Did Curve Force Visa and Mastercard to Innovate?

Understanding Curve’s business model, how Visa and Mastercard reacted, and the innovation that followed.

Welcome to Payments Culture!

This newsletter explores how money moves, around the world, and why it matters.

Curve has been on quite a journey. It was founded by Shachar Bialick in 2015, and last week, after much speculation, Lloyds Banking Group1 announced the acquisition of Curve. The price is reported to be £120m (approximately US $165m). But the impact of Curve goes well beyond the relatively modest acquisition price.2

The fintech had grand ambitions from the get-go — to be the access point to “everything money” — yet in an early meeting the challenge was made clear. In that meeting, Mastercard reportedly laughed Shachar Bialick “out of the room.”3 Based on Mastercard’s rulebook, what Curve wanted to do wasn’t feasible. It wasn’t compliant. But like all successful startups, Curve’s vision shone through, they got up and running, and the rest is history.

If we are successful in our mission with Curve, you will still have Revolut, Amex, Monzo, and all those great fintech and financial institutions out there. It’s just that with Curve, we’re going to be this access point to your gateway to everything money. It’s going to be one place from which you access everything, exactly like with Spotify [and music].

Curve Founder, Shachar Bialick, talking on the Secret Leaders podcast earlier this year.

Curve has been one of the most interesting fintech startups of the past decade. The company’s impact has been broader than the UK market alone. What Curve built has had a global impact, and to understand the full picture a number of key questions need answering.

What did Curve build, and how did it work?

Was Curve’s approach a threat to Visa and Mastercard?

What is unique about the card schemes’ business models?

How did Visa and Mastercard innovate in response to Curve?

As a follow up, in a future edition of this newsletter, I’ll ask the question: Why did Lloyds Banking Group buy Curve? The answer will build on some of the key themes and discussion points from this essay, with additional insights on bank-level strategy.

Why Subscribe to Payments Culture?

Every week (or so), get one long-form email with my curated insights.

Some weeks, I’ll add additional content including personal essays, case studies, and interviews with fintech leaders.

Paid subscribers get at least 1x additional essay(s) per month, access to the full archive, and more features currently under development.

The long-form analysis found in this newsletter is not sponsored. I rely on readers for their support to keep writing. My next essay — out in the coming week — will be for paid members only. If you are able to support my writing it’s much appreciated.

Note: You can refer others via this link to earn complimentary a month of paid membership.

Understanding Curve’s Business Model

Curve’s business model is simple: users can combine all their credit and debit cards into a single card and one interface.

Users download the Curve app and add their existing non-Curve cards to their Curve account. Each time a card is added, users authenticate through their respective banking or credit card app. Prior to any payment transaction, users select their preferred card in their Curve app, which acts as the pass-through card for any subsequent transactions until the pass-through card is changed in-app.

Curve isn’t linked to a bank account or a direct funding source, but to the various cards added in the Curve app. When you pay with your Curve card, Curve fronts the transaction and pushes it through to the underlying card you’ve selected as the funding source.

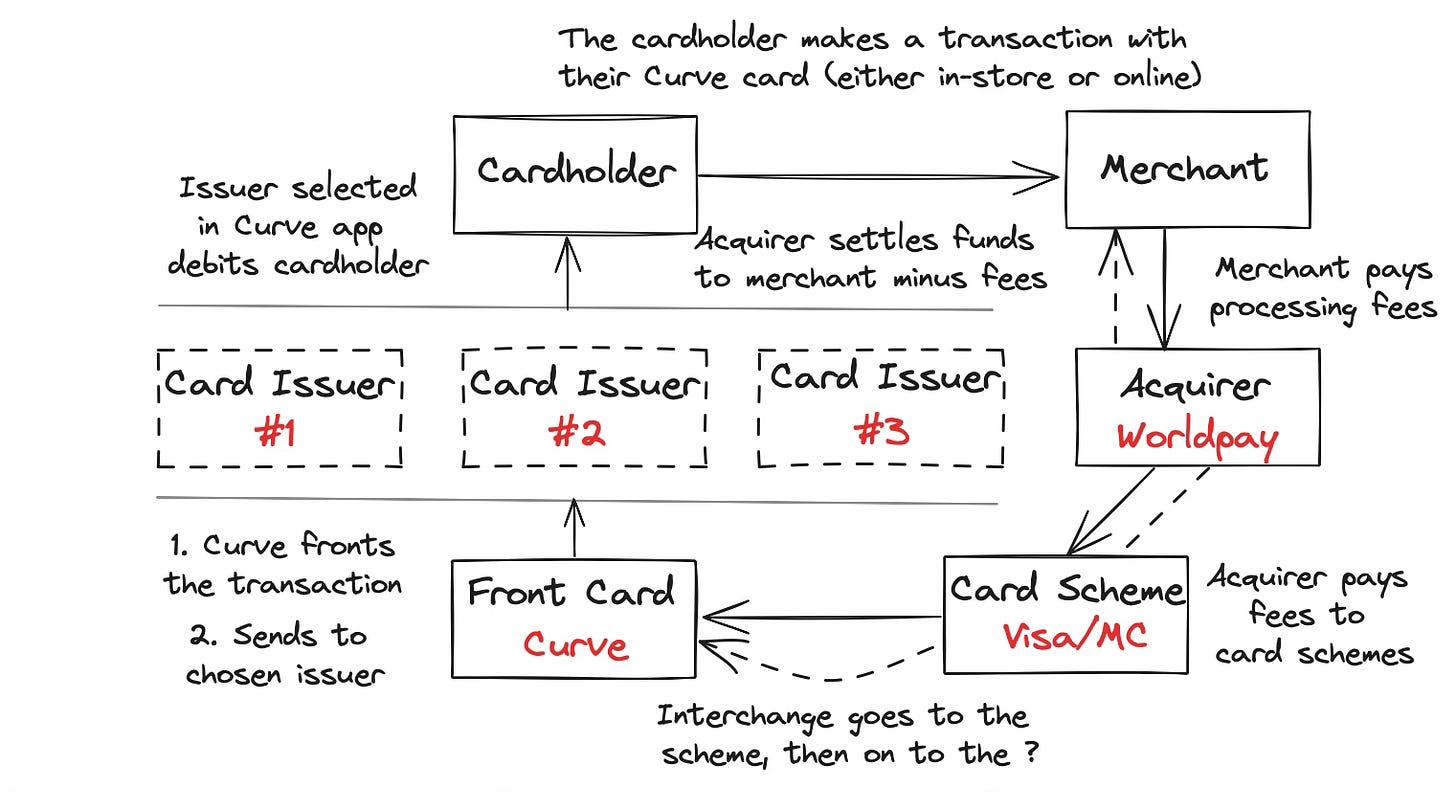

Consider how this model impacts a standard card payment transaction flow.

