How Geopolitics Shapes Fintech in 2026

Fintech is getting messier

Welcome to Payments Culture!

This newsletter explores how money moves, around the world — and why it matters.

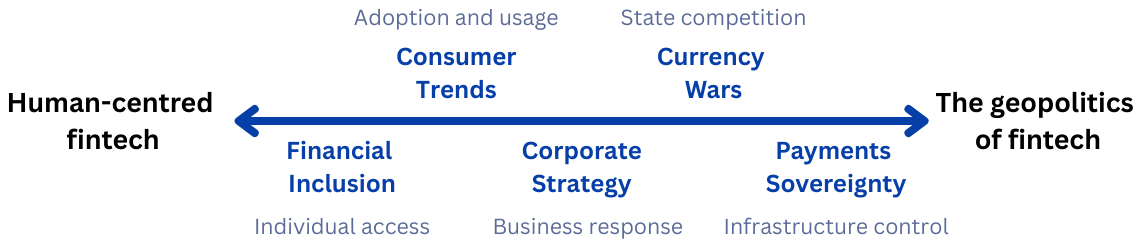

Originally, this was going to be an essay on the key fintech trends worth watching in 2026, and my predictions for where the industry is heading. You can probably guess some of the topics: stablecoins, agentic commerce, mobile wallets, and so on. Nothing too unique or remarkable. Likely 90% of the other 2026 prediction posts you’ve read would be similar. But don’t stop reading — at least not yet, because when I started to think a bit more deeply, I started to notice something else.

In this edition: why almost every trend in payments is impacted by our fracturing world, geopolitical competition is seeping through every layer of what we once thought were apolitical networks and rails. In short, fintech is getting messier.

Last week in Davos, Mark Carney, the Prime Minister of Canada, gave a speech that was lauded by many analysts for stating the reality of the world in 2026.

Every day we are reminded that we live in an era of great power rivalry… Many countries are drawing the same conclusions. They must develop greater strategic autonomy: in energy, food, critical minerals, in finance, and supply chains.

This analysis is spot on.

We can all see that the world is mired in tariffs, sanctions, wars, uncertainty. There’s no sign that these trends will decelerate. If anything, we are in a new normal. The world that we had from 1991 to 20221 has gone. The era of relative world peace that lasted from the end of the Cold War to the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine2 is over.

The changing dynamics

Today’s flux is partly because the unipolar moment is over.

For the past thirty years or so the US was the only superpower in town. In recent years the relative strength of other countries and blocs has increased. US domestic politics is changing the foreign policy discussion, with the US now focusing increasingly on the Western hemisphere (as seen in November 2025’s National Security Strategy document). Europe is beginning to stand on its own two feet, and Chinese influence is spreading globally.

To understand what all this means for fintech, we need to talk about geopolitics.

It’s a word we hear more and more in the news. Sometimes overused. But understanding how states and organisations interact through the convergence of power, resources, geography and technology is a useful lens for analysing how interconnected systems create both opportunity and vulnerability.

Fintech doesn’t exist in a vacuum — although sometimes industry commentary makes it sound as if it does. We often focus — and we can all be guilty of this — on the latest big trends, gigantic funding rounds, and outsized personalities while some of the biggest shifts, which really make the difference in fintech, are often missed.

How money moves is ever-changing, yet exactly how you’re impacted depends on your geography. In part, this is because geopolitics and fintech rub shoulders every day. You’ll find this dynamic in news stories nestled in the New York Times, The Economist, the Financial Times and beyond.

Consider a few examples from the past decade or so:

A post-Maduro bounce for e-commerce in Latin America?

Mercado Libre is Latin America’s answer to a super app. Almost 30 cents of every dollar spent online in the region is via the platform. In terms of fintech, Mercado Pago is its fintech arm, processing more than $142bn in payment volume in 2024.

Following the intervention of the US military in Venezuela and the ousting of President Maduro, Mercado Libre’s share price increased substantially. Climbing by 10% in the three days that followed the military operation.

In fact, stock markets across the region, including Venezuela’s, popped in the days that followed the raid. After over a decade of less-than-favourable economic policies (from the perspective of capitalism and free enterprise), investors are hoping that the Venezuelan economy will finally stabilise. Firms such as Mercado Libre may soon reap the rewards.

