Eleven Ways That Apple Pay Changed Payments — Part 1

Core Impacts From Eleven Years of Apple Pay (2014-2025)

Welcome to Payments Culture!

This newsletter explores how money moves, around the world, and why it matters.

I’m currently looking for new opportunities. I’m open to short-term assignments as well as permanent positions. You can email me or contact me on LinkedIn to discuss further.

Apple Pay has been a huge success. The service launched in the US on October 20th 2014, and today, from Canada to Paraguay to Vietnam, thousands of banks support Apple Pay. The solution is available in around ninety countries so far, with more added every year.

Last year I wrote How Apple Pay Changed Payments. This was one of my most popular posts of the year and it was rated as one of the Best Deep Reads of 2024 by This Week in Fintech. But there was so much more I could have said. Over the next two posts I’m going to tell the story of Apple Pay through eleven changes that have impacted payments.

In this post, you’ll learn:

How Apple succeeded with mobile payments, where earlier attempts failed

How Apple Pay made fintech more accessible

How Apple Pay generates more revenue than many standalone companies

How transit payments became the ultimate testing ground for Apple Pay

How Apple Pay cemented the global divide between cards and QR codes

Let me be clear: many of the things I’m going to discuss may have happened, and may have progressed without Apple Pay. Yet my argument is that Apple Pay ignited a seismic shift. The launch of Apple Pay was one of the most impactful events in the industry. It made so many things possible in a way that we take for granted today.

#1.

Apple Pay Succeeded Where Other Mobile Payments Failed

In an interview with the Wall Street Journal last year, Tim Cook, when quizzed about Apple’s perceived slowness in rolling out AI, stated “We’re perfectly fine with not being first. As it turns out, it takes a while to get it really great. It takes a lot of iteration.”

Apple’s instinct is to be the best, not the first, and Apple Pay was no exception.

Two examples from before the Apple Pay era help set the scene. One success1 and one failure can help illustrate the challenges Apple would face.

The Success of FeliCa (from 2004)

Japan got its first NFC-enabled phones2 way back in 2004.

Sony and NTT Docomo, Japan’s largest mobile operator, formed a joint venture called FeliCa Networks. FeliCa developed a standard which soon became the dominant NFC system not just in Japan but across East Asia.3 Major retailers such as FamilyMart accepted payments via FeliCa, and by 2011, mobile payments accounted for around 12 percent of Japan’s cashless transactions. However, with the rise of the iPhone, the share of mobile payments declined, and it wasn’t until 2016, with the launch of Apple Pay in Japan, that Apple added support for the FeliCa standard.4

Google Wallet Struggles (from 2011)

The first Android phone with NFC was Google’s Nexus S, which was manufactured by Samsung and released in December 2010. Google launched mobile payments with a solution known as Google Wallet in 2011 with the updated Nexus S 4G. The initial launch was with one carrier (Sprint), one card issuer (Citibank), and relied on merchants having contactless payment terminals supplied by Mastercard.5 Google struggled to scale the solution.6 This should be no surprise given that in 2011 less than 0.5% of all payment terminals had contactless acceptance capabilities! The solution was stuck in a chicken-and-egg scenario, which is incredibly common when trying to scale payment technology.

Back in 2014 Google didn’t yet make their own devices. They relied on device manufacturers such as Samsung, Motorola, and even Huawei to showcase Android. Conversely, Apple had both hardware and software in-house, with almost 42% of US smartphone market share, and as iPhone users tended to have higher incomes (this is still true today). It should be no surprise that Apple was the one player that could move the market.

Apple Pay Enters the Scene (from 2014)

It wasn’t until Apple came along with Apple Pay, and a model which brought together hardware, issuers, acquirers and merchants into a new ecosystem that the true potential of NFC was realised — at least outside of Japan. From a technical perspective, owning both hardware and software allowed Apple to innovate with on-device biometrics, tokenisation, and build an effortless user experience.

As with all innovation, timing is key, and Apple got the timing right. Many large retailers were planning on updating their payment terminals by late 2015 due to a change in regulations.7

The surge in contactless capable payment terminals in the US can be seen in these statistics:

In 2014 at the time of Apple Pay’s launch only around 7% of payment terminals could accept contactless payments.

By mid-2018, 70% of payment terminals were contactless ready.

By the end of 2018 more than 95% of all payment terminals shipped were contactless capable.

In some respects Apple’s timing was fortuitous. But they built their own wave with a self-reinforcing ecosystem that consumers loved and merchants couldn’t afford to miss out on.