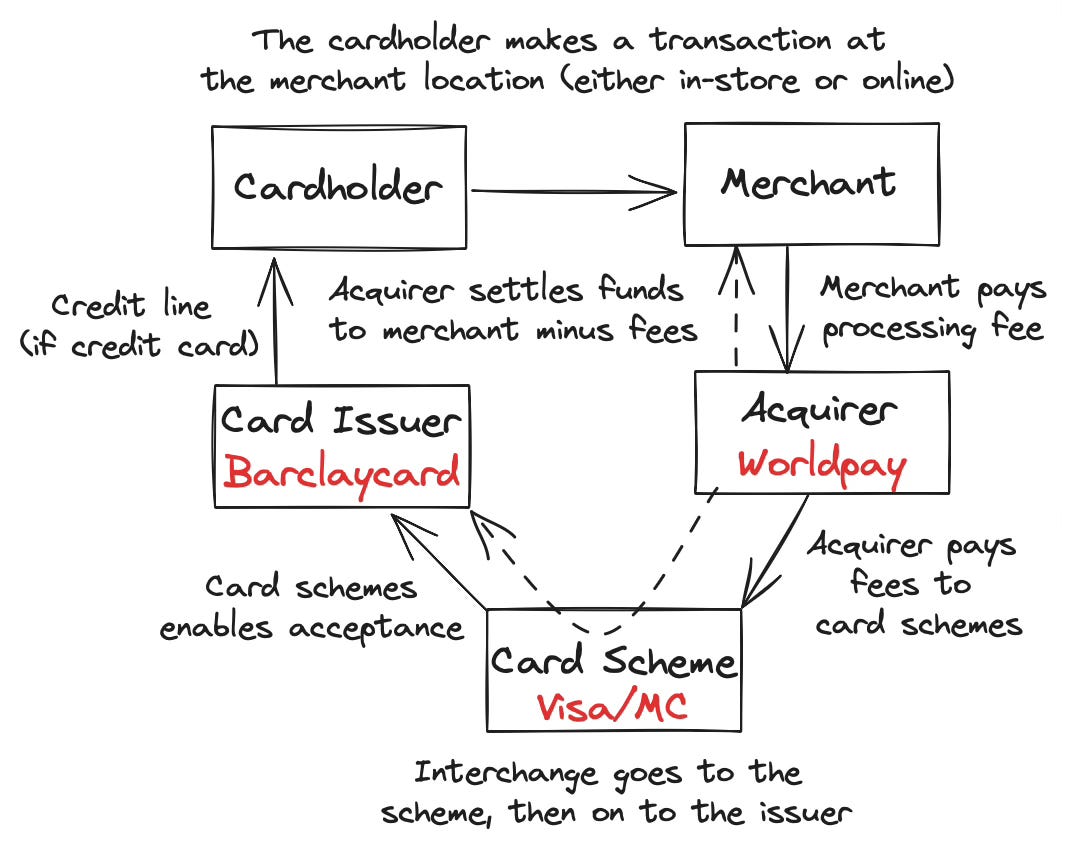

A transaction originates when a cardholder pays a merchant. What follows is the settlement of interchange and scheme fees to the card scheme4, and the cardholder gets debited for the transaction, with the merchant receiving funds net of any fees.

With a Curve transaction, the transaction flow differs.

From a cardholder perspective, it seems like there’s an additional step where the Curve card sends the transaction to the underlying card issuer.

