Three fintech stories for the weekend (#1)

Monzo and Nubank eye the US; Stripe's reading obsession; Is BNPL driving a new debt culture?

Welcome to Payments Culture!

This newsletter explores how money moves, around the world. In this weekend edition I cover three fintech stories that have caught my eye in the past week.

I’m currently looking for new opportunities. I’m open to short-term assignments as well as permanent positions. You can email me or contact me on LinkedIn to discuss further.

Monzo and Nubank eye the US

Breaking into the US is the dream for many European fintechs. As many find out, it’s arduous work, and some spend millions of dollars only to walk away as they can’t make it work. (N26 tried to crack the US market for two-and-a-half years but then gave up.)

At a recent industry event, I heard Tom Oldham, Group CFO of Monzo, discuss the UK-based neobank’s international expansion plans. He mentioned that, for Monzo, US expansion is still very much a work in progress, but there was no commitment on any next steps.

In fact Monzo is live in the US, and has been for a number of years with Sutton Bank and Lead Bank as local partners, but marketing has been almost non-existent. You can say that they’re live, yet they haven’t properly launched. There’s been no marketing push, and the Product Market Fit (PMF) that Monzo wants to get right before pushing into the US market at scale is still evolving.

The Financial Times reported this week that Monzo is getting more serious about US expansion, and is seeking a US banking licence:

Monzo is considering a new application for a US banking licence four years after backing out of a previous attempt when it reached an impasse with regulators... Both the OCC and the other US bank regulator, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, have rescinded guidance that had made deals harder to complete.

A US banking license would allow Monzo to operate without its partner banks. This means owning more of the infrastructure and capturing more of the revenue. Monzo’s last attempt to get a full banking license stalled due to the regulatory environment. However under the Trump administration Regulatory guidance has since changed, so this second push may prove to be more fruitful.

There is a belief inside Monzo that what they offer is genuinely different: a unique user experience and a customer engagement model unlike anything else seen in the US so far. Their evidence backs up their ambitions. Consider what Monzo has achieved recently in the UK:

Monzo won the Marketing Society Brand of the Year 2024, becoming the first fintech or bank to win the prestigious award.

Monzo has been consistently launching new product innovations. One which has gone under the radar, but is extremely valuable for users, is the ability to undo a payment. An outgoing bank transfer can be reversed within up to one minute of sending. Very useful when research shows that 1 in 10 UK users have accidentally sent money to the wrong person.

If we go back ten years, Monzo’s customer base mainly used the bank as a secondary account — adding a few hundred pounds here and there to take advantage of the FX-free debit card when travelling. However, many newer customers of Monzo use the bank as their primary account from the get go. An estimated 30-40% of Monzo users now utilise the bank as their main account.

Monzo’s US strategy will be to take what has worked so well for them in the UK, yet localise and find the right PMF for the US market. This is no mean feat. Many have tried and failed. Success means understanding what US consumers expect from a bank while at the same time innovating to draw users in.