To quote How Apple Pay Changed Payments:

Users saw that it was fun to pay with Apple Pay, and retailers didn’t want to risk losing a sale if the cardholder couldn’t pay how they wanted to. Nothing changed overnight, but gradually, the market shifted.

In the US market the story of contactless payments became the story of Apple Pay.

Unlike FeliCa, which was only successful in Asia, Apple succeeded in making Apple Pay a global phenomenon. But success in Apple’s home market was the main factor which set the course for mobile payments to go from experimentation to exponential growth.8

Privacy has always been central to Apple’s philosophy. In the above interview from 2014 Tim Cook makes clear that Apple cannot see Apple Pay transactions.

#2.

Apple Pay Made Fintech Accessible

A few years back, after one of the COVID lockdowns my Mom was visiting me in London.

Due to the restrictions we hadn’t met for some months, and since our last meeting my Mom had got an Apple Watch.

When grabbing a couple of coffees at a Pret cafe my Mom paid with her Apple Watch!

It happened so quickly. I was surprised. I hadn’t shown her how to do this.

My Mom is from the Baby Boomer generation (born between 1946 and 1964), and the stereotype is that as we get older, our ability to use new technology worsens. As we get older we are more likely to use cash. There is some evidence to support this. A study by Age UK shows that those aged over 75 are twice as likely to have used cash for a purchase than the all-age average.

But adding cards to Apple Pay is straightforward and once set up, cards can be accessed across various devices. Using Apple Pay doesn’t require remembering a PIN, nor taking a card out of a purse or wallet. The user only has to double-tap on an iPhone or Apple Watch. It’s really easy to use.

Budgeting was often seen as one of the key benefits of cash, as you can only spend what you have in hand. Yet these days, many banks offer instant balance updates and easy-to-use apps — tracking spending is easier than ever.