However, the above diagram is actually wrong ❌

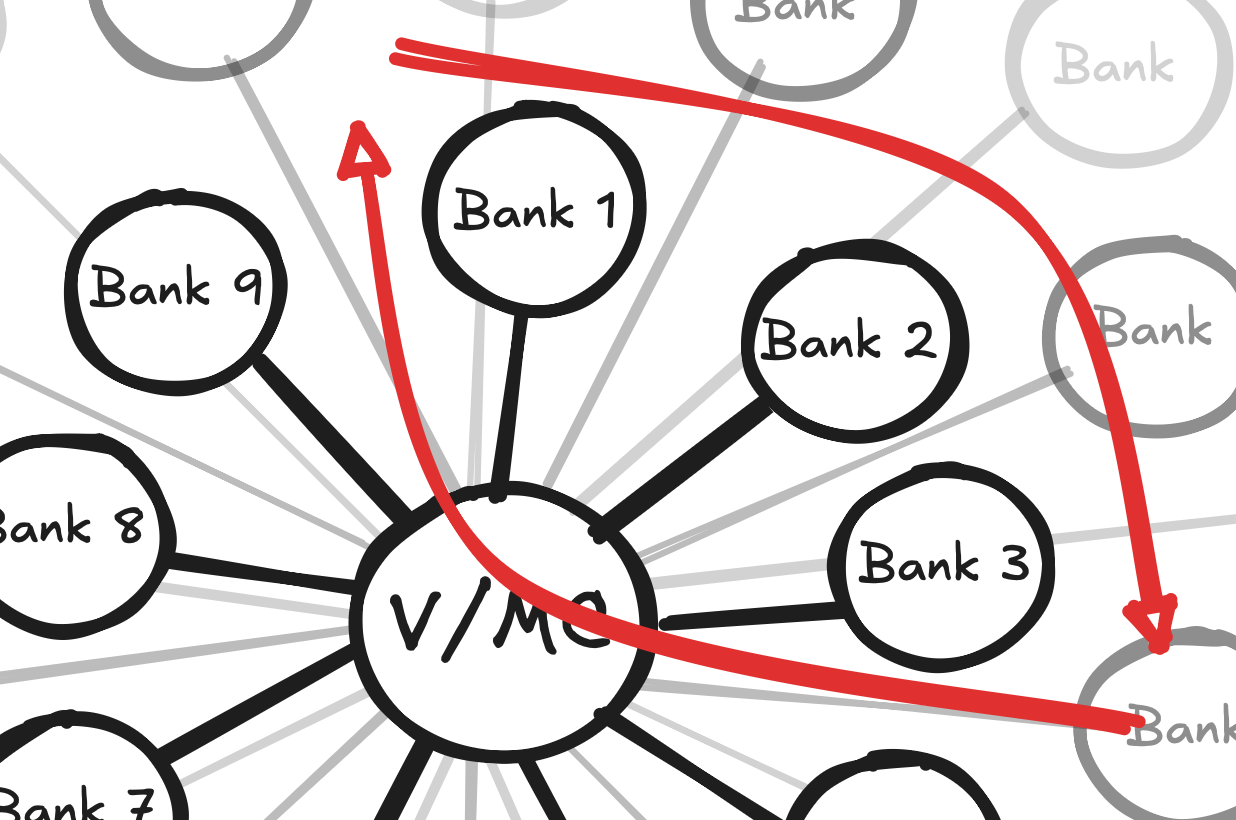

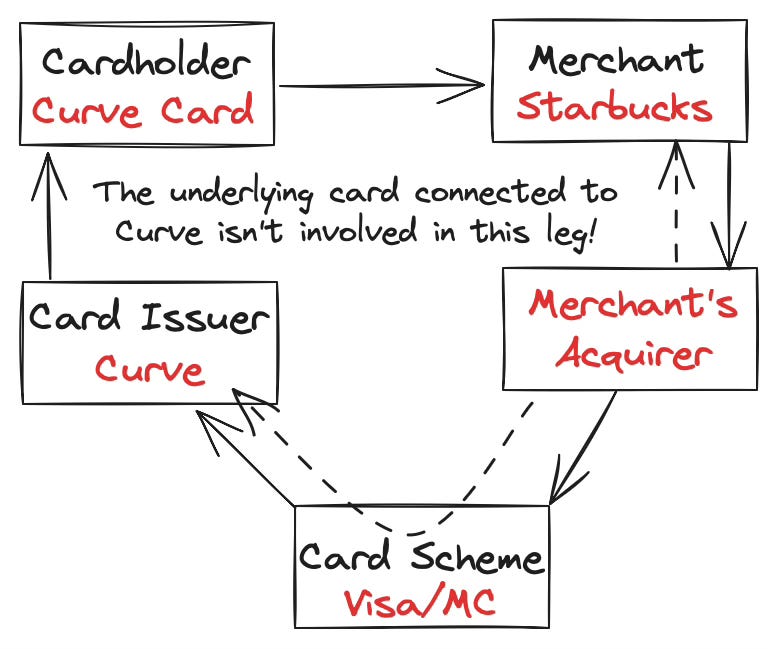

What’s taking place are two unique transactions. From a cardholder perspective it seems like a single transaction, but there are two legs. In order for Curve’s pass-through model to operate, two unique transactions take place almost instantaneously.

Leg 1 is what’s known as a Customer Initiated Transaction (CIT).

A CIT seems like a normal transaction initiated either in-store or online

But in this leg Curve fronts the transaction

This transaction is subject to Secure Customer Authentication (SCA) rules5

The merchant’s acquirer processes the transaction

And Curve — or their issuing partner — is the card issuer

The Curve app will show the full merchant name

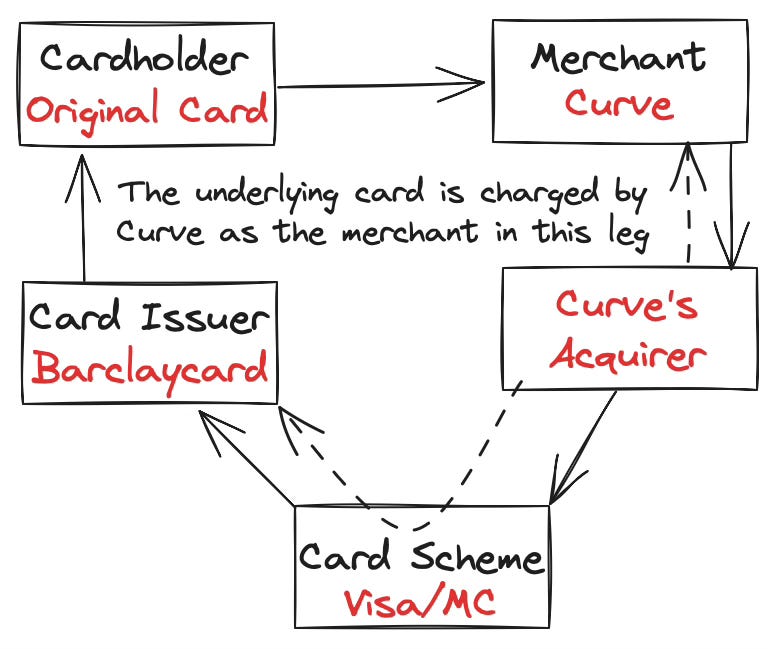

Leg 2 is what’s known as a Merchant Initiated Transaction (MIT).

The cardholder doesn’t see the MIT taking place

In this leg, Curve is the Merchant of Record (MoR)

This transaction doesn’t need cardholder authorisation, as the cardholder provided their permission to Curve to initiate such transactions when they added their card(s) to the app6

Curve’s acquirer processes the transaction

The issuer is the underlying card company or bank selected in the Curve app

The cardholder statement will show something like CRV*STARBUCKS

For card issuers, the downside of Curve’s model is that when Curve is used, they don’t get the level of information they expect, and are used to getting from each transaction. They know it’s a Curve transaction, but they don’t get merchant location detail, and even the full merchant name may not flow through. This lack of merchant-level information makes it hard for banks to detect fraud patterns and build customer profiles. On the other hand, Curve knows where you shop and how much you spend across the various cards connected to their app.

From a revenue perspective, Curve gains interchange revenue on Leg 1. In the UK and EU, this is 0.20% on debit card and 0.30% on credit card transactions.7 However, on Leg 2, Curve loses money. They have to pay the full set of acquiring fees as well as other related fees, such as any payment gateway costs. Additionally, if Leg 2 fails, Curve may retry the transaction, but if ultimately the transaction is unsuccessful, then Curve may bear a loss equal to the full transaction amount.

These factors mean that, structurally speaking, on a transaction-by-transaction basis, Curve’s business model is loss-making.8 The transaction economics mean that even if revenue per user rises through increasing interchange income, it won’t close the gap between top-line growth and profitability. To combat this, Curve expanded into adjacent areas and launched additional product lines away from this discrepancy between interchange income (Leg 1) and total fees (Leg 2).

