolve, at least as far as the user is concerned.

The CEO of Tether, Paolo Ardoino, whose company issues the world’s largest stablecoin, with more than $183bn in circulation at the time of writing, is explicit about the reality of digital dollars. Last year, in an interview with the Guardian, he made clear his perspective:

We have 400 million users in emerging markets. We are basically selling the US debt outside the US … We are decentralizing the US debt as well, basically pushing for dollar hegemony. That’s how the US can maintain its dominance when it comes to its currency.

Yet as digital dollars grow in prominence, there’s an increasing risk that nations lose control of monetary policy. The more an economy becomes de facto dollarised, the less impact interest rate policy has. It takes a long time to reach that point, but it could be the end result for some nations in the years ahead. Ecuador gave up its domestic currency back in 2000, which has meant no independent interest rate policy, and no ability to strengthen or devalue the currency — even when local conditions call for it. The rise in digital dollars could make this shift happen organically, without a country formally choosing it.

How will policy makers respond? That’s another story. Sometimes it feels like tech and venture funding is running ahead of government and regulators. Why is this the case? Put simply. Everyone wants dollars.

Further reading:

Stablecoin growth – policy challenges and approaches (BIS Bulletin No. 108)

Top of Mind — Stablecoin Summer (Goldman Sachs Research)

Why the world should worry about Stablecoins (Martin Wolf in the Financial Times)

Thanks for reading Payments Culture. I appreciate it!

Please leave a comment or share with a friend or colleague if you enjoyed reading this edition. It’s much appreciated and helps grow the audience of this newsletter.

Note that views expressed on this Substack are my own and do not represent any other organisation. Also nothing I say should be taken as investment advice