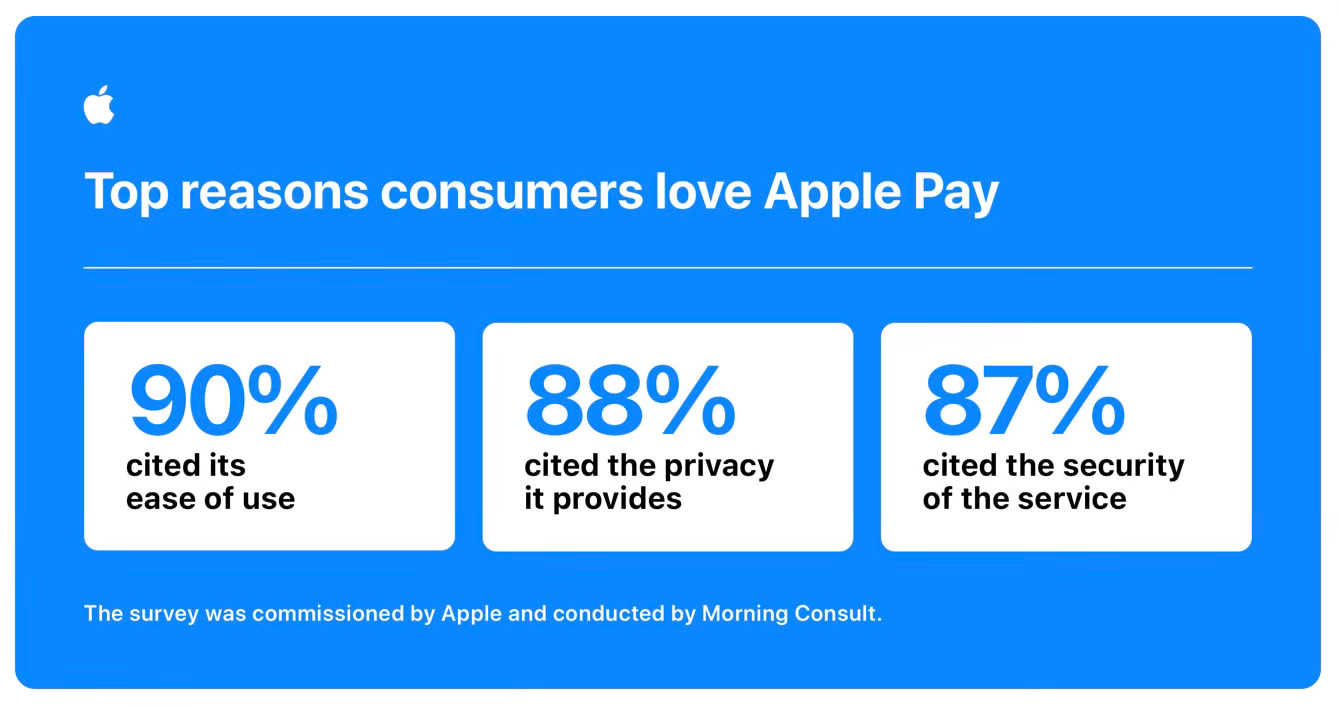

In a world where so many fintech apps claim to be “democratising” something or other, I can’t help but feel that Apple Pay is a case where fintech innovation has actually made life easier and more accessible. And while not all merchants accept Apple Pay yet, its reach continues to expand.9

#3.

Apple Pay Shows How Non-Payments Companies Can Create Substantial Revenue From Payments

Back in 2014, the Financial Times reported that Apple gets 0.15% of every Apple Pay transaction.

This comes from interchange fees that card issuers receive, not from additional charges on businesses. As you would expect, Apple has never confirmed or denied this figure as their contractual arrangements with issuing banks are confidential. Outside of the US, the margin is thought to be lower than 0.15% and a global average in the region of 0.08%-0.10% is likely.

How much revenue does Apple Pay generate for Apple? Apple Pay sits within Apple’s services business area, which is set to generate over $100 billion this year. But Apple doesn’t break out Apple Pay numbers directly. Instead, it’s captured alongside services such as iCloud and Apple Care in the overall services numbers.

However, industry analysts estimate that Apple Pay generates around $2-4 billion in annual revenue.10 These estimates are based on data from 2022 and 2023, and the reality today could be much higher. Apple Pay is likely to be more than 1% of Apple’s total revenue. In addition to transaction fees, other revenue lines that may sit within Apple Pay’s business area, such as fees from Tap to Pay on iPhone and fees associated with other adjacent product lines.

Apple has demonstrated that payments can be a multi-billion dollar business even when it’s not a company’s main focus. Apple’s primary business is selling iPhones, MacBooks, and other hardware. Although the company aims to grow services to over 30% of total revenue by 2030, for the foreseeable future Apple’s main revenue driver will remain hardware.11

Other companies with extensive distribution reach and networks on both the consumer and business sides can benefit from incorporating payments into their offering. Last year I wrote about Meta’s Payments Potential, and Google has also successfully monetised payments with Google Pay.12 Expect more companies to lean into payments to diversify revenue in the years ahead.

Note: Based on industry estimates Apple Pay could be generating more revenue than Adyen.

#4. Apple Pay Made It Easier to Travel Across Cities

Transport for London introduced the Oyster card to the Tube in 2003. This contactless smart card required users to top up credit before travel. The system worked well, and passengers could travel until their balance ran low. Traveling with an Oyster card was more efficient than buying tickets for each journey, or each day.

However, locals and tourists often formed long queues at ticket machines every morning as they sought to add money to their cards. This improved when the Tube got contactless card readers at each station in 2014. These could accept Oyster cards, but also contactless payment cards. The Tube was a great use case for contactless payments as the tap of a card opened the ticket barrier, and unlike with Oyster, there was no need to regularly top up a balance.

When Apple Pay launched in the UK in 2015 the Tube immediately supported it. The London underground provided a perfect testing ground for Apple Pay in the UK. Consumers were already familiar with contactless payment cards, and they saw the move to Apple Pay as an evolution rather than a revolution. Transport for London quickly became the largest Apple Pay merchant in the UK, and likely still is today.

In 2019 London got Express Transit functionality. Users set one payment card as their preferred transit payment option, and when traveling on the Tube no authentication — such as Face ID — is needed.13 This enhancement made getting through ticket barriers even smoother.

But it’s not just in London that Apple Pay made transit easier.