Visa and Mastercard’s exit from Russia

Following Russia’s annexation of Crimea in March 2014, as a result of US sanctions, Visa and Mastercard cut off several Russian banks from their payment networks, including Bank Rossiya, which US and EU officials claimed was the bank for Putin’s inner circle.

In response, Russia created the National Payment Card System (NSPK) to ensure all transactions stayed within local data centres. Additionally, a domestic payment scheme called Mir was established to insulate the Russian economy from further impacts of sanctions.

In the years that followed, several countries began to accept Mir cards. These were countries that are neutral or even friendly with Russia. For instance, Turkey, Belarus, Tajikistan, and Abkhazia — an occupied area of Georgia that’s under Russian control. (Cuba announced acceptance of Mir cards a bit later, in 2023.)

In 2022, following the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, Visa and Mastercard withdrew entirely from Russia. The country made up around 4% of each company's revenue in 2021. PayPal and American Express also exited Russia at the same time.

In the past few years many countries have stopped accepting Mir cards at ATMs and blocked them for payment acceptance. Turkey is one such example, and countries that still accept Mir cards often severely limit their acceptance due to the fear of secondary sanctions from the US.

India bans Chinese e-commerce apps

In 2020, following clashes in the disputed Ladakh region, India banned tens of Chinese-owned apps from operating in the country. The reason given was that the apps were prejudicial to the sovereignty and integrity of India, the defence of India, and the security of state and public order.

Alipay, Shein, TikTok and various e-commerce apps were among those banned.

This left space for domestic players to flourish — including UPI3 payment apps such as PhonePe and Paytm, as well as local e-commerce companies such as Myntra.

India's digital payments ecosystem, now insulated from Chinese tech, has become one of the world's largest.

There are plenty of other such examples. Almost every country is increasingly thinking of fintech and payments in terms of national interest. Regulation is increasingly shaped by geopolitical concerns. Market stability and consumer protection will always be important to regulators, but policymakers are acutely aware that financial flows can be impacted by events happening in faraway lands.

Case in point. A recent Bank of England paper found that “heightened geopolitical risk is negatively associated with a number of measures of bank stability such as non-performing loans and return on assets”. If central banks are paying attention, so should we. The schisms in trade, diplomacy, and trust can impact even our digital payment rails. What follows is an exploration of two areas where geopolitics and fintech come together: chokepoints, and resilience.

Note: It's worth making clear that geopolitics is not about picking a side, or expressing political views. Geopolitics is about reality, not polemics. It's about seeing the world as it really is, not as you would like it to be. This means understanding why states and organisations act the way they do, even when those actions may be personally objectionable. Geopolitical analysis seeks to understand, not to judge.

Chokepoints

Fintech arose through innovation and disrupting legacy tech. We’re at a stage where data can move, in a flash, across borders and systems. But the legacy rails remain, and the control of networks is a form of power. Scholars Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman explain:

Global economic networks have become a key terrain of geopolitical competition.

States that control central nodes in these networks can exploit asymmetries of interdependence to coerce other states.

For many decades the US has been the most substantial and consequential node in financial infrastructure. If you want to move dollars from one part of the world to another, even if it’s from Latin America to Asia, the transfer will likely go via US correspondent banks.

Author and former diplomat Edward Fishman explains in the video below that the dollar itself is the most important chokepoint, and pre-eminent currency across all use cases of money throughout the global economy. As a unit of account, as a store of value, and as a means of exchange4 — the dollar reigns supreme. Most banks, wherever they are in the world, primarily hold two currencies: their domestic currency and US dollars.

At an institutional level, central banks keep around 60% of their currency reserves in dollars, with the euro in second place at around 20%, and China’s RMB at 5% or below. Dollar dominance has meant the US has been able to wage economic warfare in a way that no other country can. Examples of countries hardest hit by economic sanctions include Cuba, Iraq under Saddam, Iran, and North Korea.

Yet working outside of the US dollar system is hard. But not impossible.