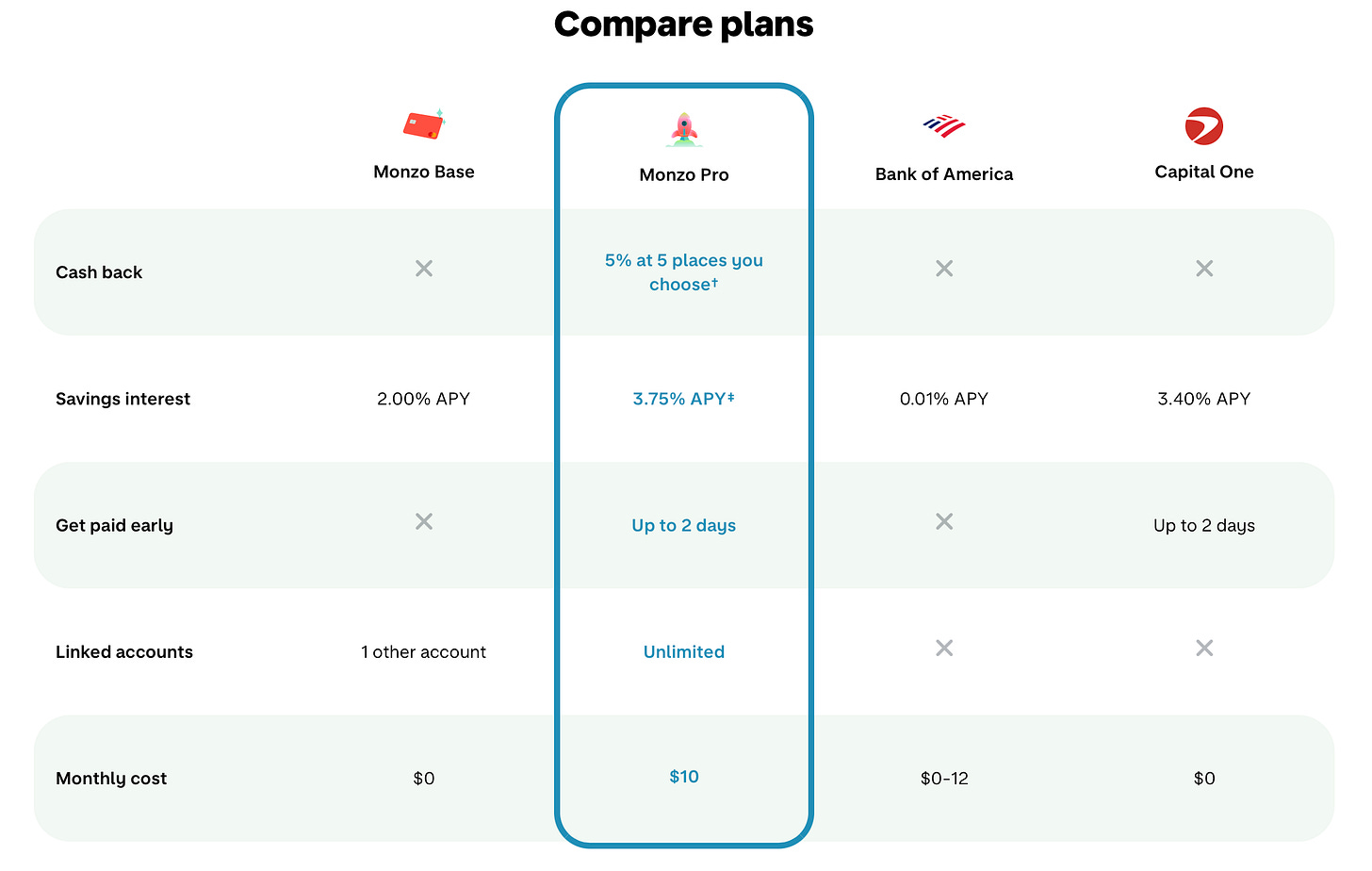

The graphic below chat Monzo’s basic US account, its pro account, and accounts from Bank of America and Capital One.

In the US certain things are expected as standard when launching a bank. For instance, Monzo offers FDIC-insured accounts via its partner banks. Whereas in the UK, Monzo’s had no deposit insurance for the first two years, and this was only present once they obtained their full banking license.

Low interchange rates mean that rewards are sparse on debit cards in the UK. In the US interchange is higher. Juicy rewards are the norm. Monzo’s pro account offers 5% cashback with selected merchants, however, it’s only available in two states at this time (Minnesota and Florida). What this illustrates is that Monzo’s US strategy is an iterative one. They are still testing and learning, figuring out what works and doesn’t, and fine-tuning their business model.

This focused approach isn’t new to Monzo, it’s how they started in the UK too. For the first few years of operating Monzo was a London-centric company. This was intentional as a way of staying close to early adopters in a very practical sense. Most users were in London, and the trademark hot coral cards were seen more in the bars of Shoreditch than the pubs of Liverpool.

As well as Monzo, another major neobank made the news this week with their US expansion plans. Nubank has over 110 million customers across Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico, and plans to enter the US market via a national banking charter.

Incidentally, there’s an interesting connection between these two US expansion stories. Monzo’s Group CFO Tom Oldham previously worked in a senior position at Nubank. Though unlike Monzo, Nubank is not looking to work with partner banks as a way to get started more quickly. Instead they plan to wait until they get full banking license approval before launching. They’ve already unveiled their US board of directors, which includes Roberto Campos Neto, former President of the Central Bank of Brazil.

Stripe’s reading obsession

Stripe has always been more than a payments company. Back in 2017, co-founder Patrick Collison told Kara Swisher that:

We’ve always viewed Stripe as a multi-decade undertaking. We measure our progress, we talk about this idea of increasing the GDP of the internet, and we measure our progress on that basis.

Patrick’s comment that Stripe is a multi-decade undertaking is notable, especially when we consider that many of Stripe’s competitors — particularly publicly listed companies — operate on a quarter-by-quarter basis (to meet shareholder expectations). I’ve rarely heard other CEOs talk in terms of decades. This can only happen in a founder-led organisation.

Stripe has a book publishing arm called Stripe Press that publishes books related to technological, economic, and scientific advancement. The remit runs quite broad, with books on the classic computer game Prince of Persia, a recent history of AI from Dwarkesh Patel, and a how to guide “Scaling People” from Stripe’s former COO Claire Hughes.