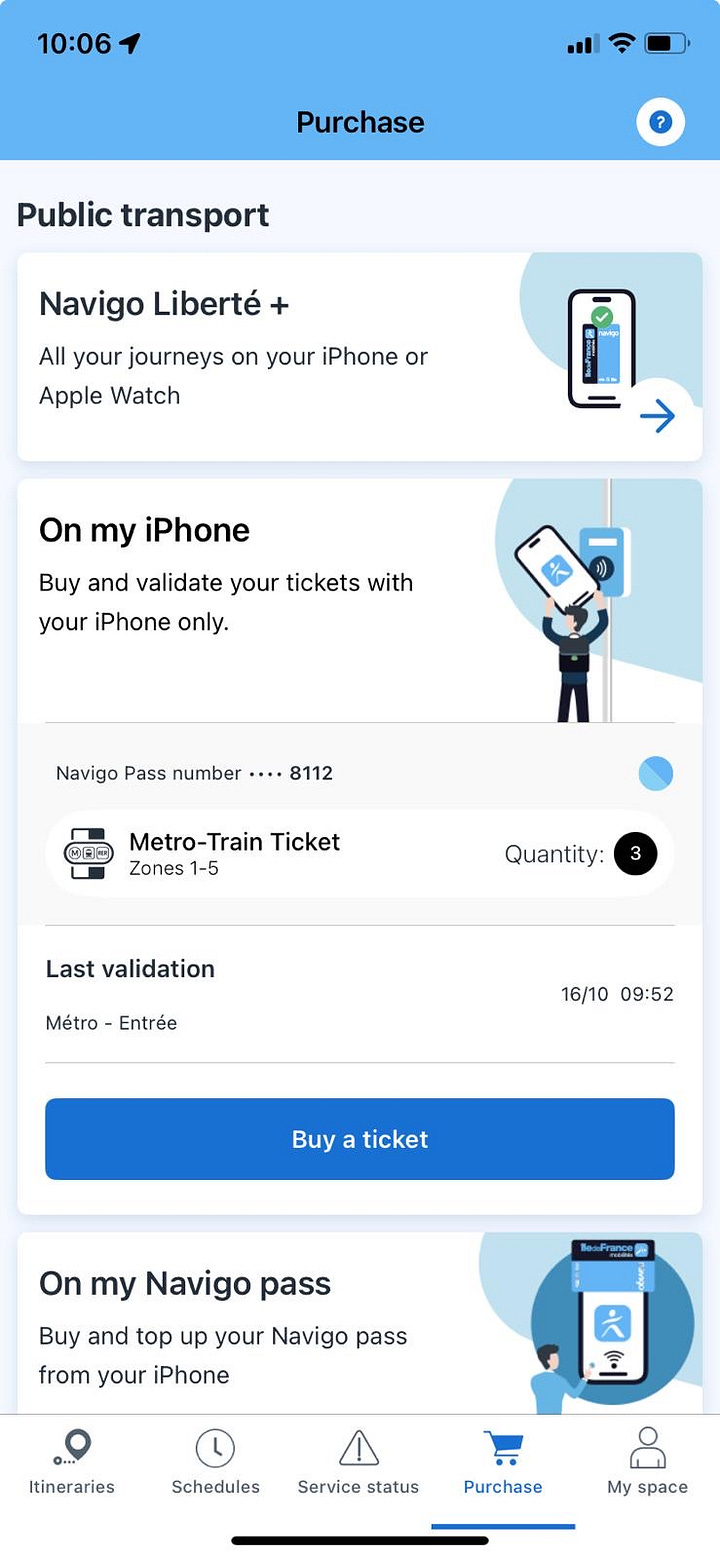

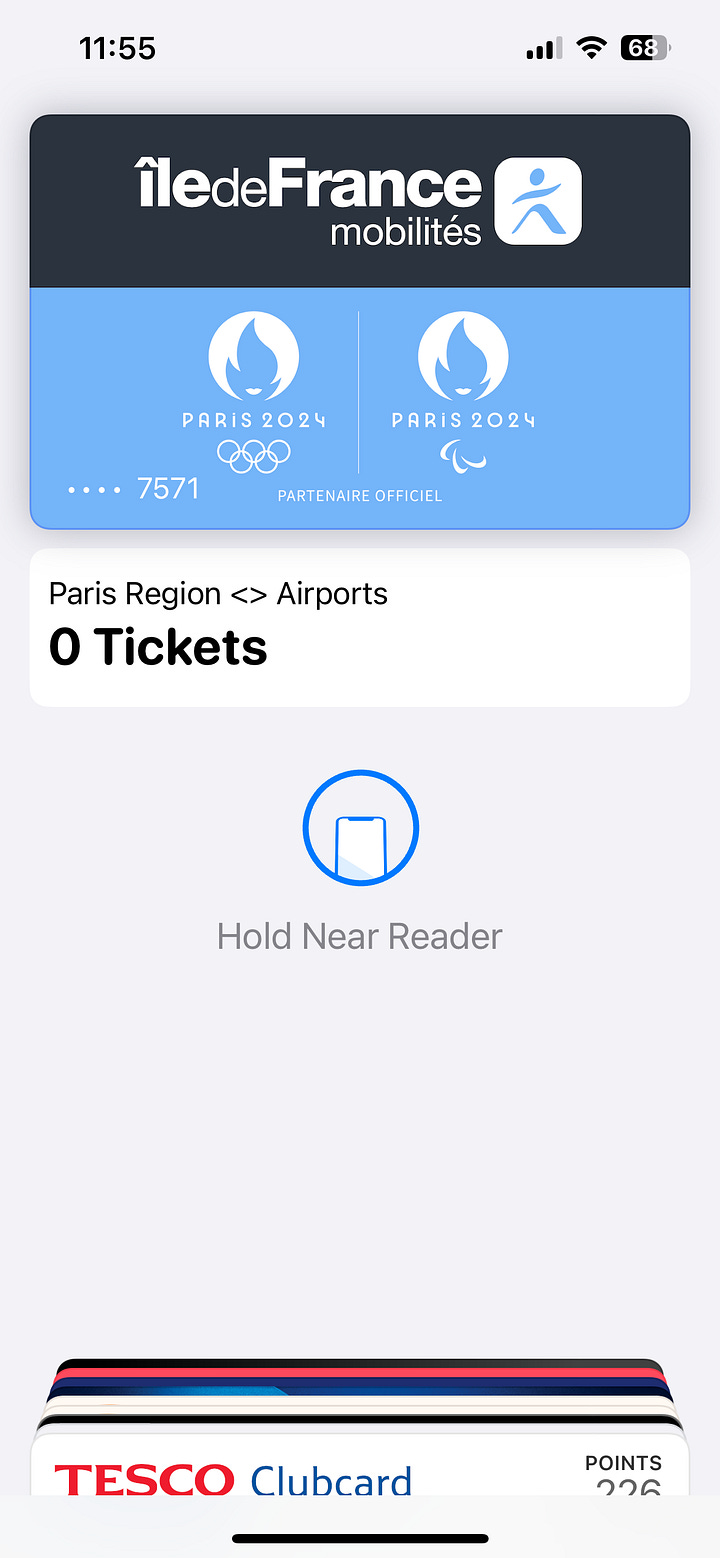

Two other examples are Paris and Tokyo. Unlike London, which operates with the tap of standard credit and debit cards, Paris and Tokyo have specific local solutions. Based on user location, Apple Pay automatically prompts users to add local transit cards to their Apple Wallet. In Paris, users can add journeys to their Apple Wallet via a local transport app using Apple Pay. In Tokyo, users add Yen to an IC card, and funds are deducted based on the journey length once completed.14

These examples show the extent to which Apple goes in order to localise its solutions to each market. It makes total sense as transit payments are high volume and high footfall. Like what happened in London, once a consumer gets used to tapping to travel on local transit they’ll be more likely to use Apple Pay in other scenarios also.

What’s striking is the user experience. Imagine arriving in Tokyo after a long flight. Rather than having to work out the ticket machines for the Metro system and get a paper ticket, you’ll get a message on your iPhone to add the local transit card to your Apple Wallet and top up in local currency. That’s all you need to do. Simple. Now you can travel.

#5.

Apple Pay Has Cemented the Bifurcation of Payments

This section is about payments and fintech, but also geopolitics, trade, and competing regional power blocs. It’s a story of the modern era that is fast-moving and ever-evolving.

This summer I spoke of the bifurcation of payments.

The idea is straightforward.

When it comes to payment technology, the world has split into two camps.

Paradigm 1

In the first camp, you’ll predominantly find Western economies such as the US, UK, EU, Australia, and New Zealand. The main cashless payment option in these countries is card payments on the Visa and Mastercard rails. Other options exist, but the preponderance of cashless transactions flows through the card rails of the major card schemes.

Paradigm 2

The second camp sits across much of Asia, Latin America, and Africa. In these markets QR code payments linked to domestic mobile wallets or direct bank payments are the norm. Not only are local payment systems cheaper, but in many cases, a local ecosystem of integrations has built up around them. In some cases local or regional superapps lead the way. (Grab is one such example.)

Cards vs QR codes

In markets that follow the first paradigm, Apple Pay is so easy to use that QR code payments feel cumbersome and clunky. Additional services such as BNPL add depth to the core payments offering, and Apple Wallet can hold loyalty cards, making the whole checkout process super easy for consumers.