Curve’s Other Revenue Drivers

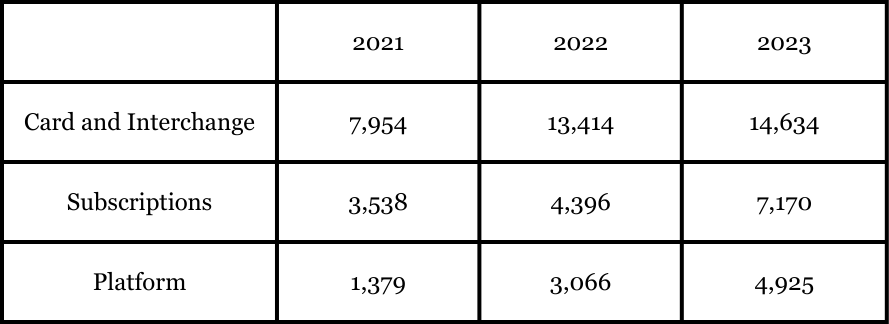

In the last available financial results9 — which are for the full year 2023 — after interchange income (£14.6m), Curve’s biggest revenue line was subscription income (£7.2m), and then platform income (£4.9m).

Platform income came from several sources. Retailers paid fees to be featured as cashback partners in the Curve app. Companies such as Samsung and Huawei used Curve’s technology as the mobile payments layer on some of their devices. And the platform income line also included FX fees, ATM fees, and revenue from Curve Flex — an instalment payment product.

Moving on to subscription income. This has become a mainstay of the fintech business model. Monzo, Revolut, and now even Klarna offer paid subscription plans. The consumer pays a monthly fee for a membership tier that offers benefits such as travel insurance, airport lounge access, and various company-specific benefits. In theory, the package that comes with any monthly membership should be good value for consumers yet profitable for the fintech.

Most importantly, the consumers who are happy to pay a monthly fee are likely to be the most engaged customers and use the product more than free users.10 Although for Curve, the challenge is that given the mismatch between Legs 1 and 2, a more engaged customer could, in some cases, equate to a less profitable customer.

Curve has paid plans at £5.99, £9.99, and the most expensive paid plan comes in at £17.99 a month — the top plan offers features such as “Unlimited past payment transfers from one card to another for 120 days” and “£100,000 fee-free spending abroad”. Some of the monthly fees are steep, yet Curve generated almost 50% of their interchange income from subscription revenue.

On closer analysis, the subscriptions numbers are not so impressive. If we take the £7.2m subscription income and assume an average monthly subscription of £10, this equates to around 60,000 paying subscribers. Given this £7.2m is from data which ends in 2023 (per the last available annual report), even being generous in future revenue assumptions means that less than 1.5%11 of the reported 6m user base12 have paid accounts.

Monzo is an interesting counterpoint. It is a company that has a more engaged customer base than Curve. Even though one is a bank and one is an all-in-one card — it’s not a like-for-like comparison — still, with around 1m paid subscriptions across their user base of more than 12m, Monzo has a paid subscriber ratio of 8%.13 The quantum of the difference illustrates the extent to which Curve has struggled to convert its customer base to paid subscriptions, while Monzo has been hugely successful.

There have been other examples of where Curve struggled with user engagement. Back in 2019, information leaked revealing that of Curve’s 500,000 customers only 14% were Monthly Active Users (MAU). This gave credence to the view that some had long held about Curve. It was an app many users downloaded to test and try, but they rarely stuck with it. They didn’t see the benefit. This was especially the case in markets like the UK, where the popularity of Apple Pay meant that users already had a de facto mobile wallet that held all their cards.

Curve had to work hard to stay relevant, while consistently innovating and seeking to grow their user base, all while trying to close the gap between revenue and profitability. The company made cumulative losses of at least £140m before acquisition.14 However, they still undoubtedly had a substantial impact, and to understand this significance, we need to get into the skin of how the card scheme giants operate.

Curve vs Visa and Mastercard (and Amex)

Curve has developed a unique and innovative business model that relies on access to payment networks and is subject to their rules. Payment networks could adopt new operating rules, or reinterpret existing rules, which would hamper Curve’s business model.

Curve’s annual report for the financial year ending 31st December 202315 highlighted a key risk to the business model. If the payment networks changed their rules then Curve would struggle. Their innovative business model was dependent on the card network’s support.

Initially, Curve founder Shachar Bialick struggled to get up and running. He’d built a prototype with £1.2m of seed funding, but in order to launch, he needed one of the two main card networks — Visa or Mastercard — to approve his business idea.

Once one was onboard, he knew the solution could be used at every merchant location that accepted Visa or Mastercard. The opposite scenario, if he couldn’t win over one of the two card giants, would be signing up merchants and partners directly, something which would be time-consuming and resource-intensive. But with one of the large networks on board, he could short-circuit the acceptance side. However, achieving this was tough.

Mastercard were not initially supportive with Curve’s approach, but after much wrangling, they permitted a pilot of Curve in 2016 before a full public launch in 2018.

Mastercard reportedly laughed Shachar Bialick ‘out of the room.’ Based on Mastercard’s rulebook, what Curve wanted to do wasn’t feasible. It wasn’t compliant. But like all successful startups, Curve’s vision shone through, they got up and running, and the rest is history.

Mastercard were initially sceptical as Curve changed core aspects of the card payments model. For instance, the fact that the card presented for payment isn’t the ultimate funding source for a transaction was a big change. And some of Curve’s features, such as Go Back in Time16, allowed users to change the funding source up to 120 days after the initial transaction, was something that hadn’t been seen before. In many respects, Curve’s product offering sat in a compliance grey area — it was a solution that didn’t fit within existing business models, such as that of card issuing, processing, or programme manager.17

Although, it was always like that either Visa or Mastercard would agree to work with Curve. If the concept was a success, there was plenty of upside in terms of additional transaction revenue, especially since there would be two sets of scheme fees18 for every normal transaction. Additionally, while Curve did pose a challenge for the card schemes’ existing rulebooks, regulations such as PSD219 led to more open competition.20

Crucially, the regulation confirmed that Merchant Initiated Transactions (MIT) would not be subject to the same customer authentication rules as Customer Initiated Transactions (CIT). Therefore, Leg 2 in Curve’s business model could remain friction-free, provided the underlying card had been authorised by the cardholder when loading into the Curve app.