While there's often discussion of how transactions on blockchains can be tracked, enforcement is another matter. Without US-controlled chokepoints, sanctioned states have found ways to move value and garner digital dollars. Analytics firm Elliptic recently identified that Iran has acquired at least half a billion dollars of stablecoins, and this may be the tip of the iceberg — Iranian crypto exchange Nobitex allows users to store USDT. OFAC5, the US government agency that administers sanctions, isn’t going to go after ordinary Iranians, but those who deal with sanctioned exchanges outside the country will find themselves at risk of enforcement. Another heavily sanctioned state, North Korea, reportedly hacked $1.3bn in cryptocurrency in 2025, which passed through the USDT stablecoin on the Tron blockchain.

The irony is that countries barred from dealing in dollars in the real world have found ways to send and receive dollars on-chain. The goal is to keep it clandestine, but the activity is often visible. The chokepoints may be slowly losing their grip.6

Beyond evasion, other structural changes are taking place. The development of Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) is one force that could gradually erode dollar dominance. If countries can trade directly with each other electronically, the need for correspondent banks to facilitate trade in dollars will diminish over time. This is something that Ross Buckley has explored at length.

Resilience

As the global order discombobulates, we face additional risk. If chokepoints create vulnerability, then the response is to build resilience. This isn't only about dollar dominance, because in reality, every system has its chokepoints.7

The question to ask: what if the infrastructure we take for granted suddenly goes kaput? Some countries8 and companies are ahead of the curve, planning for worst-case scenarios, while others are gradually waking up and finally prioritising resilience.

In October last year, American banking giant JPMorganChase announced a $1.5trn Security and Resiliency Initiative. As part of the initiative, the bank will invest up to $10bn in select American companies. It comes with an impressive external advisory board including Jeff Bezos, Condoleezza Rice, and Michael Dell. Complementing this is the firm’s Center for Geopolitics, set up to provide clients with insights into the latest global trends.

While the scale of JPMorganChase’s activities stand out, geopolitical analysts such as Velina Tchakarova mention consulting with asset managers and other organisations to help business leaders manage through uncertain times. In 2026 we can expect executives to lean more on independent geopolitics experts for guidance.

Meanwhile, in Europe, the European Central Bank’s (ECB) chief economist Philip Lane believes that Europe’s reliance on American payment companies leaves it open to economic coercion:

We are witnessing a global shift towards a more multipolar monetary system, with payments systems and currencies increasingly wielded as instruments of geopolitical influence.

Such sentiments would have seemed far-fetched a decade ago. Although today, after many decades of reliance on the US, Europe is finally on a path to self-reliance in the military domain. Many want payments to follow the same path. At an institutional level the ECB is pursuing its own digital currency, but this is not scheduled to go live until 2029. In some markets, Wero — an account-to-account payment system that sees strengthening European sovereignty as one of its key objectives — is growing in popularity.