Stripe Press isn’t going to move the needle when it comes to revenue. But the books are gorgeous and look so great that it’d be easy to collect them all, even if you don’t want to read them. The reality is that the Collison brothers have always loved books, and reading shaped their thinking from an early age.

Thomas Yeddou is a ghostwriter for fintech CEOs, and he recently wrote about how books shaped the Collison brothers. He noted that reading was a daily ritual for Patrick and John Collison. Growing up in a small village in Ireland, reading books was a window to the wider world. This voracious reading habit led to their passion for computers, programming, and entrepreneurship.

The brothers’ love of reading shaped Stripe in many ways, as Thomas notes:

That reverence for reading translated into a distinctive writing culture inside Stripe. The brothers insisted on long-form memos and carefully argued proposals. “The first emails I saw from our CEO literally had footnotes,” recalled a former Head of Docs at Stripe in a blog post. “He structured his emails to be like research papers and put the peripheral information at the bottom so as not to detract from the core information.”

Rather than creating lengthy sequences of PowerPoint slides, in Stripe, managers are expected to express opinions in written form. The what and why of requests and decisions should be transparent and well-reasoned. Information is circulated widely, so team members can understand the thought process behind what’s been agreed.

Reading, thinking, and writing all go together in Stripe’s culture.

Further reading: Patrick Collison’s reading list on his personal homepage

Further reading: Ten reading suggestions from Thomas Yeddou

Is BNPL driving a new debt culture?

These days you can Klarna everything from burritos to Coachella tickets. Klarna was initially used for specific use cases — why not buy four t-shirts knowing you’ll send two or three of them back? Because you’ll only pay for what you keep and won’t get charged for all of them upfront. But as I noted in a previous post, BNPL has evolved since its early days, and now nothing is off limits.

A long read in the New York Times Magazine this weekend by Amy X. Wang explores how BNPL has trapped users in a “vortex of debt”. I love this writing style, which brings fintech into the real world, mixing stats and info with actual examples of how payment tech has helped or harmed users in the real world. The article profiles Elysia Berman, who experienced payments cascading across various BNPL purchases:

Each day, Berman woke up to notifications on her phone, announcing how much money was being automatically siphoned out of her bank account. The amounts seemed totally arbitrary — $17 first thing Monday, $250 later that night, $141 Tuesday — with no explanation of what items she was even paying for. She would learn $600 was leaving her account to Sephora or Saks, but she had a hard time finding any easy-to-read tallies of balances on the B.N.P.L. apps.

Many small purchases can soon add up leading to balances in the tens of thousands across different BNPL providers. There’s not just Klarna, but other providers such as Affirm, PayPal, Sezzle, and Zip.

One stat from the article is mind-blowing: BNPL was worth “$120 billion in 2023 in the United States, up from just $2 billion in 2019”, and while Berman had a credit card limit of $2,000, Klarna gave her $12,000 to spend. On one hand, the promise of BNPL is short-term credit at the point of sale for a specific purchase (in some cases, BNPL apps will tell you the maximum amount they will lend). This differs from getting a credit card with a set total limit in advance of shopping . Yet the BNPL model which provisions credit for each purchase, can lead to fragmentation as various providers, by default, collect payments for each purchase individually.

Regulation is tightening and in the US some BNPL providers will soon integrate credit scores into their decisioning, but it’s not mandatory. This is one big gap between BNPL and traditional credit. When a user applies for a credit card, lenders can see the outstanding balances across other providers in their credit history, whereas this isn’t the case for BNPL so far.

What I liked about the article was how it anchored a story about payments in the real world, and highlighted how BNPL has provided an artificial lifestyle boost to consumers who don’t feel they are taking on debt. It’s a couple of clicks or taps at checkout and BNPL providers do everything possible to make conversion from online shopping to payment as easy as possible.

BNPL isn’t going anywhere — consumers like the product. The momentum is such that banks like Citi, Chase, along with American Express, now offer products that resemble BNPL. These products typically split payments into equal instalments. Yet the story of BNPL is one that highlights how regulation needs to keep up and adapt. It shouldn’t be possible for consumers to ratchet up way more debt with BNPL than would be possible on a credit card.

It’s an irony that BNPL was supposed to make it easier to take on short-term debt at low risk, yet in this case, it led to much larger long-term debt, with Berman losing track of her various payments. Such cases suggest the BNPL model needs refinement. Do consumers need better tools to track how debt across multiple providers racks up?

Thanks for reading Payments Culture!

Please leave a comment or share with a friend if you enjoyed reading this edition. It’s much appreciated and helps grow the audience of this newsletter.

Note that views expressed on this Substack are my own and do not represent any other organisation. Also nothing I say should be taken as investment advice.

Thank you for sharing my piece Matt!