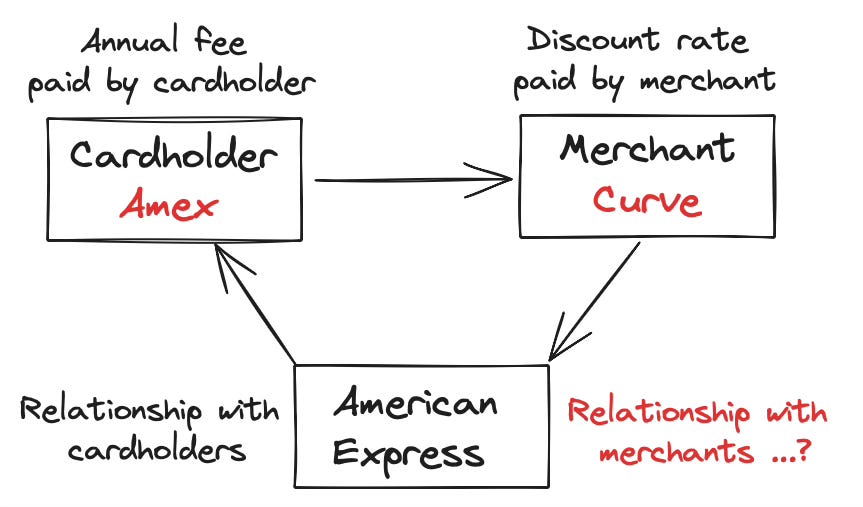

At this point it’s worth noting Curve’s travails with American Express (Amex).

Initially, one reason many UK consumers got excited about Curve was that it supported Amex cards. While the situation has gradually improved over time, fewer businesses accept Amex cards than Visa or Mastercard cards. This is due to cost. Amex nearly always has higher fees than Visa and Mastercard, which means some retailers refuse to accept Amex.21 Retailers can take this stance as every cardholder will always have at least one other card in their wallet (or Apple Wallet) that they can use if Amex is not offered as a payment option.

Consumers were happy that via Curve they’d now be able to use Amex everywhere. To retailers the card would appear as a Mastercard transaction (Leg 1). Leg 2 would operate differently for Amex than for other card brands, as Amex operates a closed-loop network in which it is both the card issuer and the acquirer.

As Curve’s UK volumes grew, Amex was frustrated by the lack of data and the general operating model of Curve. Amex has strict acceptance criteria and sees its offering as a premium brand. For Amex, they want to stay front and centre — and not just act as a funding source. Amex blocked Curve after a few months in 2016, and while they relaunched Amex support with a different model22 in 2019, this didn’t last long either.23

Competitive and Business Model Dynamics

Curve’s relationship with Visa and Mastercard has been one of coopetition. Curve needed the card schemes for reach, but the ultimate business model conflicted. To understand this conflict in more detail, we need to understand the differences in the respective business models. Curve sought to offer their users payment choice from one connection point. But the card schemes have a business model that is dependent on deep and enduring relationships with their issuing bank partners.

Coopetitive relationships are complex as they consist of two diametrically different logics of interaction. Actors involved in coopetition are involved in a relationship that on the one hand consists of hostility due to conflicting interests and on the other hand consists of friendliness due to common interests.

From a paper by Bengtsson and Kock, who popularised the concept of coopetition — a relationship in which firms cooperate and compete with each other at the same time.24

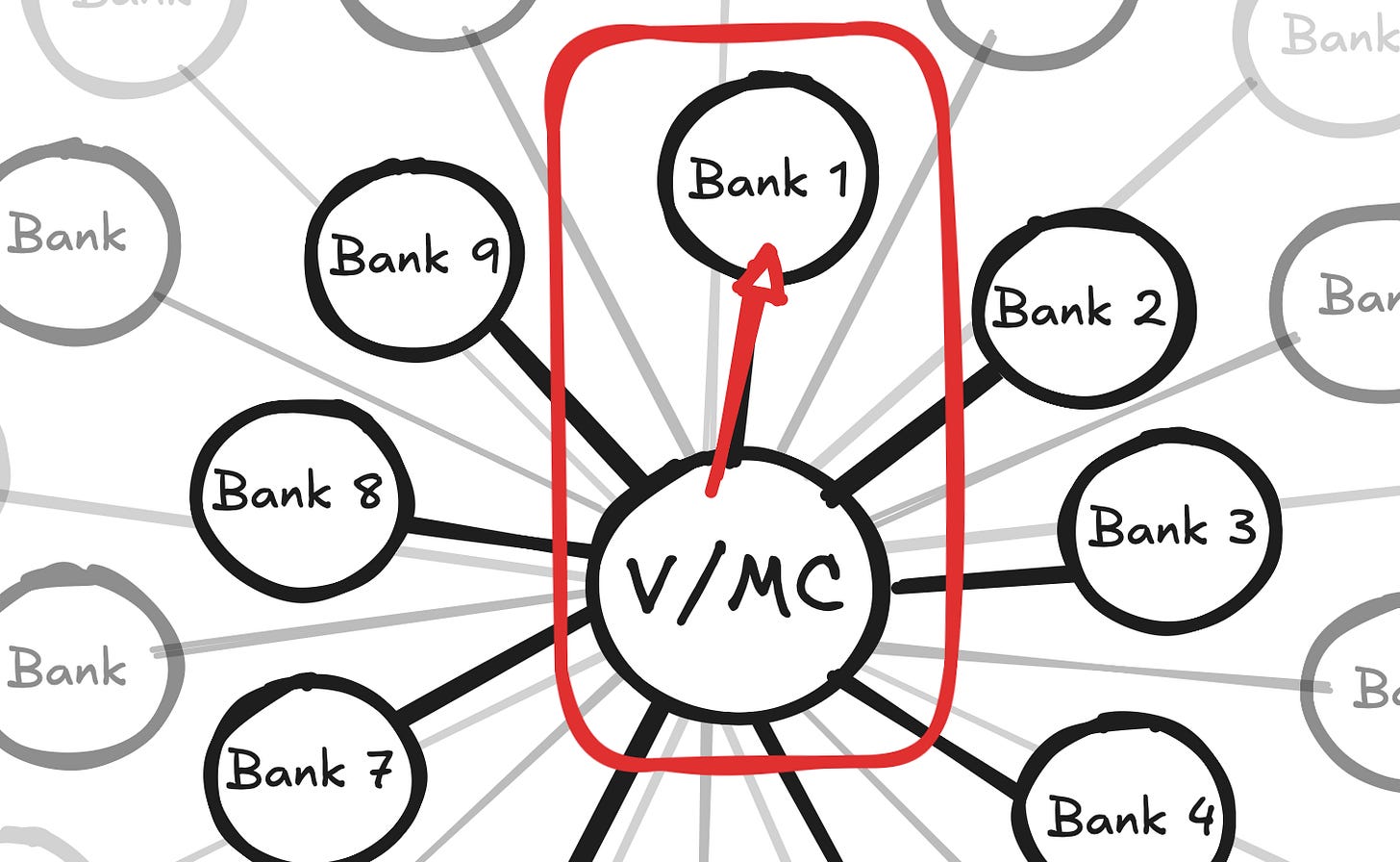

Visa and Mastercard’s core customers are, and always have been, issuing banks.25

Their networks facilitate card payments globally, and banks know their customers can spend in almost every country in the world, provided their cards have either a Visa or Mastercard badge. The companies have diversified into other products in recent years, including payment gateway solutions, fraud prevention, and more recently, stablecoin offerings. Yet the vast majority of card scheme revenue still comes from card issuing relationships.