Many markets operating in the second paradigm bypassed card infrastructure entirely and went straight from cash to QR-based digital wallets. For developing economies, QR codes can be the fastest and most cost-effective way to start accepting payments. There’s virtually zero cost to getting started.

Payments Sovereignty is Digital Sovereignty

As Apple Pay made card payments better, there were fewer incentives for Western governments and regulators to explore alternatives to cards. However, for some countries, developing domestic payment infrastructure outside of the purview of Visa and Mastercard is a national imperative.

Domestic payments infrastructure, controlled and regulated locally, is a form of digital sovereignty. Rightly or wrongly Visa and Mastercard may be forced to cut a market from their network due to political decisions made in the US. This drives some countries to develop local systems alongside the card networks, as a back up — as a just-in-case-we-need-it kind of thing.

We often don’t think of payments tech as geopolitical, but in today’s world, almost everything is.

The BRICS countries, which mainly sit within the second paradigm, are working on various payments initiatives, and universal innovations such as Stablecoins and Agentic Commerce have implications beyond payments alone. Cashless payments once meant card payments, but in recent times an alternative model has accelerated. In our new world, payments sovereignty, geopolitical turbulence, and fintech innovation are relentlessly intersecting.

Apple Pay didn’t create the bifurcation of payments, but the success of Apple Pay has made the card-based system even more compelling than it once was. The success of Apple Pay has cemented the bifurcation of payments.

Thanks for reading Payments Culture!

Next week in part two: Did Apple Pay kill the physical wallet? How Tap to Pay on iPhone took SoftPOS to a new level — and how virtual cards might be one of the most underrated second-order consequences of Apple Pay.

Note that views expressed on this Substack are my own and do not represent any other organisation. Also nothing I say should be taken as investment advice.

Although it didn’t scale globally, at least on a regional level FeliCa was a success.

NFC stands for Near Field Communications. It’s a wireless technology which enables the exchange of data between a payment card or a phone and a payment terminal. The technology can also be used outside of payments for instance in use cases such as ticketing at concerts and sporting events.

FeliCa still powers Hong Kong’s Octopus card, which is used for transit payments and as a prepaid mobile wallet.

In technical terms, this meant supporting NFC Type F as well as A and B.

At that time the term contactless wasn’t a commonly used term, rather the technology was often known by its contemporary Mastercard branding “PayPass”, and Visa’s equivalent branding was “PayWave.”

Of course as many readers will now know today Google Pay is on par with Apple Pay in many ways. Google has made mobile payments a success but this involved pivoting closer to the Apple Pay model and away from Google’s earlier vision of mobile payments.

The EMV mandate of October 2015 required US merchants to update their point of sale devices to accept chip cards. Prior to this, Americans usually swiped cards — quite different from the UK, which embraced what became known as “chip and PIN” much earlier. Retailers who didn’t update became liable for fraud losses, so widespread terminal upgrades followed. These updates often included contactless acceptance capabilities, allowing tap to pay cards as well as Apple Pay.

Data from Capital One indicates that as of June 2025, 41.5% of companies that accept Apple Pay are based in the United States. This statistic highlights that still today the US market is absolute key to the success of Apple Pay.

Various parties are working to increase card acceptance at small businesses worldwide. Visa and Mastercard have programmes at a local level to get businesses to start accepting cards. Payments processors and banks are pro-actively targeting small businesses via products such as Tap to Pay on iPhone. There’s a long tail of small businesses who are starting to take cards for the first time and demand for mobile payments is helping with this.

The main source of this information is Capital One’s Apple Pay Statistics which are updated regularly.

The Financial Times recently reported that by the end of the decade the total revenue from the services business unit could hit $175 billion per annum.

Data on Google Pay is hard to come by, making direct comparison with Apple Pay challenging, especially since Google Pay’s offering differs and is fragmented across markets.

Although I’m certain that many people don’t know that the Express Transit mode exists. Every day I see people clumsily using FaceID before tapping their phone on the ticket gate on the Tube, seemingly unaware they don’t need to do this when traveling.

The Tokyo Subway looks completed. For tourists, using Apple Pay can make traveling across the city at that little bit easier. It takes care of the payment part at least.

Great article Matt! Many people don't realise the extent (and impact) of Apple'e influence on payment innovation.

Interesting read on Apple Pay!

Apple will evolve.. It will have to start acting like a savvy allocator and take decisions accordingly because sitting on $250B+ of cash ~ and what is the biggest market out there ~ payments! $200Trillion.