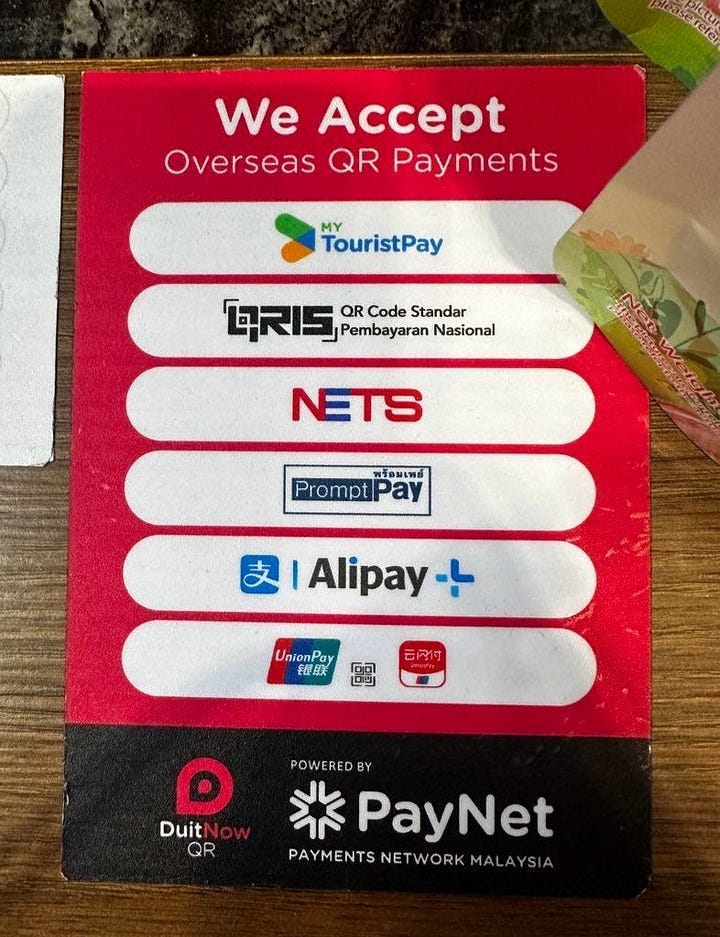

Asia is far down this path. Central banks and national payment authorities in countries such as Malaysia, Thailand, and India have developed payment systems that bypass card networks. Paying via a QR code, whether from a banking app or from within a super-app such as Indonesia’s Gojek, has become the norm across much of the region.

But a successful domestic payment system in itself isn’t enough — the next important step is interoperability. One of my key trends to watch in 2026: Asia’s interlocking mobile wallets. Asia is the most advanced region when it comes to building connectivity across domestic national payment systems. Chinese travellers can pay with their domestic payment apps, such as Alipay, when travelling in Thailand. Indonesia’s central bank is implementing cross-border payments for the QRIS scheme in China and South Korea. Even Hong Kong’s Octopus mobile wallet can be used in Japan via the popular PayPay system.

End note

Fintech is often synonymous with innovation.

Whether you’re accepting payments while running a shop in a favela in Rio or taking an Uber in Bangkok, such innovations have made our lives easier. But resilience and sovereignty are growing in importance too. Companies and countries want to ensure that whatever happens, their payment rails stay connected. Those who succeed will continue innovating while understanding that the ground is always shifting beneath their feet. This is a complex topic with many strands to unpick. Think of this essay as an introduction to how geopolitics is making fintech messier. Welcome to 2026.

Thanks for reading Payments Culture!

The meshing together of money, tech and geopolitics is one of my favourite topics so I really enjoyed writing this one. If you made it this far I assume you found it interesting too! 👾

Please leave a comment or share with a friend or colleague if you enjoyed reading this edition. It’s much appreciated and helps grow the audience of this newsletter.

Note that views expressed on this Substack are my own and do not represent any other organisation. Also nothing I say should be taken as investment advice.

Others would say the rupture was in 2014 with Russia’s annexation of Crimea, or some would even use the 2003 invasion of Iraq, but the broad consensus aligns with 2022 as the moment in which we entered this new paradigm.

Повномасштабне вторгнення Росії в Україну.

UPI stands for Unified Payments Interface and it’s India’s account-to-account payment system. In 2025, UPI processed over 228 billion transactions — and now handles more daily volume than Visa globally. Many of India's popular fintech apps are wrappers, offering extra services on top of UPI payments.

When two countries or organisations trade, the default currency they opt for is the dollar.

OFAC is the Office of Foreign Assets Control.

The US has successfully prosecuted various crypto CEOs including CZ of Binance, and of course Sam Bankman-Fried of FTX, but on a nation state level enforcing sanctions is seemingly harder for onchain traffic than in the traditional banking system.

In China, it was reported that some users lost access to WeChat — including WeChat Pay — after taking part in sensitive protests back in 2022. The app is so ubiquitous in China that some said losing access was akin to a digital death. Without WeChat Pay it could be almost impossible to pay at some venues.

Fearing a potential Russian cyberattack, or even an invasion, Latvia has equipped some ATMs with generators and built a system that allows card payments to operate even without connectivity.

Fascinating! And thanks so much for sharing my conversation with Eddie!

Amazing piece

I believe fintech is in very close proximity to geopolitics, and as more it continues to disrupt legacy financial services as more it will be closer and closer to geopolitics

Especially bearing in mind the data side of the equation, countries which are more embedded into financial systems of other countries with apps and services, will have more comprehensive picture for intelligence, surveillance and overall leverage over them