In the 1960s, neither card scheme had more than tens of bank partners and all partner banks were located in the US. Today, there are thousands of financial institutions, located in 200+ countries and territories, that work with Visa and/or Mastercard.

Within Visa and Mastercard, every bank has an account manager. For large institutions, the relationship can be intensive—entire teams work with these major banks day-to-day to optimise card programmes, launch new products, and grow their business together. Some of the world’s largest issuers may have ten or more dedicated Visa or Mastercard staff involved day to day in their partnership. In return, these banks generate enormous revenue for the card schemes. As you would expect, the precise numbers behind any particular partnership aren’t disclosed, but with both networks earning a small fee on every transaction, there are many issuers generating tens of millions of pounds in card scheme fees annually.

So if we consider that Visa and Mastercard both benefit from deep long-term relationships with their issuing bank partners, then Curve differs. Its business model isn’t concerned with depth of issuing bank relationships. Rather, the ability to switch between issuing banks is the central aspect of Curve’s model.

Curve’s customers are its users — those who log into their app every day and choose which card to apply to which transaction. Issuing banks themselves are merely one of many connection points.

With a model like Curve, there’s always the potential to bypass issuing banks entirely for some transactions. This is something that Curve has tried with their cashback product. Known as “Curve Cash” which provides cashback of 1% (or more) at selected retailers. The cashback is returned to the user as stored value within the Curve app, and then shows as a “Curve Cash” payment option. It’s a quasi-currency that can be accumulated, selected, and then spent like any other payment option. This was a clear example of how transactions could take place without any bank involvement. And while users accumulated only modest amounts, the concept was proven. In the future, issuing banks would potentially be only one of the payment options for Curve account holders.

Curve needed the card schemes for reach, but the ultimate business model conflicted. Curve sought to offer their users payment choice from one connection point. But the card schemes have a business model that is dependent on deep and enduring relationships with their issuing bank partners.

As years went by, the two card schemes could see Curve’s growth. US expansion barely got out of first gear before pulling back, yet Curve had, for the most part, shown real momentum.26 Hype often followed the company, it innovated quickly in expanding its product offering, and while it never turned a profit, its numbers were improving over time. But it wasn’t enough. Curve got acquired by Lloyds Banking Group after expressing concern that the company would run out of money if it didn’t find a buyer this year.

The reality is that Curve was never a competitive threat for Visa and Mastercard. It needed them. They worked together. At the same time, Curve proved that its model of switching between cards worked — at least to some extent. In recent years, both Visa and Mastercard responded with their own offerings, which took inspiration from Curve. However, as you would expect, the models the card schemes settled on were different; their offerings are issuer-centric, in line with their overall business models.

The New World — Credentials Over Cards?

While Mastercard was Curve’s primary partner, periodic discussions with Visa were held to keep Visa informed of Curve’s business and explain the operating model. This dialogue was critical as Visa never blocked Curve. Visa kept a close eye on how the fintech operated, and it was Visa who first launched the card networks’ answer to Curve.

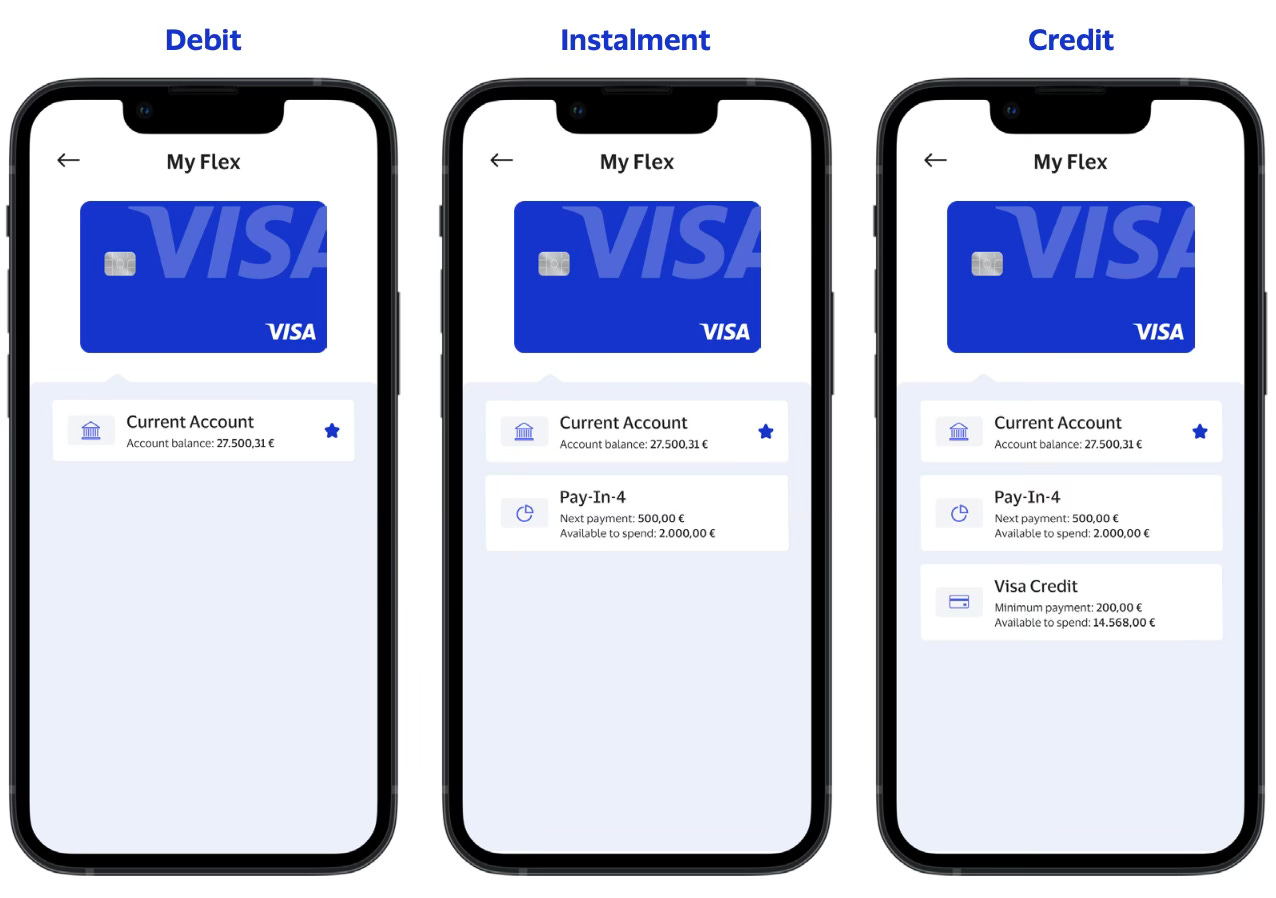

Visa Flexible Credential (VFC) was announced by Visa in 2024 and launched first in Asia before announcing partnerships in the US and the Middle East later in the year. The product assigns a specific card number to a VFC customer account.27 This is known as the primary credential, and once assigned, allows consumers to dynamically select from various funding sources — known as secondary credentials. Examples of funding sources include debit, credit, instalments, as well as joint accounts, multi-currency accounts, and rewards points.

The financial landscape is undergoing a radical transformation, and at the heart of this revolution is the move towards flexible payment credentials. Traditional one-size-fits-all credit is rapidly being replaced by dynamic, consumer-centric financing options

simon khalaf - Ex CEO of Marqeta, writing recently on his Substack

The innovation is a single payment credential with rules that route spend based on predefined criteria.28 Use cases include:

Users may utilise their debit card as their main day-to-day spending card.

But for transactions over £100, they can direct this payment to a credit card.

Transactions over £1,000 can be split into instalments, such as the option to pay in four equal instalments.

For some couples, even if they keep individual accounts, they may wish to pay their utility bills from a joint account and direct debit payments specifically to a joint account.

In some markets, consumers pay in both local currency and non-local currency — such as US Dollars. Rules can change the funding source between different currency balances.

Some card issuers offer rewards points as part of their ecosystem and users can draw on their rewards points at certain merchants.

The transaction is authorised on the primary credential and then settled to Visa with the secondary credential alongside information confirming it was a VFC transaction.

This difference between funding source and payment source is one similarity with Curve’s model. Yet in the case of Visa’s offering, the main difference is that the primary and secondary credentials are both within the same issuing bank. This should be no surprise. Visa’s core customers are issuing banks, and improving the offering of issuing banks and level of spend within banks is a core objective of Visa.

Mastercard launched a similar product to Visa Flexible Credential called Mastercard One Credential. The products position themselves slightly differently, yet for their bank partners the outcome is the same. Both provide a rules engine to select a transaction funding source on top of existing card rails, with APIs for issuers, and settlement that links primary and secondary credentials.29

What we’re not doing at this time is going beyond the walls of their bank and asking the consumer to connect other accounts from other institutions. Note that this is not a design limitation—it’s actually by design.

Mastercard’s Chief Consumer Product Officer Bunita Sawhney confirmed that Mastercard actively seeks to keep the user within the walls of their bank. This is a key aspect of the card schemes’ response to Curve — provide infrastructure to issuing partners to build their own flexible model within their own ecosystem, as reported in The Financial Brand.

We’ve seen that Visa and Mastercard’s response to Curve was to build solutions within their own ecosystems to help deepen relationships with their issuers. Essentially, if you can utilise multiple funding sources within one bank, then why would you want to utilise external funding sources? But ultimately it’s up to issuers themselves to make their proposition compelling for consumers.

One last point I want to make is how flexible credentials change the competitive dynamic between Visa and Mastercard. This is potentially the most unexplored aspect of this story.

In terms of card issuing, ways in which Visa and Mastercard can grow revenue include:

Capturing organic transaction growth from increasing volumes of card payments as more of the world economy goes cashless.

Raising charges from card scheme fees, which are not regulated to anywhere near the extent that interchange fees are.30

Winning volumes from each other!

The last point is key. Many banks traditionally maintain relationships with both Visa and Mastercard. It’s common for banks to use one network for debit cards and the other for credit cards. The account managers within Visa and Mastercard are looking to grow volumes with each issuer they manage. And banks know that by actively using both card schemes, they can compare and contrast service levels, product innovation, and commercial value offered by each network.

However, flexible credential products only function effectively if a bank’s entire portfolio is either with Visa or Mastercard.31 If your credit cards are with Visa but debit with Mastercard, then you can’t switch between them. This creates a “winner-takes-all” dynamic where success in selling a flexible credential approach also depends on converting as much of an issuer’s portfolio as possible to the respective network.

This dynamic is why you’re likely to see many neobanks and spin-off banks opt for flexible credential offerings in the short term, rather than longstanding traditional legacy banks. Newer organisations have a clean slate in terms of card scheme relationships and will find it easier to opt for one network wholesale. They also have API-first architecture suited to integrating with third-party providers, which is helpful, as flexible credential offerings will often require third parties to help integrate and run aspects of the programme.32 Additionally, while legacy banks often manage their credit and debit portfolios separately — sometimes even within different parts of the bank — neobanks don’t have this constraint.

Thanks for reading Payments Culture!

Please leave a comment or share with a friend or colleague if you enjoyed reading this edition. It’s much appreciated and helps grow the audience of this newsletter.

Note that views expressed on this Substack are my own and do not represent any other organisation. Also nothing I say should be taken as investment advice.

Lloyds Banking Group is one of the UK’s four largest banking groups, and is the parent company of Lloyds Bank, Halifax, Bank of Scotland, and credit card provider MBNA.

According to Banking Dive, the sale price of around £120m was less than half the £250m that Curve raised from investors, including many crowd funding investors.

Discussed with Curve’s CEO Shachar Bialik on the Secret Leaders podcast in early 2025.

The interchange fee gets collected by the card acquirer, settled to Visa or Mastercard and is then forwarded to the card issuer as their fee for enabling the transaction.

Secure Customer Authentication (SCA) is mandated in the UK and EU. It involves a two-step verification process for payments that meet certain criteria. Some examples include adding a card to Apple Pay or Curve, most online transactions, and in-person transactions over a certain value. In many cases transactions can avoid the two-step verification process if they meet certain risk-based criteria, or are white-listed by the cardholder.

A well-known examples of a Merchant Initiated Transaction (MIT) is Uber. In a process many of us will be familiar with, a cardholder authorises the transaction when booking the ride and when the ride is completed Uber initiates the payment.

The assumption is that in most cases Curve gets debit card revenue, however there may be cases where Curve higher interchange (credit rates) such as with Curve’s instalment product.

One factor which I haven’t mentioned but could be discussed in some detail is the fact that Curve offers both consumer and commercial cards, in the latter case these would primarily be used by small businesses. I’ve not come across information highlighting the split between consumer and commercial cards, but one key point is that commercial cards have higher interchange — they are not regulated in the UK and EU in the same way that consumer cards are. This means that the economics on commercial cards would differ somewhat compared to consumer card, however if the underlying funding source is the same card type then in theory the transaction economics would be largely similar.

The financial metrics are from the Curve Group OS data available on Companies House.

Many consumers are happy to pay a monthly fee for a fintech subscription. But there’s a limit to the number of subscriptions they will take out. Unless consumers feel they are getting good value for money they won’t continue to pay the monthly fee, and they’ll cancel their monthly subscription. Hence, to varying degree, fintech subscriptions are competing with each other as consumers will likely have only a small number of apps and cards they use regularly. Each subscription will need to justify itself based on its share of spending and value.

Taking £120 as the average subscriber income means that with £7.2m total subscription revenue the ratio of paid to free accounts is 1% of Curve’s 6 million user base. However I’m cautious that the 6 million user base is from 2025 whereas the revenue numbers are for the financial year and also full year 2023. Therefore even being generous in future, or non-disclosed assumptions, the ratio of paid to free accounts is no more than 1.5%.

The reported 6m customer number is total accounts on the platform — not active users. Also this number reflects all markets in which Curve operates.

Numbers taken from Monzo’s 2025 Annual Report which mentions more than 12 million customers and more than 1 million paid accounts.

This number is based on the cumulative losses reported in publicly available annual reports from 2018-2023.

Published on Companies House under the company name Curve UK Limited.

Go Back in Time allows Curve users to selected a transaction in the Curve app and change the funding source from one account to another even months after the initial passthrough transaction. The 120 days limit may be due to the potential to raise a chargeback on the original funding source if there is an error when changing funding source (usually 120 days is the maximum time limit to raise a chargeback with the card schemes).

A programme manager is a company that runs the business side of a debit or credit card. They are responsible for the operations, compliance, risk management and other aspects of a card programme, but usually do not manage consumer relationships directly, and often do not directly hold a banking license.

There are three fees associated with every card payment transaction: interchange; scheme fees; and acquirer margin. Scheme fees are usually the smallest of the three fees proportion of the transaction value. They go directly to Visa or Mastercard as to cover their costs and as their margin for facilitating the transaction.

The Payments Services Directive 2 (PSD2) is an EU-wide regulation that came into force in January 2018, but various aspects of the regulation were phased in over time. After leaving the EU, the UK transposed PSD2 into domestic law, where it continues to apply.

The momentum created by PSD2 and its predecessor PSD1 is discussed by Curve’s founder Shachar Bialik in this interview with Future Nexus. The idea is that the regulations were opening up new possibilities for fintech — by moving payments from a bank-led business model to more of an open ecosystem.

As I’ve noted in other posts, part of the dynamic here is that Amex cards are not regulated in the same way as Visa or Mastercard, at least not in the UK and EU. Amex’s fees are not capped, therefore as a consumer, an Amex card means better rewards — derived from higher fees that businesses pay— and with that sometimes comes a reluctance to accept Amex cards.

While not every detail is public, and therefore cannot be confirmed, it’s possible that the first time Amex was offered as funding source by Curve it was via a third-party acquiring arrangement, which would mean worse economics for Amex than a direct acquiring agreement. The second attempt was with a direct Amex merchant acquiring agreement but despite various discussions Amex never got comfortable with the model.

A full breakdown of the Amex-Curve relationship is outlined in this Head for Points post, which features Curve’s commentary on their engagement with Amex during that time.

Bengtsson, M., & Kock, S. (2000). “Coopetition” in business networks – to cooperate and compete simultaneously. Industrial Marketing Management, 29(5), 411–426.

I use the term issuing banks here as a catch all for companies that provide credit and debit cards to their customers. Usually this is banks, but it may be card issuers who are not actually banks, which from a regulatory perspective, can differ per country and across business models. But for the purpose of simplicity I’ll use the term issuing banks when describing Visa and Mastercard’s main clients.

In 2021 Curve raised a funding round with an explicit focus on US expansion. The company launched its beta programme in March 2022, but they put US plans on-hold in March 2025.

In industry terminology we can say that specific BIN ranges are assigned to Visa Flexible Credential. BIN ranges are the first 6-8 digits of a card number and reflect the issuing bank and also the product type — for instance different BIN ranges are assigned for credit and debit cards within the same bank.

Although it wasn’t part of the early product offering. Curve now also offers the ability to route to various funding sources based on predefined rules such as transaction size and merchant category. But as mentioned, with Curve this means the ability to go across issuers and not be limited to staying within one issuer’s product set.

As a brief aside, I put nearly all my spend onto one credit card and pay it off in full each month. Occasionally I change this card, but I never change my spending card based on various factors such as transaction amount. Perhaps many people do. The research I’ve read does not conclude this conclusively. Although perhaps when consumers are provided easy options to opt for various funding models in their banking app it may be something more consumers consider.

Some studies have shown that when the EU regulated interchange fees in 2018, in the following years card scheme fees rose significantly.

Of course it doesn’t have to be every single card programme, but the more cards that are kept with the other network(s) the less useful the flexible credential will be.

Such as Affirm for instalment payments or Marqeta for the core processing elements.

Nice breakdown and appreciate the long form analysis; all excellent. There are definitely some interesting sub-topics worth exploring like coopetition (e.g. when is it beneficial to the end user, issuer and network).

I want to offer some views:

1) I was working in Visa AP product and I remember discussing Curve with colleagues. I don't believe Visa ever supported Curve or a product like Curve - it was all in Mastercard's camp. It was seen as fronting the transaction and therefore against the spirit of the rules.

Because the unit economics, business model NEVER made sense (and it played out to be the case), we were dismissive of such products and put it into the bucket of it will fail soon enough.

2) Nium launched their Amaze card (also on MC) with this feature in Singapore. Like Curve, I believe the USP wasn't strong enough and they have since taken it off (I think).

3) Regarding Flex credentials, great point you have raised - does this even make sense for traditional bank issuers? I don't know if I would connect the origination of Flex credentials with what happened at Curve. At the end of the day, as you highlighted, there weren't many recurring users and the heavy users are likely the revolvers (yikes)...

This was a brilliant breakdown 👏